“No matter what I tried, what fit best was work that involved my love of something small-scale and intimate.”

Richard Baker, “Cascade” (2008), oil on canvas, 25 x 20 inches (all images courtesy Tibor de Nagy Gallery unless otherwise noted)

For many years, during the off-season, Baker used the studio at artist Pat de Groot’s house in Provincetown, and I would see his paintings lining the staircase wall, where she kept her collection of friends’ work. Baker later used a studio at my friend Sarah Lutz’s house in Truro, and he exhibits with Albert Merola Gallery in Provincetown. These traces of his presence assumed significance for me.

Richard Baker (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

But here in Truro, a beautiful, sparely decorated old farm building in the evening quietude, was a fitting backdrop. Baker’s work can be about letting time — and the pretensions of art world — drop away, as we turn to the ordinary.

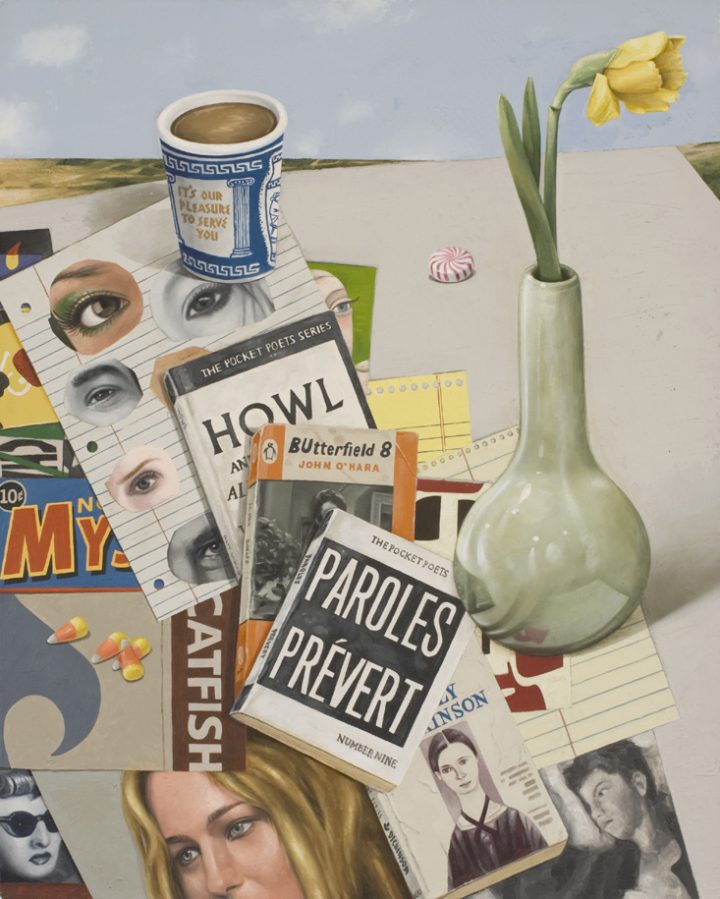

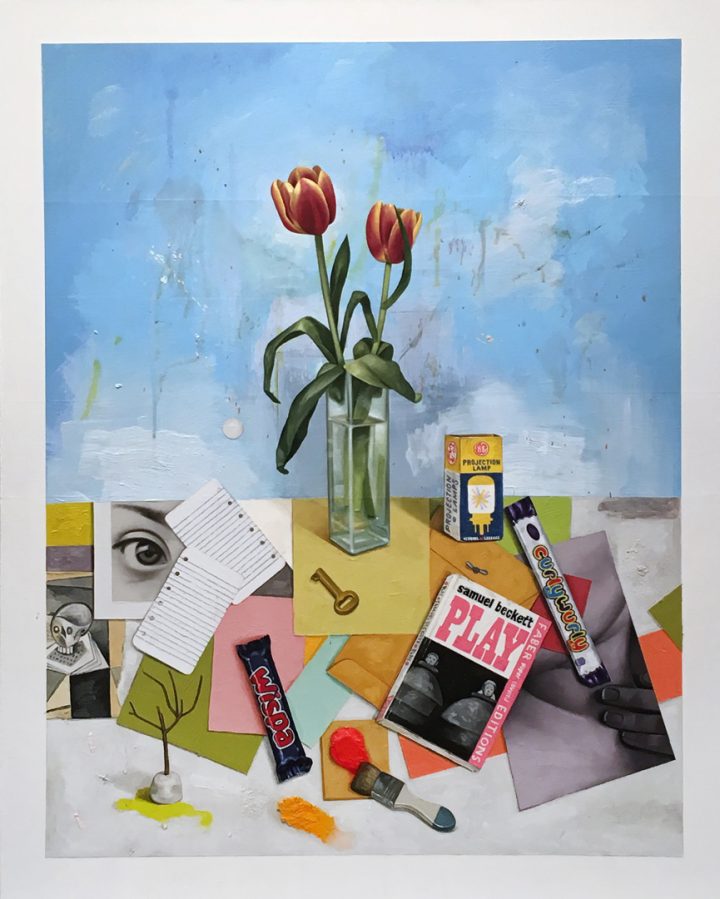

Baker has made oil paintings of tabletops tilted upwards to show the clutter and strange collage of everyday matter: mints, coffee cups, books, photographs, notepaper, and flowers.

His gouache paintings on paper have taken us along on obsessive bibliophile journeys: multiple editions of the same book, New York School poetry, familiar classics, and vintage psychotherapy books, among many others.

He will often turn his attention to a single object, or a pair of things that don’t really go together, like a paper price tag and a vase of tulips. The surfaces of the paintings are markers of Baker’s dedicated attention to the ordinary and the esoteric: they are as touched as the objects he renders. Although the paintings often have a poetic strangeness and mystery, they are also very playful. He paints bags of flour and cereal boxes, and he’s made trompe-l’oeil sculptural objects of a package of Chuckles and toasted marshmallows on a stick.

