By Rupert Goldsworthy via artinamericamagazine.com

Andy Warhol never painted the great female Broadway belters Ethel Merman, Sophie Tucker or Barbra Streisand. While making paintings of almost every female superstar of his era, Warhol curiously avoided making any work based on la Streisand or Merman. The New York painter Deborah Kass became well known in the 1990s for a series called the “Warhol Project” where she expertly reproduced paintings of Barbra in a style very reminiscent of Warhol’s mid-1960s screen-prints and in a manner that seemed to correct the omission.

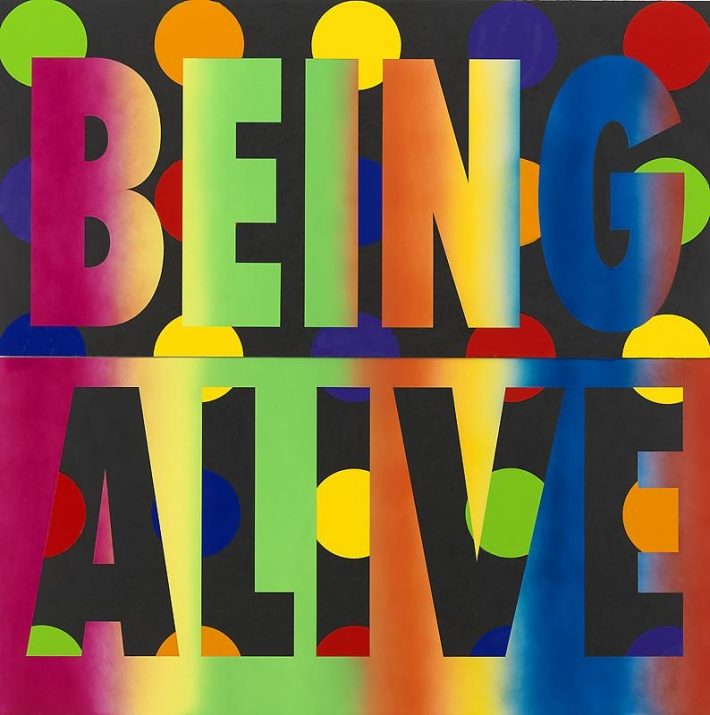

BEING ALIVE, 2010. COURTESY PAUL KASMIN GALLERY, NEW YORK.

In her latest series, “MORE feel good paintings for feel bad times,” currently on view at Paul Kasmin Gallery in New York (until October 30), Deborah Kass extends her Broadway connection and revives showtunes and post war painting to explore the intersection of politics, popular culture, and art history.

Moving from utilizing photographic sources to mining text, Kass’ paintings replay Broadway song lyrics, from Stephen Sondheim, to Garland, to Seventies folk singer Laura Nyro, while simultaneously sampling the visual tropes of Abstraction and Pop, from Warhol, Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella and Ed Ruscha. Kass’ new work sharply updates and juxtaposes mid-century cultural production, highlighting its contemporary resonance for our current political era. In her paintings Kass replays and demystifies the post-war canon of the Greenberg era, hijacking earlier Modernist tropes making a deliberate deconstruction/ reconstruction/appropriation of the whole masculinist painterly Abstraction shtick, replacing the alienated word-play of Sixties Pop with the emotional effusiveness of Broadway lyrics. The question is why is classic Broadway relevant to painting now? Kass unpacks this and other questions during the interview.

RUPERT GOLDSWORTHY: One of the many things I find interesting and unusual about your work is the rigor of the actual physical process of its making, and the time you take to duplicate tricky art canonical techniques. You earlier mimicked Warhol’s silkscreen style flawlessly, and now you master the techniques of 50s-6s abstraction associated with Stella and Newman. Have you had a long fascination with hard-edge abstraction? In “Frank’s Dilemma” the quality of the cutting and edging is very sharp and hard, the image is a rainbow swirl of colors and letters, but on closer inspection, it is rigorously cut and taped to perfection. People always discuss your subject matter and its relation to identity and gender, but can you talk about the handling of materials? What draws you to recreate the high-precision of Modernism and Pop? Is that part of the fascination for you, of mastering a particular technique associated with another artist very precisely?

