by Mora J. Beauchamp Byrd for John Scott Retrospective at the Masur Museum of Art in Monroe, Louisiana

Mora J. Beauchamp Byrd

Dr. Mora J. Beauchamp-Byrd is a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies at Duke University. An art historian, curator, and arts administrator, she has most recently served as Interim Executive Director at the New Orleans African American Museum of Art, Culture and History (NOAAM). Here, she adapts her exhibition catalogue essay (Yesterday’s Doorway: John Scott’s Iconographic Portraits of New Orleans) for an exhibition entitled “John Scott Retrospective,” organized in 2008 by the Masur Museum of Art in Monroe, Louisiana, in collaboration with the Arthur Roger Gallery.

Spirit House: John Scott’s Iconographic Portraits of New Orleans

In 2002, John T. Scott and Martin Payton completed a collaborative project entitled Spirit House (Fig.1 ), a massive sculpture placed at DeSaix Circle in the Gentilly area of New Orleans. A monumental aluminum structure reaching a height of nineteen feet, Spirit House evokes both a soaring cathedral and the vernacular, everyday quality of the shotgun house. Indeed, the work’s central form is the relatively narrow shotgun, yet it is suspended above a base of eight flying buttresses (supports built against a wall for reinforcement), deftly echoing those found on Gothic and Gothic-inspired cathedrals throughout Europe. This towering, expansive configuration allows visitors to walk beneath, and therefore within, the space.

In 2002, John T. Scott and Martin Payton completed a collaborative project entitled Spirit House (Fig.1 ), a massive sculpture placed at DeSaix Circle in the Gentilly area of New Orleans. A monumental aluminum structure reaching a height of nineteen feet, Spirit House evokes both a soaring cathedral and the vernacular, everyday quality of the shotgun house. Indeed, the work’s central form is the relatively narrow shotgun, yet it is suspended above a base of eight flying buttresses (supports built against a wall for reinforcement), deftly echoing those found on Gothic and Gothic-inspired cathedrals throughout Europe. This towering, expansive configuration allows visitors to walk beneath, and therefore within, the space.

In 2002, John T. Scott and Martin Payton completed a collaborative project entitled Spirit House (Fig.1 ), a massive sculpture placed at DeSaix Circle in the Gentilly area of New Orleans. A monumental aluminum structure reaching a height of nineteen feet, Spirit House evokes both a soaring cathedral and the vernacular, everyday quality of the shotgun house. Indeed, the work’s central form is the relatively narrow shotgun, yet it is suspended above a base of eight flying buttresses (supports built against a wall for reinforcement), deftly echoing those found on Gothic and Gothic-inspired cathedrals throughout Europe. This towering, expansive configuration allows visitors to walk beneath, and therefore within, the space.

Most striking are the series of silhouetted, cut-out figures that cast, at various points during the day, a shadowy march of figures across the grassy earth below. These relatively abstracted yet clearly articulated forms include a vibrant group of jazz musicians, ancient Egyptian and West African motifs, church choirs, poetic inscriptions, masquerading figures, animal forms, and an industrious series of laborers at work (Fig. 2). In an April 2002 article in the New Orleans-based Times-Picayune, Scott is quoted as stating that the work’s silhouetted forms relate the narrative of the “unnamed, unknown, African American bricklayers, iron workers, fruit vendors, domestics and teachers who built this city” (McCash 2002), referring to the work as an “urban tabernacle” (McCash) that references Egyptian and Greek temples as well as the vernacular Afro-Caribbean shotgun design. Scott further noted that “we’re hoping that it becomes…symbolically important to the community” (McCash).

It is particularly fitting that Scott would pointedly reference the emblematic connotations of Spirit House. In fact, his entire oeuvre has mined the symbolic qualities of the African diddley bow (an American stringed instrument of African origin), the crucifix and Catholic iconography in particular, the Egyptian pyramid, West African sculptural traditions, and a host of other sources. This essay examines Spirit House, placing it in context with other Scott works, to highlight an overarching theme of New Orleans-related symbolism that is present in nearly every phase of the artist’s career.

