By Julia Reed via Garden & Gun

How Dallas artist David Bates shook free of convention and rose to the top of the country’s art scene

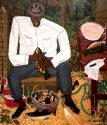

In 1982, when David Bates painted the monumental Ed Walker Cleaning Fish, he still made his living teaching art history at Southern Methodist University, where he’d gotten both his undergraduate degree and his MFA. The “little red house” in which he and his wife, the painter Jan Lee Bates, lived at the time, had walls so small he jokes that one could have made a nice easel for the 84-by-72-inch portrait. “I never really counted on making a living doing this,” Bates says, adding that it was the teaching salary that freed him up to make pictures of subjects that spoke to him. “That’s why I could paint an old black guy cleaning fish with a bucket of fish guts at his feet. Because I never thought anybody was going to buy something like that.”

As it happens, Ed Walker and his bucket of guts is now owned by the Dallas Museum of Art. Most recently, it was given star status in a recent retrospective of Bates’s work, mounted simultaneously at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. The enormous joint shows, which ran from February through early May of this year, spanned the artist’s forty-plus-year career and featured more than 110 paintings, drawings, and sculptures. Included were plenty more fishing scenes (The Cleaning Table, Bait Fish, Stringer of Sheepshead), flora and fauna (irises and magnolias, egrets and snakes), portraits (of himself, of Jan, of deeply affecting Hurricane Katrina survivors), and sculpture ranging from the charming Beer and Cigarettes to masterly reclining nudes and macho bronze sunflowers.

While the works’ subject matter has remained close to the artist’s heart and home, their appeal extends a whole lot further afield. Among the institutions that lent works to the retrospective are the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Yale University Art Gallery, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. “His masterful technique creates an unforgettable portrait of a particular place and its inhabitants,” says Marla Price, the Modern’s director, who mounted her first Bates show in 1988 just after she arrived at the Fort Worth museum from the National Gallery of Art. But, Price adds, “he translates his own experiences into works of art that transcend regional boundaries.”

When the shows opened in February, D magazine ran a profile of Bates titled “The Most Successful Dallas Artist Ever.” But that success is all the more remarkable for the fact that he has achieved it on his own terms, and—unlike such Texas expats as Robert Rauschenberg, John Alexander, and Julian Schnabel—without ever really leaving his hometown.

Bates was born in 1952 in the Dallas suburb of Garland. His father was a traveling salesman who, early on, imbued his only son with a passion for fishing and the outdoors. His mother, who had studied illustration at the Art Institute of Chicago, took him to art classes at the Dallas Museum of Art and had her own passion for flower arranging. “She would make these really wild arrangements,” Bates says, “very minimalist and Japanese.” His mother’s influence is found in his exuberant flower still lifes, while his father is oft suggested in his many portraits of fishermen. When the young David was allowed to choose the locale of the family’s summer vacation, it was almost always Galveston, the community on the Texas Gulf Coast that would later inspire an entire period of his paintings.

In 1976, while still studying at SMU—and on the advice of Schnabel—he applied for a spot in the independent study program at Manhattan’s Whitney Museum of American Art (his future wife Jan’s work had already been shown the year before, in the museum’s prestigious biennial). “I went up there intent on painting,” he says, “but they said, ‘No, man, that’s for dead people.’” He made videos instead—“reel-to-reel in those days.” His classmates included feminist conceptual artist Jenny Holzer. Though he was definitely the only one of the bunch with a Texas accent and deckhand’s wardrobe (he says the others teased him that had he come up for an interview, he’d never have been accepted), he earned enough respect to be encouraged to stay. Performance artists Sylvia and Robert Whitman went so far as to offer him a place to live. But, Bates says, with typical, almost merry understatement, “it wasn’t my deal.”

His deal, instead, was to hold fast to the idea that art need not be trendy to be interesting or good—a concept that is still met with some skepticism. “In fashionable art-world circles the paintings of David Bates are considered conservative if not reactionary or, at best, guilty pleasures, if they are considered at all,” wrote the New York Times’s co–chief art critic, Roberta Smith, as late as 2006, in a review of a show at Manhattan’s DC Moore Gallery. “If I wanted to signal my agreement I would say that I like them against my better judgment, but in truth I just like them.”

Exuberant, empathetic, created by someone in utter control of his medium, they are impossible not to like, perhaps also because the painter (and sculptor) himself is so clearly invested in and enlivened by his subject matter. When Bates left New York, he returned to the people and places that mattered to him most—which by then included Jan, whom he married in 1978. Jan introduced him to the pleasures of country music (she had been an extra in Robert Altman’s Nashville) and folk art (together they began to collect). Then, in 1982, there was another introduction, this time to Grassy Lake, the place that would become the artist’s spiritual home and floating studio, and which would lead to his first great success.