Baker was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1959. He studied at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore followed by the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. He is represented in New York by Tibor de Nagy Gallery, where an exhibition of his work from the 1980s and 1990s is on view through October 6.

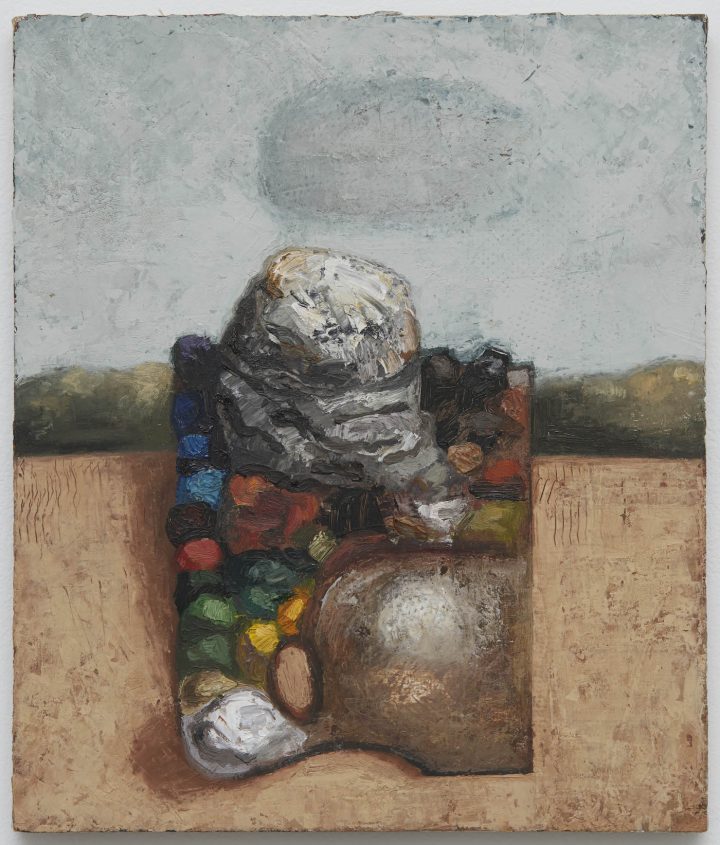

Richard Baker, “Palette” (1990), oil on linen, 13 x 11 inches

Richard Baker: I started drawing in the high school cafeteria to deflect bullies. If I drew caricatures of other people, the danger of attention could be turned away from me. It was mean, but it worked; it was self-protective. From doing that, I developed a real interest.

The only art classes I took were in public schools, but I found the art room could be a sanctuary from the rest of the world. Until I left high school, I had no real education in art. I knew of Picasso, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Dalí, and Escher. Beyond that, there was no real access to what art was.

My family in Baltimore was a working-class, steel-working family. My parents were Depression-era kids with elementary school educations. They were supportive, valued education, and had the attitude that their children should do better than they did.

The first show announcement that I sent to my mother, the first thing she said was, “That would make a lovely Hallmark card.” Instead of being injured by that, it was like, “Yes!” because if my family could get it on some level, and someone else could get the more “sophisticated” level, then what more could I want? It is two ways into something, and that always appealed to me. There’s humor in that.