John Scott was born in New Orleans in 1940 and earned a B.A. from Xavier University of Louisiana in 1962. He received an M.F.A. from Michigan State University in 1965, and was a faculty member at Xavier for more than forty years. Scott is best known for vibrantly colored and multi-layered prints as well as graceful kinetic sculptures fashioned from industrial metal rods, whisper-thin wires and fueled by a complex system of weights and counter-weights. His work ranges from sophisticated, eloquent kinetic sculptures influenced by the diddley bow to delicate line drawings of unparalleled draftsmanship. Stylistic diversity and a heightened engagement with global art historical precedents is perhaps the defining characteristic of his work. In 1992, he received a prestigious John D. MacArthur Fellowship, commonly called the MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship. After evacuating New Orleans just before Hurricane Katrina in 2005, he remained in Houston and died there in September 2007 after a lengthy struggle with pulmonary fibrosis.

Scott’s oeuvre, while stylistically and thematically diverse, may be nonetheless grouped into several content-based areas: urban scenes, with a particular focus on New Orleans; music and musicians of African descent (including a pronounced focus on jazz and Louis Armstrong as iconic figure; re-workings of art historical styles and motifs (including tributes to various artists); spiritual evocations with a focus on Catholicism; celebratory images of women; and social commentary.

Funeral for Louis

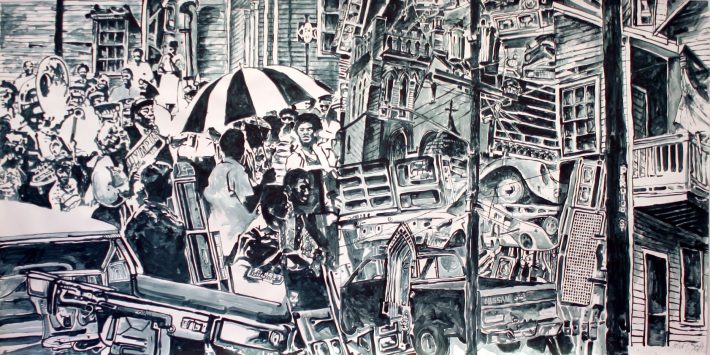

An acrylic on paper of 2003 entitled Funeral for Louis (Fig. 3) exemplifies Scott’s focus on New Orleans-based music and musicians. Here, a jazz funeral or second line procession is in progress, a scene framed by a compressed assemblage of houses, automobiles, and street signs. Punctuating the processional scene is one of the ubiquitous open umbrellas that remain a virtual necessity at these events. For many New Orleanians, the image of a twirling umbrella conjures an entire history of “second-line” parade traditions, described by anthropologist Helen A. Regis as “massive moving street festivals…organized and funded by working-class African Americans to celebrate the anniversaries of their distinctive social clubs and benevolent societies” (Regis 1999). Regis also notes the additional function of a “second line” procession: as jazz funeral “to mark the passing of community members” (Regis 1999).

In Funeral for Louis, a street pole labeled “Perdido Street” is also visible, a clear reference to Louis Armstrong’s youth in New Orleans as well as to the significant role of the area in the history of jazz. Around 1914, Armstrong began working as a musician in the various clubs and other night-time establishments that permeated the Perdido Street/South Rampart area of New Orleans during this period. For many, the area is considered the site of the birthplace of jazz. Buddy Bolden frequently played there between 1900 and 1906, in particular at a converted church at 1319 Perdido Street that later became known as Funky Butt Hall (see Hardie 2002). In addition, the area also relates to Armstrong through his second wife Lil Hardin (1902–71), a talented pianist and composer who produced numerous classic tunes during her tenure as part of King Oliver’s Band, including “Perdido Street Blues” in 1926.