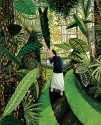

Bates first went to Grassy (to use the artist’s own shorthand), a private hunting camp and nature preserve near Texarkana, Arkansas, with his close friend the Dallas collector Claude Albritton, who owns the city’s McKinney Avenue Contemporary. The plan had been to go fishing, but Bates was struck by the eerie light and abundant wildlife of the swamp, which is a breeding ground for egrets, ibis, and herons, as well as a migratory stop for ducks and geese. There were also frogs and snakes and gators, of course, and a density that surpasses the more spread-out Everglades. “It was like a dream, a place of strange beauty and complex compositions that changes completely from sunrise to noon,” he told art historian Justin Spring. “I knew I had found something I couldn’t learn in school or from other art and artists.” Though he does admit to being inspired by the Audubons hanging in Albritton’s cabin. Bates’s Night Heron is an homage of sorts: “You think of all the artists who have done that—he’s the best,” Bates says.

On repeat trips over the next decade, he immersed himself in the daily life there, sketching feverishly in small notepads (his version of a camera—think Gauguin in Tahiti), which he would later translate into huge oils, including Ed Walker, one of the first three Grassy works. The distance between sketch and paint, he says, enabled him to “render complex information” and to organize it, but also to be “somewhat spontaneous.” By the end of 1984, he had stopped teaching and found his métier. Lynda Hartigan, the former chief curator at the Smithsonian who is now at the Peabody Essex, has cited the “finely tuned tension between specificity and mystery” in the Grassy Lake works, “the products of an abundance of detail on the one hand and a palpable sense of awe, even transport, in the presence of nature, on the other.” She was not the only curator who responded so passionately. In 1983, Bates was chosen for the Corcoran biennial, and by 1987 he had earned his own spot in the Whitney’s.

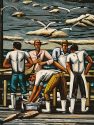

After Grassy Lake, Bates turned his attention to the Texas Gulf Coast of his childhood, a far more open and light-filled environment in which he immortalizes what he has called the “blue-collar heroism” of the men who worked on the water. “I’ve always felt like David is a successor to Marsden Hartley,” says Jock Reynolds, director of the Yale gallery, referring to the pioneering American modernist. “There’s the same painterly affinity for the subject matter and empathy for the people he paints. You can tell he’s comfortable hanging out in the bait shop.”

Also, as a serious fisherman himself, Bates knows well the challenges of the job. In Night Fishing, for example, he set out to capture the drama and uncertainty of what happens “anytime you get out in nature at night.” It’s no accident, he says, that the lanterns in the piece seem skull-like.

At the Modern, Bates’s Galveston paintings were hung with his most serious works to date, a series of “Katrina portraits,” painted first from television images during the first awful days of the New Orleans flood, and then from sketches of the battered city and its citizens made during a visit just a few months later. The portraits, said one critic, “upped the empathetic ante.” Bates has long had a gallery in New Orleans and has fished nearby on countless occasions—what he saw unfolding on his screen was personal. But as with his far earlier portrait of Ed Walker, he says he never expected them to be met with the success, both critical and commercial, that they immediately found. “The paintings were something he had to do,” says Marla Price. “There was no decision about it.”

Along with the Galveston works, they represent for Bates the two sides of the Gulf: as a “productive life force” and an agent of destruction. “The Gulf paintings make the Katrina paintings less sad,” he says, “and the Katrina paintings make the Gulf things look more heroic.” Together, then, the paintings create an epic narrative, which is something Bates finds lacking in the work of many of his contemporaries. “You can slather paint; it’s interesting, but…I needed to communicate. Here, it’s more about stories. I’m interested in the stories of Eudora Welty and Faulkner.” While he says that some of the Katrina paintings have the components of a short story, the narrative of most of his work is usually a bit more “backdoor.”

What all the pieces possess is an unmistakable muscularity. He jokes that even his still lifes are anything but still. And in a monograph of Bates’s work, Justin Spring writes that his flowers “are among the most hefty and energized in the history of American painting. They are also among the most playful; in many instances they seem to possess all the charm of a well-loved pet.” Bates and Jan both got a huge kick out of that—and it’s even more true of the sculpted works. Walking through the Nasher show, we all stopped in front of Daffodils, a painted bronze that is among my favorites. “That’s a butch daffodil right there,” Bates said, laughing, but it is true. It’s not unusual to discover bits of rebar winding through magnolia blossoms; in Sunflowers the “seeds” at the center of each blossom are formed by pushing plaster through the extruded metal of a toaster oven rack.