Richard Baker, “Untitled (Flower)” (1989), oil on wood, 10 x 8 inches

RB: I really appreciate it in hindsight. I loved how the studio practice and academics were connected. What art school makes you take a physics class? It was mind-boggling and required.

But after two years, I felt that I had to leave my hometown. I moved to Boston because my older brother lived there. He was draft-dodging member of the Youth International Party. He had established himself under an assumed identity and was raising a family and was getting tired of being undercover. He was 12 years older than me, and had left our house when I was six, so he became kind of a figment of my imagination. I wanted to get to know him, so I moved to Boston. It led to the rest of my life; it cracked things open.

In Boston I tried the Museum School, which was also a misfit. It was highly competitive and abstract painting was dominant, although there were other pockets of things; for instance, Nan Goldin and Jack Pierson were there at the time. The years that I spent at MICA and the Museum School weren’t the right time for the art I wanted to do. It was that strange lag time after Abstract Expressionism, which influenced the teaching style. But the large-scale, bombastic paintings of the up-and-coming 1980s Neo Expressionism also didn’t fit. It felt oppressive.

Richard Baker, “Debris” (1998), oil on wood, 20 x 19 5/8 inches

RB: No matter what I tried, what fit best was work that involved my love of something small-scale and intimate. I was enamored with Chardin and Morandi. I was interested in something that was modest, and not theatrical. The tension between what was dominant in the culture ultimately caused me to give up painting for a while, after I left school. It felt like an eternity.

JS:What made you go back to painting?

RB: There was an iris sitting in a bottle on my table in Cambridge, where I had moved. I decided that all I wanted to do was find a way to render what my eye was seeing through my hand: no composition, no art pretense. It was just about how to make things in front of me appear on this two-dimensional surface, with my hand, and not disguise them as photo-realist. It was about a one-to-one correspondence, connected in the material. I sat down and did it. I made a very small painting, about 3 inches square on wood, of a single iris in a color field.

That got me hooked again. I realized I could paint something that I was experiencing, and that was simple and commonplace. We all apprehend things in our daily life that we derive pleasure and beauty from, and which we don’t spend a lot of time thinking about. I started doing little icons of those kinds of moments. They were paintings based on observing something carefully, but not about careful rendering. They were also about the joy of oil paint and the joy of the materials. They were natural forms suspended in a color field. It was out of step with the time, as far as I knew. I would see people doing it, but they weren’t public figures. They were all beneath the public radar: artist’s artists.

Richard Baker, “Lunch #3” (1990), oil on linen over canvas, 9 x 8 inches

RB: I had been living in Boston, and had a loft on Summer Street when it was all illegal living there. My girlfriend was offered a job at a retail clothing store. I had never been to the Cape before. The first couple years I went back to Boston for the winters. After that I decided to move there year-round.

I realized I could make a life for myself there. If I worked like a madman for four months of the year, I would accrue an unemployment account. I was able to draw from it during the winter. I could live on the Cape rent-free in the winter, because the summertime residents needed young people to watch their houses. The days were endless: walking on the back shore, and painting in the studio.

JS:What led you to your longstanding series of gouache paintings of book covers?

