PHOTOS OF LOUISIANA PRISONERS RENEWED DEBORAH LUSTER’S PEACE OF MIND

By Doug McCash, The Times-Picayune

Art critic

Photographer Deborah Luster doesn’t try to connect the dots. In conversation, she lays out the autobiographical steppingstones that led to the creation of “One Big Self: Prisoners of Louisiana,” her 2002 masterpiece now on display at the Newcomb Art Gallery. But she leaves us to fill in the psychological blanks.

“One Big Self” is a collection of more than 1,000 photographs of inmates in Louisiana prisons, including the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. Luster visited the prisons between 1998 and 2002, seeking inmate volunteers who allowed her to take their portraits.

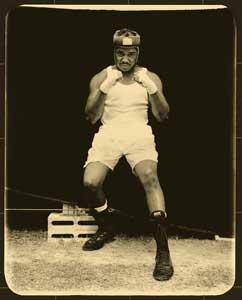

She used a black backdrop to remove any modern prison features from the background. To further remove her photos from the contemporary world, she printed them in black and white on small sheets of metal with an amber colored glaze, reproducing the look of the tintype photos popular during the Civil War. She gave each inmate paper copies of his or her portraits — they were not allowed to have sharp metal objects.

Gallery visitors are welcome to sort through the photos in the glare of a bureaucratic gooseneck lamp atop a sinister steel cabinet that clanks like a prison cell door when the drawers are shut.

The photos are sometimes forbidding, but more often they are strange and sad. Bulging prison-yard muscles and macho tattoos can’t disguise a sense of defeat. Unsmiling faces radiate regret. Occasional smiles radiate it even more. Luster said the prisoners cherished their portraits. One said he was shocked to discover he had grown so old. Some chose to be photographed holding a picture of a family member, bonding with their loved ones in Luster’s camera.

The strangest photos capture prisoners in Halloween and Mardi Gras costumes, or the cowboy gear worn during the annual Angola prison rodeo. One photo shows an inmate costumed as Christ for a prison Easter pageant. Modern details, such as an electric guitar, do nothing to disturb the impression that these pictures could have been taken in the horse and buggy era.

There’s a political component to “One Big Self,” of course. By creating present-day inmate portraits that appear to be antiques, Luster slyly suggests that while the rest of the world has undergone social and technological sea changes, incarceration is essentially the same as it has been for more than a century.

To visually emphasize the scope of incarceration, she has included a small book filled

LSP15, 1999, Print on aluminium, 5x4 inches.

with the seemingly endless serial numbers of those jailed in Louisiana as of the first day of the 21st century. She’s forgotten the exact count. But beyond artistic activism, there is an unseen personal motivation at work.

Luster, 56, was born in Oregon and raised in Arkansas. In an interview last week, she said her mother was murdered in 1988 by a hired killer, who was later convicted of the crime. She declines to elaborate on the details, but she said the incident so frightened her that she became terribly withdrawn and isolated. She feels photography helped her “get out in the world.” In 1998, she was one of several photographers hired by the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities to document life in northern Louisiana. She found that prisons were one of the major industries in the poor parishes. She was allowed to enter the East Carroll Parish Prison Farm, where she first photographed inmates. The results so compelling that she dedicated the next four years to laboriously creating “One Big Self.”

Luster spent only a short time with each inmate and she doesn’t claim to have gained any deep psychological insights. “I don’t want to presume to know who they are,” she said. “I’m simply showing you them.” She said she was not frightened and had a “great time” taking the portraits. “If someone lets me photograph them, lays themselves bare, I love that,” she said. “I’m grateful.”

To have overcome her mother’s murder with the help of photography, which then led to her sympathetic documentation of prison inmates, would have been a strange enough turn of events. But in conversation, Luster revealed another odd detail of her background. Her stepfather was an American prisoner of war in Poland during World War II, and helped dig tunnels that led to the mass prison breakout known as the “Great Escape,” she said. The concept of incarceration had always been part of his identity — and to an extent, Luster’s.

Luster doesn’t draw the threads of her life together to create a nice tight bow. She says that all these years later she’s not certain why she was so compelled to fill her lens with prisoners. And she allows that she’s not sure how crime victims will view her photos of “people who may have killed their loved ones.” All she’s sure of is that, in the end, “One Big Self” was personally cathartic.

“It’s very mysterious,” she said. “I had a very heavy heart for a very long time, but when I started photographing (prisoners) and handing photos back to them, I found it quite transformative. All that lifted. I don’t understand it.” In 2002, I chose the debut of “One Big Self” as the No. 1 art exhibit of the year, but never felt it got the exposure it deserved. Thanks to the Newcomb Art Gallery, Luster’s postmodern tour de force can be seen through Feb. 24. If “One Big Self” weren’t enough reason to visit the out-of-the-way exhibit space, the gallery is also showing a large suite of works by Diane Arbus and an exhibit of antique photo techniques.