Bates began focusing on sculpture in earnest about sixteen years ago, but his paintings had been gaining an almost 3-D quality for some time. At the Modern, when we paused in front of Stringer of Sheepshead, Bates pointed out the viscosity of paint he had piled onto the fish. “They look like they’re gonna pop off the line.” Likewise, in Evening Storm, he says, “paint is so much like clay and I had a bunch of it left on the table. So I scraped it up and slapped it on [a cloud at the top of the canvas]. It made it look more like a cloud to me. Of course, those things just as easily don’t work, and then you just scrape it off.”

His early sculptures were made at a foundry in Walla Walla, Washington, but in the last several years, he has worked closer to home, in Houston, with increasingly lighter materials. At the Nasher, we examined a painted bronze, Dog with Wagging Tail, and as he pointed out the cast materials—the pieces of plywood and cardboard, the old place mat and wicker basket—they were all easy to identify. “They told me anything you can burn with fire, you can cast, so I went nuts with that.”

The dog is painted so that the bronze looks almost as though it is wood, a technique Bates employs a lot, but some of the pieces are more somber and imposing, as in the unpainted bronze magnolias he created just after what he calls “the time release funerals.” His parents, to whom he was extremely close, died just a few months apart, in 1997 and 1998. “That and Katrina,” he says, “are the two biggest events as far as changing the work, making it more serious.” The magnolia has long been a totem of sorts for Bates—he paints or sculpts one every few years to keep tabs on his evolution. Jan’s Magnolia, which went home to the Dallas house the couple recently bought and renovated, was painted in 1986 and was the “logo” of the Modern show. Black Magnolia I, one of the sculptures made after his parents’ deaths, stood at the entrance of the Nasher show. “When it’s just bronze,” Bates says, “it has a different kind of beauty to it than a painting or a painted sculpture.”

His latest pieces are both more playful and abstract. Four recent skulls, for example, are made of cast and painted cardboard. “A guy sent me a bunch of supplies, and the supplies got messed up but the boxes still looked good, so I used them,” Bates explains before launching into an imaginary conversation with a Manhattan gallery owner: “‘Dude, dude, I made these skulls out of some boxes.’ The guy would be like, ‘Did you have a stroke?’ And that’s another thing about not being so caught up in the art world. It gives you the freedom to do what you want to do.”

What he wants to do—whether it’s painting fishing guides or Katrina survivors or making sculpture out of cardboard—almost always turns out for the best. “The skulls and [mixed media] owls are just astonishing,” Marla Price says. “They are so elemental—there is nothing extraneous whatsoever. He had the vision to see them that way, and that’s a very powerful thing.”

At the Nasher, Bates was allowed to pick pieces from the museum’s permanent collection to display in a room alongside his own work, so he went for the big boys among his influences: Matisse, Picasso, de Kooning. “The curator said, ‘You know, you’re gonna have some of the world’s greatest art next to yours and that’s not always good,” Bates said, grinning. “I’m like, ‘Mmm, okay.’ It’s a good thing it’s not too embarrassing.” Price goes further. “When I first went to the Picasso Museum in Paris, I was knocked out by how many little sculptures there were everywhere, like he took a phone call and made a sculpture,” she says. “I think David has that kind of manual energy and talent.” When I venture to Bates that not only was the juxtaposition of the work with that of the earlier masters not embarrassing, it uplifted his own pieces, he agreed, and gestured toward three painted plaster, steel, and wood heads. “Those heads right there have never looked better than they do right now.”

Bates is a very funny but low-key and self-effacing man, so if he is finally displaying a tiny touch of bravado, it is well deserved. At the museums, he is treated like a rock star—one man who drove up from Houston told him it was one of the best shows he’d ever seen. The husband of an art teacher said his wife was too shy to introduce herself but that she was his biggest fan. Always he was solicitous and kind (“You teach high school art? Man, that’s the black belt!”). If he also has achieved rock start status in the wider world as well, he certainly doesn’t behave like it. His and Jan’s new house, complete with pool and sunny art studio, is the most spacious they’ve ever lived in, but not by any means grand. And, since Jan had a hand in almost every detail, it is, like her, seriously warm and welcoming. Their favorite vacation spot remains the Gulf Coast, but lately they head farther east to either Seaside or WaterColor in Florida. And, as always, Bates will fish every chance he gets.

As we walked through the Modern, where two of the four Bates canvases owned by Yale were on view, Bates remarked, referring to the gallery’s director, Reynolds, “Yeah, that guy seems to like my work.” When I expressed surprise that they’d never met—most artists are mad to cultivate collectors and curators, after all—Jan said, “No, no, that’s not us. It’s the work.” The good news is that the work turns out to be all it has taken to put him at the top of a game he never played. During the same exchange about Yale, Bates joked that he could never have gotten into the place as a student. Later, when I repeat the line to Reynolds, he says, “Well, he’s here now. Tell him he’s been admitted four times.” And though Reynolds would be happy to meet the artist he so admires, it’s not what matters to him either. “Frankly, the work is just powerful. It can take care of itself.”