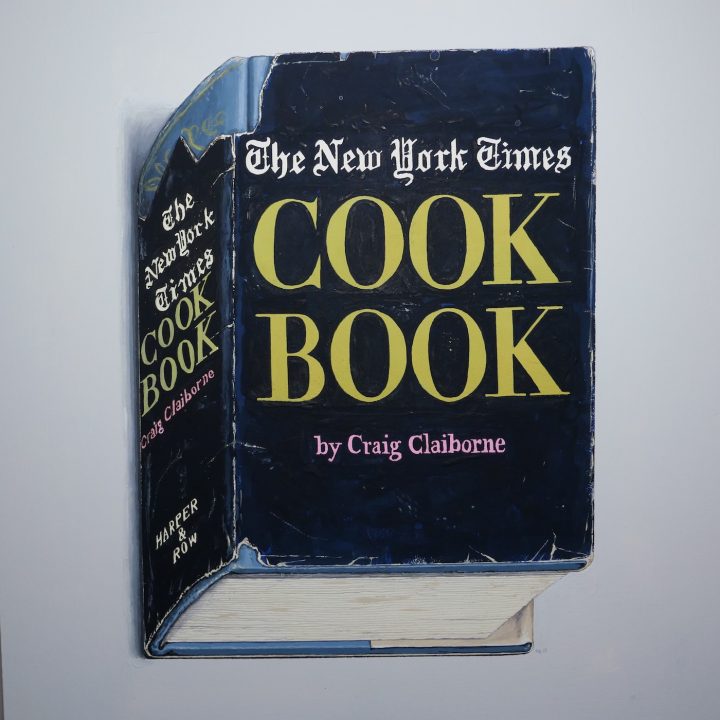

RB: The gouache paintings were designed to be, for lack of a better word, “boilerplate.” I wanted to jettison all of the art concerns: composition, scale. I wanted the representation to be the same size as the book itself, to retain that intimate connection that you have with the object. They were about assembling ideas that flowed between the selection of things.

Richard Baker, “New York Times Cookbook – Craig Claiborne” (2019), gouache and watercolor on board, 14 x 16 inches

RB: People bring me books and they commission paintings of books, and so I become involved in people’s lives. I’m involved in that social fabric, which is beautiful. It might be their husband’s favorite book, or they might remember the circumstances of reading something. The associations are built into that object.

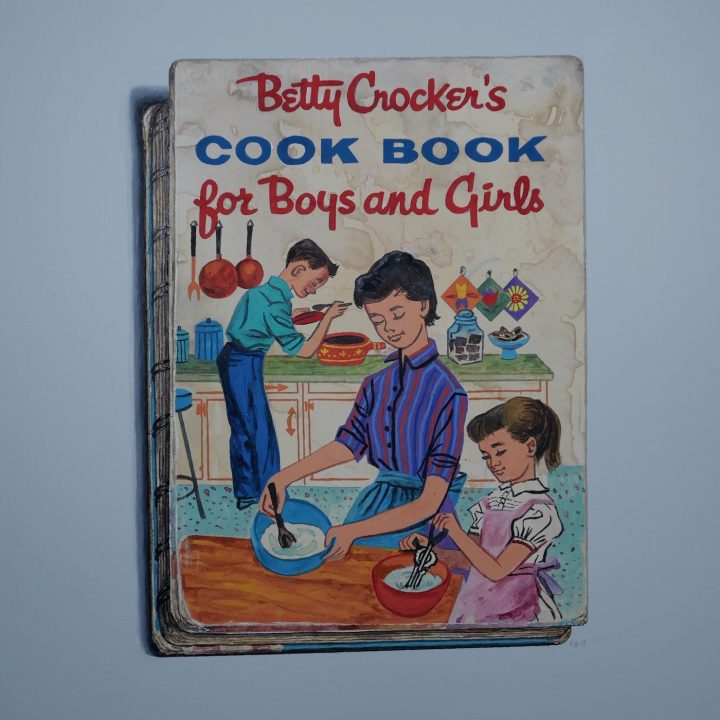

JS:You’ve been working on a series of cookbooks. What interests you about the cookbooks?

RB: Cookbooks contain the idea of domesticity and comfort. They are familiar and associated with sociability. I like to make paintings of things that aren’t considered major subjects: things that are castaway, or debris. I like turning the lens onto what our lives are really like: putting one foot in front of the other.

JS:I’ve noticed that you use the word “portraits” to describe the paintings of books. Why do you call them portraits?

RB: I have used the word “portrait” from the beginning. I started painting portraits of books in 2004. At first it was because I wanted to get rid of specific books that I had been carrying around for five or ten years. It was a specific edition, and I was painting the rips, the stains, and the markings that made up the personality of that book. They were not Pop Art, and they were not overtly about design. They were about the object and the history it contained. It’s like us: we walk around making clothing choices, we bear the abuse of the sun on our skin. We get pimples, we cut ourselves shaving. We carry around that history on our exterior, like the books.

Richard Baker, “Betty Crocker” (2019), gouache and watercolor on paper, 12 x 10 ½ inches

RB: Yes, I like to cover the ground high-brow and low-brow. There’s an assumption that the paintings are surrealist but they are much more a stupid joke with myself. I thought about placing objects in color fields, and that led to considering the word play of “color / field.” What if the “field” were a field in a landscape, and you put into it a flounder painted in a certain color?

Then I thought about how color fields are versatile and don’t need to be oriented in a certain direction. I let the landscape crawl around the edges of the painting. I would end up with an object in the center and four landscapes at the edges. I thought, “Four paintings in one. It’s a bargain for whoever buys that one!”

All the objects I’ve made, like the Whoopee Cushions, come out of that. How dumb can you be and get away with it? I have no skills in sculpture, so I was thinking, “What is the easiest way to make a sculpture?” You could take a dowel and put it through a pencil sharpener and paint it like a pencil. Boom, you’ve got a sculpture.

