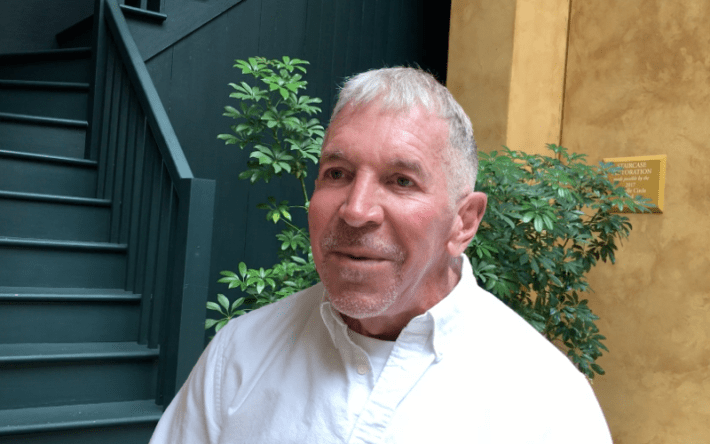

A New Orleans native, Dureau (1930–2014) studied art at Louisiana State University and architecture at Tulane University and served in the US Army. When Roger first met him in the 1970s, Dureau was known more as a painter and for his drawings.

“I was in college,” Roger said. “I worked at a gallery on Royal Street. I was a framer. And the French Quarter was a very different place then. There were a lot of eccentric people, and George was one of those very noticeable people that were in the Quarter.”

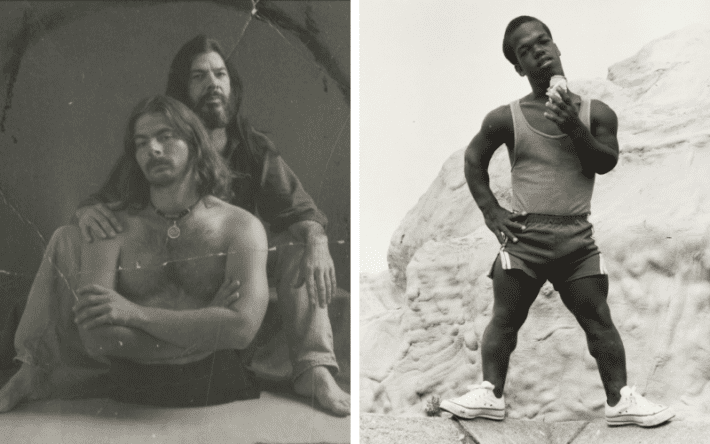

Dureau’s photography began as reference material for his other artwork, which frequently portrayed characters of mythology and religion (such as in his “The Parade Paused” mural, displayed inside Gallier Hall, where countless Carnival parades drawing on mythological themes have paused over the decades).

“If you work with anyone who does figurative work, they are always looking for models or they’re looking for some way to have a visual reference,” Roger said. “The photographs in the beginning were clearly for him to have a reference for his paintings. Then, later, I think he really grew and was able to recognize something he could do.”

“There was nothing casual about it”

Frequently cited as an influence on Robert Mapplethorpe (Roger once staged a comparative gallery show of both photographer’s work), Dureau’s photographs were never serendipitous, said Roger, who like many of Dureau’s friends and acquaintances posed for him.

“There was nothing casual about it,” Roger said. “Everything was very deliberate. Your head was forced in a very uncomfortable position. Your arms and shoulders and legs — there was nothing that wasn’t pushed into a place where he wanted it. You would feel that this is going to look terrible. When you saw the results of it, it looked perfectly normal. There was never anything accidental. That was part of who he was.”

Dureau was “a pure photographer,” Lawrence said, whose talent lay in his meticulous craftsmanship. “He was responsible for the posing, the lighting, the concept of the pictures, and releasing the shutter.

“The studio offers a lot of control for the photographer, maybe less so for the subject. When you’re in the studio, you’re kind of in there because the photographer wants you there.”

Extraordinary works

The Prospect.5 exhibition features studio photographs as well as images taken outdoors in various locations around the city, including the French Quarter, where Dureau maintained a noticeable persona until near the end of his life.

Suffering from dementia, he became the focus of a small group of concerned neighbors. The “Friends of George,” organized by email, helped see him through the early stages of decline before his relocation to a care facility. Roger, enlisting Dureau’s half-brother Donald Dureau, arranged for The Historic New Orleans Collection to acquire a trove of Dureau’s photos, artwork, and life ephemera.

“This was a Louisiana artist who had established himself in multiple fields of achievement,” Lawrence said. “That was an important thing for us.”

Said Roger: “Files, little prints – anything that looked of any importance, we boxed it and gave it to The Historic New Orleans Collection. We felt that it was a tremendous victory for George’s legacy.

“For George, I think it was a problem to recognize, in my mind, that the photographs were the most important body of work that he had done. Locally, I think that’s quite the opposite. I think locally, people really embrace the paintings and drawings more. But there’s no question in my mind that [his] photography will go on well beyond any of this.

“You know, I cared about him a lot. I think he had this quality that you would only see in New Orleans in that particular time. It’s a terrible loss, but I think he left us with extraordinary works that are going to be remembered for a very, very long time.”