by Grace Ebert for Colossal

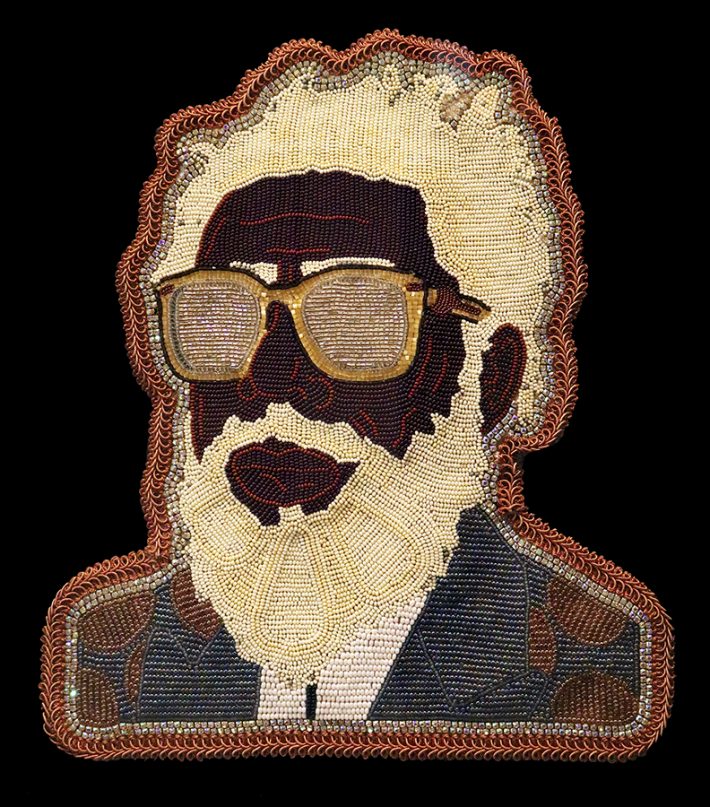

Through intricately woven displays of minuscule glass beads and rhinestones, Big Chief Demond Melancon continues a legacy. He belongs to the tribe of the Young Seminole Hunters in New Orleans, where he was born and raised, and is a leader in the tradition of creating Mardi Gras suits. The “wearable sculptures” are elaborate and celebratory, and Melancon’s works are known for their immense nature and for exhibiting his deft technical skill. Extremely labor-intensive, the garments tend to envelop their wearer in multiple layers and contain more than one million glass beads precisely stitched into evocative narratives of American history.

For nearly three decades, Melancon has also developed a unique visual language that is both entrenched in the 250-year tradition and working to expand the scope of the practice. “The elders, the Indians, and the Black maskers that masked before me, they never saw this as a contemporary art form in the way that I do,” he tells Colossal. “To me, the elders are watching me, and I think what they taught me is different from what I’ve evolved it into.”

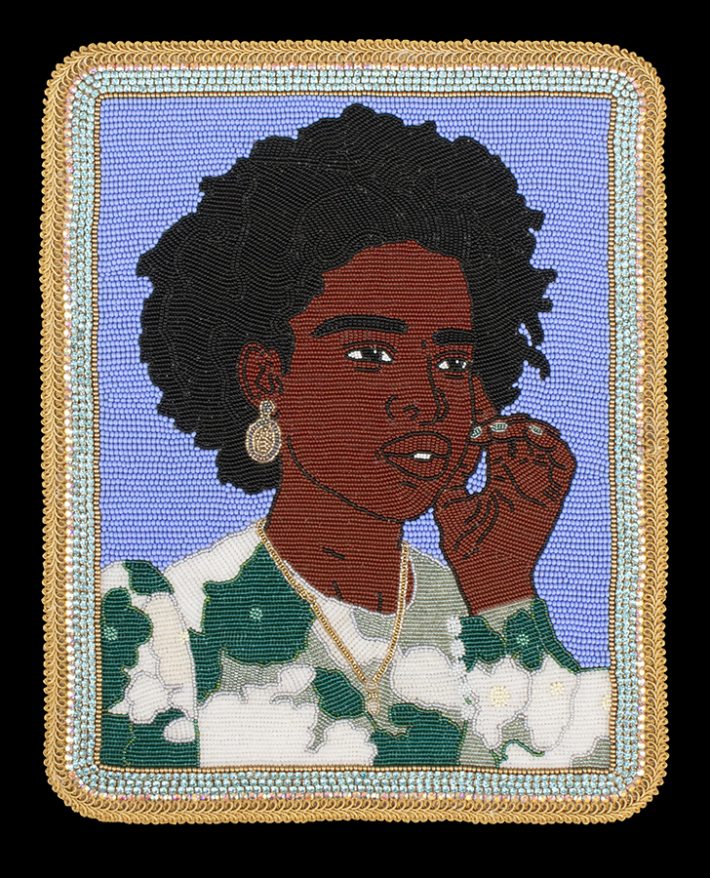

Often encircled by feathers, many of Melancon’s suits revolve around portraits of reggae icons, people who were enslaved and subsequently led revolts, and Mardi Gras Indian Big Chiefs who came before him. He’s also started to separate these figurative elements from their more comprehensive counterparts in recent years and has produced an extensive series of standalone portraits. The ongoing collection includes people who have been influential in his life and who have broad cultural relevance, including artists like Basquiat and Frida Khalo, ancient Egyptian queen Nefertari, and Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black woman killed by police in 2020. “I like to teach with my work, and I want to make something that’s very meaningful,” he says. “It’s going to tell you something. It’s going to hit you in your heart.”

Sometimes years in the making, Melancon’s portraits exemplify his commitment to transforming the small, tactile materials into compositions evocative of painting. He references artists like Kerry James Marshall(previously) and Kehinde Wiley (previously) as inspiration and is equally drawn to those working today as he is to the art historical canon. His style emerged “through studying Botticelli and Caravaggio. I like the light in the old-school paintings, in the Florentine art, in the art from the 1700s.”

Beginning with a black-and-white sketch, Melancon always completes his subjects’ eyes first to “try to bring people back to the living stage with the portraits… so they can live, and they can look at me while I’m beading the rest of the piece.” For the artist, this spirited energy and sense of vitality are directly derived from his bold color palettes that compose a floral blouse or radiant, crown-like headdress.

Although Melancon didn’t mask for this year’s Mardi Gras—instead, he helped garner grants for those participating in the festival through his work on the New Orleans Tourism and Cultural Fund board—he’s currently in progress on a suit titled “Amistad,” in reference to the historic 1839 revolt on the slave ship by the same name. He also plans to continue his portrait series and will see “Say Her Name,” the striking rendering of Taylor acquired by the International African American Museum, on view at the institution when it opens this fall in South Carolina. It’s one of many works that Melancon sees as part of his duty to pass down stories to future generations and teach them about those who’ve profoundly shaped the world today. “That’s another piece that I think in this time very important,” he shares. “People should remember her situation, and that’s why I bead.”

To explore Melancon’s full portfolio, visit his site and Instagram.