BY JOHN D’ADDARIO | Special to The Advocate MAR 27, 2018 – 2:00 PM

The nearly two dozen artists in the Ogden Museum’s “The Whole Drum Will Sound: Women in Southern Abstraction” are — as advertised — women from the South who make abstract art.

But their similarities end there.

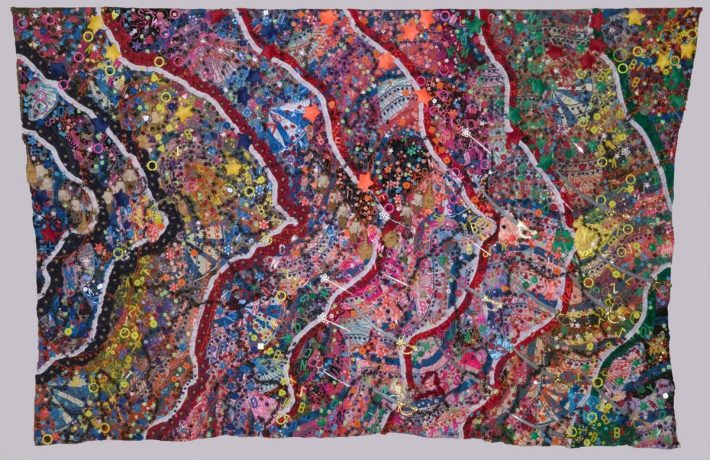

In one gallery, Shawne Major’s riotously colorful assemblage of plastic toys and fiber contrasts with a nearby Jacqueline Humphries painting dominated by stark red slashes, like the aftermath of a violent act. A pair of jewel-like drawings by self-taught artist Minnie Evans couldn’t be more different from Valerie Jaudon’s grid of curvilinear forms, a marvel of technical precision.

According to curator Bradley Sumrall, the show’s eclecticism is by design.

“The show isn’t trying to define some kind of universal ‘feminine aesthetic,’” Sumrall said. “It’s simply an opportunity to look at some of the best examples of work produced by female artists.”

Opening near the end of Women’s History Month, it’s tempting to view the show in light of current social issues like the #MeToo movement. But while the title (derived from a quote by French writer Amin Maalouf) may suggest otherwise, “The Whole Drum Will Sound” is largely free of polemics — though some works addressing environmental concerns creep in around the edges.

And Sumrall’s installation, which separates work created in the 1950s and 1960s from more contemporary examples, more strongly invites a reconsideration of how these artists fit into a broader art historical context.

So you start to wonder why an artist like Dusti Bongé, whose work is comparable to that of any number of her better known male contemporaries, has been relegated to a minor regional footnote in the history of 20th-century modernism — and how that kind of chauvinism relates to other gender disparities in society.

The show is revealing in other ways too.

New Orleans’ own Ida Kohlmeyer, who Sumrall posits as the bridge between the older generation of artists in the show and a newer one, is represented by early paintings that show the influence of Mark Rothko, with whom she studied. They will be a surprise to those who are only familiar with the 3-D works she created from the 1980s until her death.

Also surprising is the art of Kohlmeyer’s sister Millie Wohl, who studied with Hans Hoffman. (Apparently the sisters, who had a contentious relationship, were rivals as competitive golfers as well as artists.)

And three works by Vincencia Blount, who Sumrall calls “the Atlanta equivalent to Ida Kohlmeyer,” make a convincing case for those of us in another part of the South to become better acquainted with her work. One consists of pieces of canvas patched together with monofilament like some sort of abstract Frankenstein’s monster.

Two nearby works by contemporary artists show a similarly engaging use of materials. Bonnie Maygarden’s almost photographic abstract texture is painted with enamel on leather, while Ashley Teamer’s painting shows a young artist approaching abstract space using a variety of methods: Paint is poured, dripped, brushed and spread with a palette knife.

Inside the main fifth-floor gallery, highlights include Betsy Stewart’s microcosmic landscape wherein dense layers of calligraphic marks suggest looking through a microscope at diatoms and dividing cells. Nearby, a giant grid of Shawn Hall’s biomorphic abstractions reads like oversized slides from a similar experiment.

The reflective aluminum surface of Margaret Evangeline’s “Sfumatoshinoclysm,” riddled with faux bullet holes, substantiates Sumrall’s claim that Evangeline is “one of the only artists who can get away with glitter.”

Sherry Owens weaves branches of crape myrtle, their surfaces whittled, stained and waxed to accentuate natural textures and patterns, into a form that suggests a heart, or a womb. Clyde Connell’s wall pieces, with figures trapped by or emerging from a tangle of branches, are among the closest the art in the show gets to representation.

And most impressively, Dorothy Hood’s “Florence in the Morning,” with its spare forms suggesting a bird in almost limitless space, reads like a visual koan. It’s not surprising to learn from Sumrall that Nobel Prize-winning poet Pablo Neruda was inspired to write about Hood’s work.

“The Whole Drum Will Sound” is full of such discoveries. It’s a sound worth listening to closely.

****************

“The Whole Drum Will Sound: Women in Southern Abstraction”

WHEN: Through July 22

WHERE: Ogden Museum of Southern Art, 925 Camp St., New Orleans

INFO: (504) 539-9650 or ogdenmuseum.org