I have a whole collection of paper bricks at home. You pick them up and they are as light as air but they look like bricks. You want to say, “Please touch the art” – because you won’t get it otherwise. Those came out of Krazy Kat. Krazy Kat was in love with Ignatz the mouse and Ignatz hated Krazy Kat. Ignatz would hit the cat with the brick and hearts would go off — love. I gave my therapist one of these “Love” sculptures that are a hollow paper core with an object inside. I said, “When you have a patient with love problems, just give them the brick and ask them to rattle it.” It makes a sound and that’s the “love” in the heart of the brick.

Richard Baker, “Party Favor” (2013), gouache on paper

RB: Well that’s the high-brow, low-brow thing. There are the chin-strokers saying, “Hmmm…” and there are the people who laugh. It’s not up to me after I make it. But what does it say about you?

This is one of the appeals of trompe l’oeil. It’s kind of stupid, like “Haha, fooled you!” but it’s very sophisticated in certain painter’s hands. I like the artists who are less skillful in fooling the eye. It’s the difference between William Harnett and John F. Peto. Harnett is very skillful in making you think “Can I open that latch?” Peto is kind of clunky, because he loves the paint and the material. It’s like going on the Cyclone instead of the King’s Dominion roller coaster. You’re going to have the same ride, but the Cyclone can really be scary, because you’re on this rickety wood thing. You’re not so scared on the King’s Dominion because it’s made of tubular steel.

JS:I saw a painting of yours from 1980 at the Provincetown Museum which shows a flounder, which is sort of floating at the center, along with smokestacks at the bottom edge. Can you talk about the combination of two distinct elements in the work? You are showing early work at Tibor de Nagy Gallery. How does it feel looking back at this work?

RB: Yes, they are hybrid landscapes that integrate Baltimore and Cape Cod. The smoke stacks are a reference to my Baltimore past. I’ve recently moved to Cambridge after living in New York for about 25 years, where I had been in the same studio for over 20 years — a hoarder’s delight. I had 55 cartons of books. But I forgot that I had all the work that I’m showing at Tibor. I pulled out one painting after another, and realized there was enough to show a time stamp of a period. They are all small-scale pieces.

The impulses are all the same: where the work gets conceived from. But I think the sense of touch has changed. When I look back on the younger work there is a direct connection of one mark equaling one set of observational moments. I think that has become diffused because I’ve had to divide my attention and responsibilities out of the studio. I want to go back and revisit those themes, revisit that scale, and see not what might make a fish painting different from what it was 30 years ago.

Richard Baker, “Flatfish” (1990), oil on panel, 16 x 16 inches

Making life happen on a daily basis in New York is much more distracting than making life happen beachside. It diluted my ability to concentrate in an uninterrupted way and maintain the direct connection between subject matter and making. When you aren’t fighting against the distractions, time disappears in a beautiful way.

JS:I know the oil paintings of still lifes involve a very different process from the gouache paintings. How does this work evolve?

RB: The oil paintings start out as abstractions. I’ll put paint and textures on the canvas. Things that happen on the canvas recall other experiences in my life. I never set up the still life arrangements fully. It’s always an accumulation of impulses that find each other. I feel like a conduit more than a director.

For years, I’ve kept card boxes full of images. When I go through a magazine or newspaper and there’s an image that attracts me, I immediately cut it out. I try not to analyze what attracted me to it. I paste it on a card and put it in the box. Then, I’ll go through the box occasionally and maybe I will find a sequence of similar images, like a hanging bare light bulb. So, if a drip of paint in the abstract beginnings becomes a vertical thing of a certain length, I might think of a light bulb. The abstract field generates associations, and these go back to other associations that have been catalogued. The two things come together and connect and start to form the image.

Richard Baker, “April” (2016), oil on canvas, 40 x 32 inches

I don’t like the idea of chronology, of one thing following another. The cards can be shuffled around. Even in sketch books, I started using hole-punched sheets, so that I could keep reshuffling the deck. The book paintings also collapse time in a way that interests me. I remember my high school self that read that Henry Miller novel. I’m not the same person I am now, but I connect to that time, and the person that I was.

It has to do with being at the center of our own experience, which we all are. You stand looking in the mirror as an adolescent, and you stand looking at yourself today. You’re not exactly the same person, but you’re in the same position. The work is all about trying to relocate me in that position that occupies every moment – yesterday, today, tomorrow.