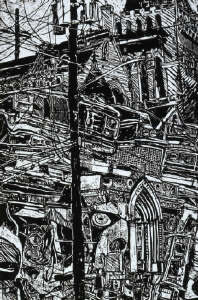

A woodcut series called Blues Poem for the Urban Landscape seems to have been extrapolated, bit by bit, from Funeral for Louis. The series includes Storm’s Coming (Fig. 4), an image punctuated by windswept debris that captures the precarious nature of life in New Orleans, a frequent hurricane and tropical storm route. Somehow this work, and the Blues Poem series in its entirety, appear to have foreshadowed the climactic events of 2005. The image entitled Cathedral (Fig. 5) from the series references the city’s lengthy history of Catholicism and hints at a significant narrative about African American Catholicism in the area1. Yesterday’s Doorway (Fig. 6) depicts a dilapidated doorway that functions as an apt symbol for the weather-beaten yet resilient city of New Orleans.

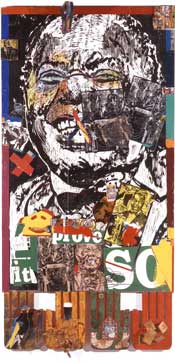

So Prove It (Fig. 7) is a mixed-media collage and assemblage that may be described as a Robert Rauschenberg-like “combine” forming a pictorial dialogue with New Orleans-linked individuals. A central image of Louis Armstrong is flanked by a bird at bottom left; repeated reproductions of Scott’s prints of renowned sculptor and printmaker Elizabeth Catlett; a second-line musician; West African sculptural forms and several three-dimensional elements such as a paintbrush, a pointed reference to Scott’s focus on highlighting the practice of art-making. In the upper middle register of So Prove It, a second line musician appears to both mourn Armstrong’s passing and celebrate his life as well.

So Prove It also references Scott’s lengthy friendship with the distinguished African American artist Elizabeth Catlett, who has lived in Mexico for more than fifty years, but has long maintained a connection with New Orleans, beginning with her time as Professor of Art at Dillard University in the early 1940s (for a discussion of Catlett’s early years, see Lewis 1984, Beauchamp-Byrd 1996, and Herzog 2000). Scott’s symbolic pairing of Armstrong, a New Orleans native who achieved worldwide prominence, and Catlett, who produced an iconic sculptural image of Armstrong in Armstrong Park, commissioned by City of New Orleans in the 1970s, pays tribute to several of Scott’s own highly personal sources of artistic and musical inspiration.

Treme Cornice

New Orleans architecture is also ever-present in Scott’s work, as exemplified by work entitled Circle Dance: Treme Cornice (Fig. 8). The image is part of a series of kinetic sculptures that Richard Powell has described as “a multisculptural assembly of bronzes on the intersecting themes of the blues, jazz, family, friends, and of course, New Orleans. Opting for the visual unity that comes from treated bronze’s green, viridescent patina, Scott constituted a kind of stylized stageset/dreamworld in the series’ initial installation at the Arthur Roger Gallery in New Orleans during the spring of 2001. The other unifying elements—the repetitive use of seesaw appendages attached to cables that were strung…across large, circular forms—gave the sculptures…the sensibility of fantastic maquettes—model-size constructions that nodded and swayed like their kinetic forebears (sculptures by Alexander Calder and George Rickey, the antebellum dancers in Congo Square, the traditional jazz funeral’s “second liners” (see Powell 2005). Here, Powell situates the Circle Dance series in performance-based cultural practices that are quintessentially New Orleanian.

Treme Cornice in particular references two important symbolic elements that are critical to New Orleans culture and history. Treme is a neighborhood located on the northern side of the French Quarter that was settled in the early 19th century by free people of color. It has often been called the first African American community in the nation. Cornices are decorative elements located at the uppermost section of a building, projecting forward from the main walls; exterior cornices were initially used to direct rainwater away from a building’s main walls. Cornices are also seen indoors, as molding applied to the uppermost part of a room wall. Houses throughout New Orleans are distinguished by their fine cornices, some of which are decorated with appliquéd rows of floral and animal elements.

