By Lesley Dill via The Brooklyn Rail

When I was 14 years old growing up in Maine I experienced a startling awareness of understanding. I was in my bedroom getting ready to go to school and looking out the window at the late fall oak leaves against the early morning sky. Suddenly everything became black and I became all eye. All I could see was a darkness shot through with threads of light. Suddenly, I saw horrors and war and murder and heard the words “pestilence” and “ ravaging.” I could feel an almost crystalline pattern and was submerged in an understanding of the world. I felt that “everything was all right.” I was suspended in what I now know was bliss and comprehension.

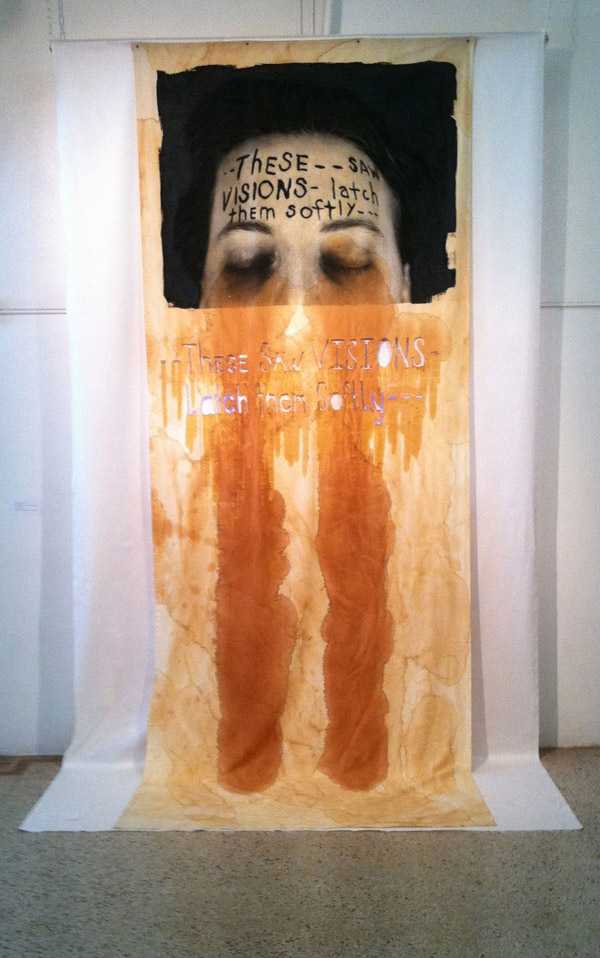

Lesley Dill, “Poem Eyes #3,” photo silkscreen shellac, thread on tea stained muslin. Courtesy of artist and George Adams Gallery.

I was late for school, so I just went downstairs and had Cheerios. I had absolutely no memory of this experience, no memory of it at all, and it wasn’t until I was a junior at Trinity College and taking a class called “Ecstasy” and reading William James that I would. The professor asked us lightly if anyone in class had ever had a moment when time stood still, or had had a vision. I immediately knew what he was talking about. The details of my vision came back to me fully formed. I said nothing, never spoke of it, this gift of seeing the world. I thought I would be put on medication or others would think that I was telling a tale. I married two husbands and never spoke of it. I had no context for it.

It wasn’t until I was 50 that the way opened for speaking about this. I am an artist living in N.Y.C. and I was invited to be an Artist-in-the Community in Winston-Salem for a period spanning almost two years. I didn’t know what to do for a big project, and then the thought came to me. Maybe down South, maybe there I would find other people who had had spontaneous revelatory experiences. So I called the project “Tongues on Fire: Visions and Ecstasy,” and there I had to share my vision over and over. I found 700 people in the community who had had recurring dreams, moments when time stood still, and a few had comprehensive large experiences. I remember one woman told me she was driving her car, and she looked sideways out the window and “saw all of life.” Most experiences were very short, but also very memorable, with people touching base with their memory at least once a week.

I am still confused about my vision. Where did it come from? What does it mean? What to do I do with it? I mainly know that it has opened up my inner mind in a large way. And I find that my artwork now often deals with ideas of contrasting good and evil: knowing that the world holds them both. My husband is a foreign video journalist who has brought home stories from Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Liberia, Nigeria, Rwanda, and South Sudan. These stories make sense because they were already revealed to me in my early vision. I practice Buddhist meditation to ground myself because I still have experiences of unasked for ecstasy. I am drawn to the poets Emily Dickinson (“Take all away from me but leave me Ecstasy”), and John Donne (this soft ecstasy), as well as Dante’s Inferno (“hell evil war murder witch king suicide fear body parts flood catastrophe cataclysm fire,” and Tom Sleigh (“How perfect and luxurious to be the slut of nobody and nothing and nowhere”). It is writing and poetry that has ultimately in recent years, given me an acceptance and understanding of wild, dark grace. And it is the writers and poets whose words spark new visions in me that enable me to make art. Their words speak to the metaphor of the “Known Unknowable.”