Gordon Parks “Department Store”, Mobile, Alabama, 1956

Two years after the ruling, Life magazine editors sent Parks—the first African American photographer to join the magazine’s staff—to the town of Shady Grove, Alabama. His assignment was to photograph a community still in stasis, where “separate but equal” still reigned. Parks arrived in Alabama as Montgomery residents refused to give up their bus seats, organized by a rising leader named Martin Luther King Jr.; and as the Ku Klux Klan organized violent attacks to uphold the structures of racial violence and division.

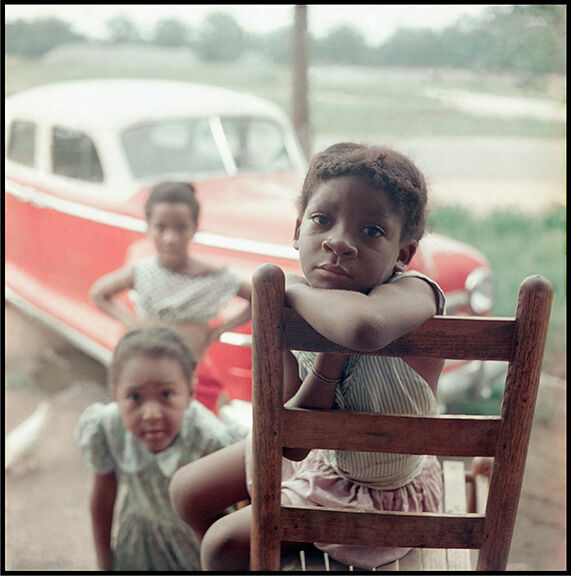

Gordon Parks “Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama”, 1956

Gordon Parks “Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama”, 1956

A lost record, recovered

Gordon Parks “Untitled, Harlem, New York”, 1963

After 26 images ran in Life, the full set of Parks’s photographs was lost. In 2011, five years after the photographer’s death, staff at the Gordon Parks Foundation discovered more than 200 color transparencies of Shady Grove in a wrapped and taped box, marked “Segregation Series.” The first presentations of the work took place at the Arthur Roger Gallery in New Orleans in the summer of 2014, and then at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta later that year, coinciding with Steidl’s book. Parks was a self-taught photographer who, like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, had documented rural America as it recovered from the devastation of the Great Depression for the Farm Security Administration. At Life, which he joined in 1948, Parks covered a range of topics, including politics, fashion, and portraits of famous figures. His series on Shady Grove wasn’t like anything he’d photographed before.