KASS: The making of these paintings is very not too fussy, and very direct. I learn what I need to in order to reference the artists I am referencing. If it’s not fairly right on, it will be distracting. There’s a lot of taping and many many layers of paint. I am not interested in fetishizing the object, but they do have to stand as objects, and I do love “pretty.” I am entirely indulging the decorator in me, the mid-century decorator.

GOLDSWORTHY: You are well-known for your work “The Warhol Project” where you reproduced Warhol’s 1960s screenprint style but using Streisand as the subject. When The Warhol Project ended, what happened next?

KASS: The plan was to take a year off from making art, something I had never done before, and finish up some commissions. It was spring 2001. I travelled a little and spent a summer in Provincetown living on the bay, watching the sunsets at Herring Cove as many nights as possible The next April I got back to work as scheduled the day after I turned 50 and spent 12 months taking the advice I would have given anyone in my position, finished with a defining body of work of many years, ready to move on, but not sure in which direction to go. I sat in at my drawing table and drew.

The new work was intended to have all the content of the Warhol series but in a different form. Like the Warhol project, this work would refer to art history, popular culture, and the construction of the self. One way of formulating a self is through the process of identification. What is it in the world that holds our attention? What music do you like, what art, which stars, what shows? What grabs you in popular culture and cultural production? How does that define you?

GOLDSWORTHY: Can you talk a little about the piece “Day after Day” a 6ft by 21ft piece, a seven-panel rainbow color-chart painting which stretches the length of one wall of the gallery, repeating the phrase “Day after day after day after day”, drawn from the Stephen Sondheim lyric. This work has a slightly different vibe to the other paintings in the show. Whereas “C’mon Get Happy” and “Forget Your Troubles” seem to celebrate the optimistic, against-all-odds drive of Garland, Broadway, and the US post-war era, “Day after Day” suggests some duality here?

KASS: Well I actually think most of the other paintings have that same double edge, but perhaps not as sharp an edge as “Day after Day”. That’s the genius of Sondheim. That particular lyric, at that particular scale seemed so very pertinent. The oil leak was just happening, along with so many other horrible things that just go on and on. At that scale, the painting is temporal, it exists in space, you can’t take it in in one look, you have to walk through it. What does one do now except put one foot in front of the other and go on day after day? Whatever one’s reasons for doing so. That’s what we all do. Go on. Day after day.

GOLDSWORTHY: Why go back to Broadway as a reference point?

KASS: I couldn’t think of anything that was more profoundly American, optimistic, or personal with which I identified, (and as embarrassingly, I might add, also Streisand.). In the middle class world of tri-state New York, baby boomers were raised on this music. The albums, the music were ubiquitous in middle-class homes. The music was incredibly popular, recorded on “Original Broadway Cast” albums and reinterpreted by giants like Sinatra, Fitzgerald, Vaughn and Holiday.

Recently I came across this quote from Patricia Highsmith: “For where does genius show itself more brilliantly in America than in the creation of musical comedy?” And despite pop art, what could possibly be more of an affront to the silly snobbery of the art world-(most of whom were born to people who were or aspired to the middle class)—after appropriation dismantled ideas of “originality,” than the notion of middle class entertainment? Class is the last frontier. Suddenly I wanted to be an out and proud member of the middle class, the very thing my baby boom generation was raised in and supposedly rejected.

Now that era looks like the golden age of America. Think of the art and music that came out of that time. By combining great post-war painting with the great American songbook, I was hoping to remind us of some of our greatest cultural exports and a time when there was a great American middle class to support their production. The children of my generation seem to agree. What else could explain the popularity of the TV show “Glee” and its endlessly downloaded soundtrack of numbers from Broadway’s greatest musicals?