Cornices, medallions and other forms of decorative work on ceilings and windows represent the detail-oriented artistry of plasterers. Twentieth-century New Orleans plasterers like Louis Alexander, Earl Barthe, Amdee Castenell, Sr., Herbert Gettridge, Sr., Thomas Lachin and William “Smitty” Smith have been highly sought-after for their complex and polished decorative designs. Their work, alongside those of brick masons like Teddy Pierre, carpenters like Sal and Sterling Doucette, Ivy Gaudet, Henry “Hank” Gueringer, and Russell Plessy; along with lathers like Allison “Tootie” Montana and metalsmith Lionel Ferbos, are also called forth by works like Treme Cornice and Spirit House (see Spitzer 2002).

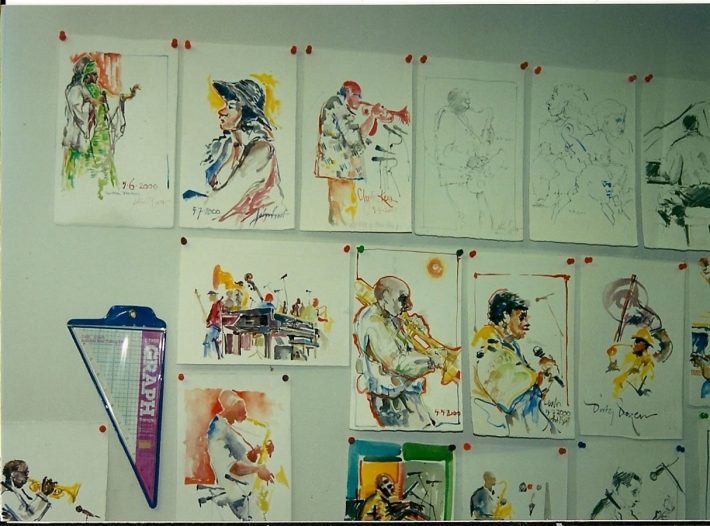

In addition to his engagement with the legacy of artistry in the construction of the city, Scott has also explored New Orleans’ festival traditions as theme, best exemplified by a prolific series of small-scale watercolor and Japanese sumi ink drawings on paper that chronicle performers and observers during Jazz Fest in 2000 (Fig. 9). These delicate and jewel-like studies reflect Scott’s stunning virtuosity with line, space and color, and reveal his heightened enthusiasm for this quintessentially New Orleanian festival.

Spirit House

Scott’s skillful use of New Orleans as creative and symbolic source may be best evidenced in the aforementioned Spirit House, which elevates the shotgun, a vernacular, residential structure, to the canonical status of the Gothic cathedral. Commissioned by the Percent for Art Program of the City of New Orleans, Spirit House is a complex series of silhouetted forms in a style that is highly reminiscent of Haitian metal cut-out sculpture. Fashioned from aluminum sheet and painted a teal-like hue, the work’s weather-beaten and oxidized appearance signifies solidity and permanence, as does the work’s placement atop eight columnar forms. The silhouetted figures of Spirit House represent an encyclopedic catalogue of iconographic references: a Chi Wara antelope head of the Bamana of Mali, a Gabon reliquary mask, a Yoruba horseman, a symbol of the sankofa bird with its head craned backwards, a symbol for the Akan of Ghana that represents a reverence for history, and the shotgun house with its Afro-Caribbean roots and historical relevance in the city of New Orleans. Spirit House greatly benefits from the combined pedagogical drives that fueled John Scott’s life and work, and the highly advanced facility with welded metal that marks Martin Payton’s distinguished sculptural works. A New Orleans native, Payton has been an Associate Professor of Art History at Southern University since 1990, and his influences include traditional West African sculpture and dance, African-derived belief systems, Egyptian art and Abstract Expressionism.