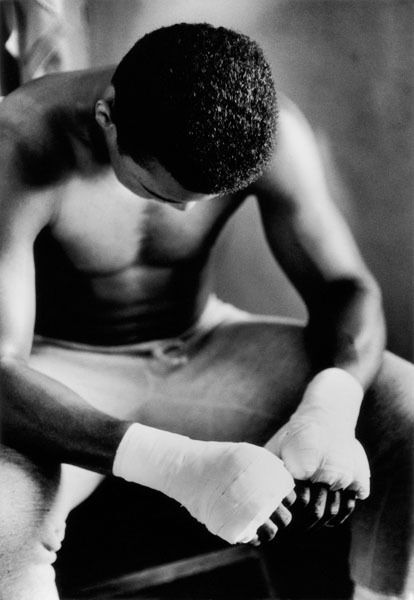

Gordon Parks, “Muhammad Ali in Training, Miami, Florida”, 1966

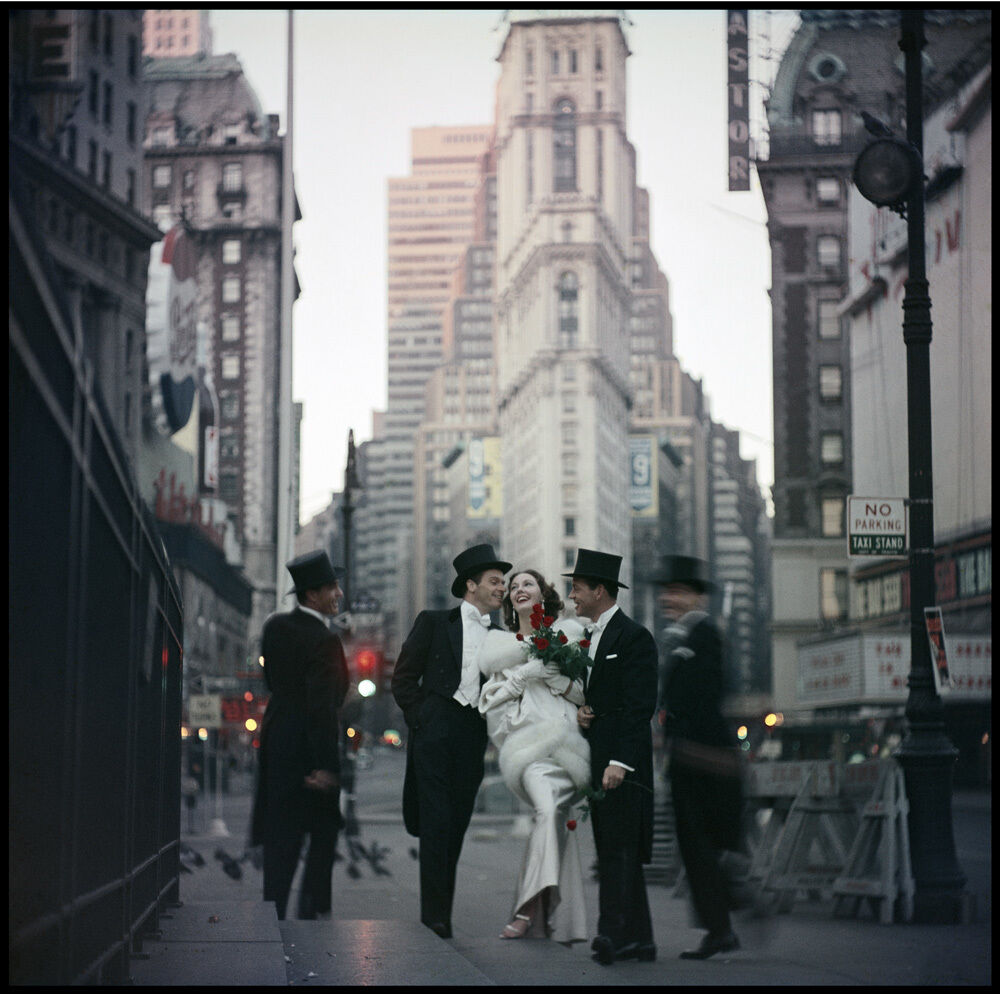

Gordon Parks, “Cocoon Cape, New York, New York (30.003)”, 1956

Parks faced danger, too, as a black man documenting Shady Grove’s inequality. “With a small camera tucked in my pocket, I was there, for so long…[to document] Alabama, the motherland of racism,” Parks wrote. Life found a local fixer named Sam Yette to guide him, and both men were harassed regularly. In his writings, Parks described his immense fear that Klansman were just a few miles away, bombing black churches.

Gordan Parks, “Untitled, Alabama (37.042)”, 1956

Images of affirmation

Gordon Parks, “At Segregated Drinking Fountain”, 1956

Despite the fallout, what Parks revealed in Shady Grove had a lasting effect. It was more than the story of a still-segregated community. Black and white residents were not living siloed among themselves. In his images, a white mailman reads letters to the Thorntons’ elderly patriarch and matriarch, and a white boy plays with two black boys behind a barbed fence. (This image has endured in pop culture, and was referenced by rapper Kendrick Lamar in the music video for his song “ELEMENT.”—a visual homage to Parks.) The intimacy of these moments is heightened by the knowledge that these interactions were still fraught with danger.