by Chris Waddington, via nola.com

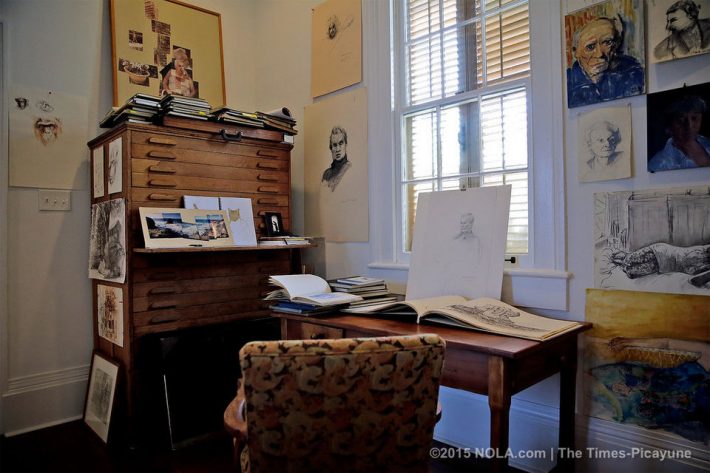

Simon Gunning, and his new studio in Faubourg Marigny in New Orleans, photographed on Thursday August 20, 2015. After decades working in a cramped attic studio at his adjacent home, Gunning worked with wife Shelly to convert a neighboring shotgun into a comfortable studio to make his large scale landscape paintings. (Photo by David Grunfeld, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune)

Simon Gunning struggled through eight months of eight-hour days to paint the centerpiece of his latest New Orleans exhibit: A mural-scaled aerial landscape composed of millions of tiny brushstrokes. That same attention to detail comes through in the Faubourg Marigny studio where he works, a shotgun built circa 1815, which he restored with wife Shelly Gunning and master builder Robert Fullen.

“I worked in the attic of my house for 30 years – cold in winter, hot in summer – and I was ready for a change,” Gunning said. “I didn’t need an industrial loft after that. I wanted something comfortable that matched New Orleans and its surroundings – the environments I have been painting since the 1980s.”

Gunning found the perfect studio next to his home, across a landscaped brick alley lined with potted sweet olives, citrus trees and a trickling fountain made from a sugar-boiling kettle. For his morning commute, Gunning slips on sandals, paint-spattered clothes and takes ten steps to the studio with a cup of coffee in hand.

“I’m in love with the light in this space, and I’m able to control it precisely because of the shutters,” Gunning said. “The shutters were custom made from sinker cypress, and it was worth the expense. In the course of a day, I’m always tweaking the louvers and leaning them open. Plus, they give me privacy without closing me off from the street. I can be painting and still see pedestrians passing. That’s a big plus when working alone all day.”

Both the light and the proportions of the new studio left a mark on Gunning’s work. About half of his forthcoming exhibit, which opens Oct. 3 at Arthur Roger Gallery, 432 Julia St., was painted in the restored shotgun. (Art critic Doug MacCash included Gunning’s exhibit among the “5 Best Bets” of the annual Art for Art’s Sake openings on Saturday).

“I moved into the studio in July 2014 and immediately began a series of aerial views of New Orleans – a new subject for me. It helped to be in a space with 13-foot ceilings, and long sightlines. I can see from end-to-end of this building, so 900-square-feet seems much bigger than it is. That was a practical advantage when painting a 12-foot by 5-foot canvas that I needed to get out the door. But the studio also helped me think differently. The wrong kind of workspace can be very disruptive when you’re looking inside yourself, trying to understand the world with a paint brush in hand.”

To create that perfect workspace, Gunning relied on his wife, Shelly, who has cultivated an eye for beautiful things on a bohemian budget – and sometimes no budget at all.

The studio’s antique brass window locks and pulls were salvaged two decades ago, discards from a CBD hotel that was undergoing renovation.

“I stored those for years and never could bring myself to get rid of them,” Shelly said. “When we started working on the studio, and rebuilt all the original windows, I knew it was time. We cleaned off a lot of paint and tarnish and found that we had beautiful brass pieces that we couldn’t have afforded otherwise.”

In fixing the windows, Shelly and her contractor were especially careful about preserving the antique glass. She collects old sheet glass and had a small supply of it to make repairs.

“It seems like a tiny detail – the ripples and bubbles in a pane of antique glass, but it’s one of the things that makes this building feel anchored in history and in our neighborhood. It’s the kind of thing you just can’t imitate,” she said.

The Gunnings like old things, but they’re not uncomfortable with today’s styles. They added a modern kitchen and polished contemporary bath to the studio building, which also serves as an entertainment space when clients come calling.

As with many renovated New Orleans homes, the bones of Gunning’s studio building were preserved under layers of later additions. A hanging 1960s ceiling hid historic bead board in the light-filled entrance hall. Slabs of red-pine bargeboard, about six-inches-wide, had been hidden by carpet and linoleum. The 9-foot cypress pocket doors, now restored with their original brass locks, were discovered nailed to the walls of the garden shed.

“I love being surrounded by all this old wood,” Simon Gunning said. “It tints the light and enriches the texture of my rooms. I often find myself looking at the knots and grain of the floorboards: It’s like staring at clouds. I see all kinds of things hidden in those patterns.”

Shelly Gunning, a passionate gardener and gourmet cook, shares her husband’s taste for old wood and timeworn objects.

“I grew up in Chalmette and wasn’t visiting auctions houses and art galleries as a child. But I always collected things: shells from the beach, beautiful stones. I like primitive things, and I think that comes through in the way I decorate,” she said.

She pointed to a studio bench, a weathered slab of cypress, about four inches thick, that she saved from the dump a few years ago.

“I was driving down Poland Avenue, saw this piece on the curb, and hit the brakes. A work crew had pulled it from under a house while cleaning an overgrown yard. I gave them $15 dollars and asked them to throw it in my trunk. The workers thought I was crazy – and so did Simon until I took the wire brush to it and showed him how beautiful that old wood really was.”

When she does shop for furniture, she often is drawn to the hidden gems, buried under dust in retail storerooms. Among her finds, an antique wooden drafting table that sits beside a dark-stained bench her husband saved from John McCrady’s long-gone French Quarter art school. Simon’s workbench, heaped with brushes and squashed paint tubes, is exactly that – a scarred carpenter’s bench that dates back a century. Shelly topped its rough surface with beveled glass.

“Some people don’t like rough pieces that show how they were used. But that’s exactly what I look for,” Shelley Gunning said. “Both Simon and I are people who have always worked. We respect old tools and old furniture. Those things tell stories about the past and the people who owned them. I think a house should be like that, too: Full of stories. I suppose that’s what I also like about Simon’s paintings.”