In Scott and Payton’s celebration of the laborers who literally built New Orleans, they also reference a host of other imagery that directly pays tribute to the city’s rich melding of creolized influences shaping its distinctive culture. Reinforcing the work’s symbolic content, the artists attached several explanatory plaques at eye level on the interior sides of the eight columnar bases. Each panel details the various thematic components of the work in sections such as “The Roof”, “Symbols”, and “Spirit House Shadow”. The “Middle Passage” panel includes a graphic image of a crowded slave ship hold and text that discusses the “dense pack” design of these vessels, ending by noting that Africans “brought various elements of their culture with them.”

“Occupations” documents the role of African American labor in the building of the New World, while “Shotgun House” charts the route of the shotgun house structure from West Africa to “the Caribbean Islands to New Orleans”. The text for the section on the “Flying Buttress” notes that Spirit House “symbolizes the European influence upon the African American religious culture at their time of arrival in a new country,” an invocation of the prominent role of Catholicism in the area. The work, while primarily focusing on African American contributions to the Americas and punctuated by a focus on African-derived cultural influences, is just as much a paean to the city of New Orleans as it is to the broader, historical issues of race, religion and migration that it calls forth.

In particular, by positioning the shotgun form as the primary symbolic core of Spirit House, Scott and Payton definitively link this work to the city’s African descendants, despite the ongoing scholarly controversies relating to the role of West African construction in the development of American architecture. Anthropologist Jay Edwards has written of how this contentious dialogue has largely focused on “the contributions of black Creoles and African Americans in the establishment of the urban cultural landscape of New Orleans” (Edwards 1999). Edwards notes that anthropologist John Vlach’s groundbreaking 1973 study argued that the shotgun house “is an African architectural legacy that developed in Saint Domingue [the French colony later renamed Haiti]. First adopted by marooned slaves and then transmitted to the cities of Saint Domingue, it was later carried to New Orleans by Haitian refugees, particularly by the slaves and the affranchis” (Edwards). The term affranchis is derived from affranchisement, a French term meaning emancipation. Affranchis may be defined as emancipated slaves in the context of Haiti and other French Caribbean colonies. These communities, many of whom were either of mixed race and/or born free, played an integral role in the building trades (see Hankins and Maklansky 2002).

Edwards cites the fact that both enslaved Africans and affranchis “integrated themselves into the building trades in the 1820s and 1830s,” and “reproduced the familiar shotgun in their North American homeland” (Hankins and Maklansky). Vlach’s theory has long been overwhelmingly embraced. Yet, as Edwards points out, there have been opposing views: some architectural historians believe that the shotgun is a local innovation evolving from the city itself, with little or no African-derived input. Scott and Payton’s Spirit House, however, in casting the shotgun as emblematic foundation, have squarely documented the inextricable linkage between New Orleans, Africanized cultural manifestations, and the builders of African descent who largely produced the city’s residential and institutional structures.

In a 2004 interview in Sculpture magazine, Scott discussed several elements of the symbolism that is critical to the work, noting that

I collaborated with a former student and dear friend of mine, Martin Payton, on Spirit House. It was a collaboration based on the neighborhood where it was going to be built. It was a neighborhood where great craftsmen once lived…We asked ourselves, what is an African American? We decided that an African American is an African who was brought to America under duress. What’s the symbol for an African American? Being in New Orleans, we thought the hippest symbol we could use was a shotgun house, which came to New Orleans by way of the Caribbean from the Old Country. Then we thought, what makes an African American? There’s this African-European fusion. So we needed a European counterpart. When we were brought to New Orleans it was controlled by the Spanish and French, which translates to Catholic. So we decided to put a shotgun house on flying buttresses (Stunda 2004).

Scott’s remarks emphasize the significance of the actual site, in Gentilly, the “neighborhood where great craftsmen once lived,” an historically relevant space in the city’s landscape. His remarks also highlight the significance of New Orleans as cultural crossroads, a creolized’ city in every sense of the term.

Both Scott and Payton have noted that the work should be viewed as solidly grounded in its history as well as its present and future, a fact further exemplified by the actual processes that shaped the work’s execution. The work’s creation was marked by community-based engagement. Inscriptions on several placards note that the artists collaborated with students from two local elementary schools, Medard H. Nelson Elementary and St. Leo the Great Catholic School. In the end, thirty-seven students produced highly accomplished design drawings for the North and South walls of the shotgun, the “Occupations” and “Symbols” sections.

Spirit House, as well as other works produced throughout Scott’s career, references the “busy,” rhythmic quality of New Orleans life: the melding of shotguns, Creole cottages and soaring churches, alongside the city’s cacophony of sounds, from the early-morning hawking of produce to the frenzied flow of second-line processions. Both the Blues Poem series as well as Spirit House exemplify Scott’s skillful mining of New Orleans-based symbolism: the shotgun house, an open umbrella above a lively procession, a cathedral passageway, or a weathered iron balcony railing, seen from the streets below. All of these symbols, in Scott’s hands, brilliantly conjure those enigmatic, historically-resonant qualities that distinguish New Orleans from any other city. As Scott stated in a 1992 interview, “New Orleans is the only city where—if you listen—the sidewalks will speak to you” (Rive 1992).

Notes

1Significant texts that have documented African Americans and Catholicism in Louisiana include Davis 1990 and Deggs 2001. In addition, I served as curator of a 2008 exhibition project, accompanied by a catalogue, that examined the 166-year history of the Sisters of the Holy Family (SSF), the second oldest Catholic religious order for women of color in the United States. Entitled “A Celebration of Faith: Henriette Delille and the Sisters of the Holy Family,” and on view at the New Orleans African American Museum of Art, Culture and History from April-August 2008, the project detailed the 1842 establishment of the SSF in New Orleans by three free women of color, and their establishment of numerous schools, churches, nursing homes and other missions.

Bibliography

Beauchamp-Byrd, Mora J. “An Aesthetic of Survival: The Visionary Art of Elizabeth Catlett,” in Struggle and Serenity: The Visionary Art of Elizabeth Catlett. New York: The Caribbean Cultural Center, 1996.

Davis, Cyprian. The History of Black Catholics in America. New York: Crossroad Publishing, 1990.

Deggs, Sister Mary Bernard. No Cross, No Crown: Black Nuns in Nineteenth Century New Orleans. Edited by Virginia Meacham Gould and Charles E. Nolan. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Jay D. Edwards, “What Louisiana’s Architecture Owes to Hispaniola (and what it does not),” Louisiana Cultural Vistas, Summer 1999, 45.

Hankins, Jonn Ethan and Steven Maklansky, eds. Raised to the Trade: Creole Building Arts of New Orleans, exh. cat. New Orleans Museum of Art, 2002.

Hardie, Daniel. Exploring Early Jazz: The Origins and Evolution of the New Orleans Style. iUniverse, 2002.

Herzog, Melanie Anne. Elizabeth Catlett: An American Artist in Mexico. Seattle and London: The University of Washington Press, 2000.

Lewis, Samella. The Art of Elizabeth Catlett. Claremont, CA: Hancraft Studios, 1984.

McCash, Doug. “Sculpture Whispers Tales of Orleanians, Present and Past,” The Times-Picayune, Friday, April 5, 2002.

Powell, Richard J. “Circle Dance,” in Circle Dance: The Art of John T. Scott. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2005.

Helen A. “Second Lines, Minstrelsy, and the Contested Landscapes of New Orleans Afro-Creole Festivals.” Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Nov., 1999), 472.

Rive, David. “A Sculptor of Culture.” The Times-Picayune, January 17, 1992.

Spitzer, Nick. “The Aesthetics of Work and Play in Creole New Orleans,” in Jonn Ethan Hankins and Steven Maklansky, eds. Raised to the Trade: Creole Building Arts of New Orleans, exh. cat. New Orleans Museum of Art, 2002.

Stunda, Hilary. “Playing It Straight, Upside-Down, and Backwards: A Conversation with John Scott.” Sculpture, October 2004, Vol. 23, No. 8.