Renowned artist stayed close to N.O. roots

Kinetic works lauded nationally

By Doug MacCash, NEW ORLEANS TIMES PICAYUNE

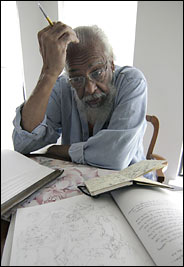

Artist and educator John T. Scott, one of New Orleans’ most nationally renowned and respected visual artists, died Saturday morning at Methodist Hospital in Houston. He was 67.

- Renowned artist stayed close to N.O. roots

Mr. Scott, who had suffered from pulmonary fibrosis for years, apparently died of complications from the disease and surgeries he underwent to overcome it.

Mr. Scott, a Xavier University art professor since 1965, was best known for large-scale abstract sculptures that can be found in Woldenberg Park, De Saix Circle, City Park and at the New Orleans Museum of Art.

He also created small sculptures, drawings and prints, including the 1993 poster for the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.

In 1992, Mr. Scott received a $315,000 John D. MacArthur Fellowship, popularly known as a “MacArthur genius grant,” in recognition of his work.

In 2005, “Circle Dance,” a major retrospective of his art, filled much of the ground floor of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Mr. Scott’s lifelong love of art might have been sparked when his mother taught him to embroider as a child, he said in a 2005 interview.

“My mother was embroidering a pillow case for a wedding present, and she was doing these elaborate roses and leaves. “I said, ”Mama, why are you taking so much time with this?” And she said, ”Because someday this is going to hold someone”s dreams.”

One of six children, Mr. Scott was born on a farm in Gentilly that supplied meat and produce to Kolb’s, then a well-known Central Business District restaurant. His father was the Kolbs’ chauffeur. When he was 7, his family moved to the Lower 9th Ward.

In 1958, Mr. Scott graduated from Booker T. Washington High School and began his formal art studies. He received a bachelor of arts degree from Xavier University and a master of fine arts degree from Michigan State University in 1965.

Pioneering talent

Sculptor Lin Emery said Mr. Scott’s work was already “extraordinary” when he was voted in as one of the youngest members, and the only black artist, in the cooperatively run Orleans Gallery in the 1960s. The gallery was a gathering spot for the most important local modernists of the era, including George Dunbar, Ida Kohlmeyer and George Dureau.

“He showed such talent and promise that despite the fact that he was younger than us, we wanted him in the gallery,” Emery said. Artist Willie Birch said Mr. Scott broke ground for the generation of African-American artists who followed.

“John, he would always get embarrassed when I’d say it, but I saw him as Mr. New Orleans in terms of the art world,” Birch said.

“In the African-American community, he was the first to be embraced by the white world. He was an artist of prominence that could rival anyone in the city. He became the role model, the pinnacle that all of us strove to be like. The beauty of John was that he was very humble and very, very giving. He was important to all of us who came after.”

Mr. Scott’s early sculptures included expressive bronze castings of Christ, but religious themes soon gave way to more political topics. In 1983 he received a fellowship that allowed him to study in New York with internationally known sculptor George Rickey, who inspired him to add moving parts to his works.

For the next two decades, Mr. Scott not only made sculptures that moved, he made that movement a symbol for the African-American experience.

Expression through motion

One of the best examples of his symbol-laden sculptural style is his 1990 work “Ocean Song,” created for Woldenberg Park. The aluminum rods at the top of the 16-foot-high kinetic sculpture rise and fall gently in the river breeze, producing visual patterns reminiscent of the jazz music Mr. Scott held dear. The taut wire that holds the rods is a reminder of the African diddley bow, a weapon that could be converted into a musical instrument.

Mr. Scott said the silvery rings that hold the moving rods represented circle dances that were performed at Congo Square by slaves, and the glinting pyramid legs also hark back to Africa. All of the symbolism is particularly poignant because the sculpture stands near the spot where slaves might have first disembarked in New Orleans from their forced transatlantic journey.

“I think of ”Ocean Song” when I think of John’s best piece,” Birch said. “The music constantly reverberates through that piece. It has a rhythm about it that speaks to everything I felt. I’m reminded of the black national anthem, ”Lift Every Voice and Sing.” That piece has a special meaning to me.”

- John T. Scott. Ocean Song, 1990. Woldenburg Riverfront Park, New Orleans

Despite his dedication to African-American themes, Mr. Scott didn’t feel the label “African-American artist” quite applied to him.

He mentioned in 2005 that he was included in the 1995 book “Art Today,” by critic Edward Lucie-Smith. “In that book, all these people are broken down into categories,” he said. “For example, Martin Puryear, Faith Ringgold, Sam Gilliam, myself, a bunch of us are called African-American artists. The thing is, I have more in common with George Rickey and Alexander Calder,” white sculptors who, like Mr. Scott, incorporated moving parts into their work. “The fact that I work in kinetic media (logically) puts me in with the kinetic sculptors.”

Loyal to local community

Mislabeled or not, by the mid-1990s Mr. Scott had become a nationally known figure. Yet he remained dedicated to the local art community and his Xavier students.

“I guess the most important thing for me was that he was always giving, asking for nothing,” said fellow Xavier art professor Ron Bechet. “He just wanted you to pass on the information. . . . In teaching, his work and how he dealt with people, he was very straight up and honest. He just laid it on the line. Students who had difficulty, they would give up, but he wouldn”t. If there were a bunch of people doing A work, he was interested in the student doing C work.”

“Part of my responsibility is to speak for my community,” Mr. Scott said in 2005. “I want young black kids to realize that, ”Hey, if that guy’s from the Lower 9th Ward down by Desire and he can do that, then I can do that.”

Mr. Scott remained an innovator in a variety of artistic media to the end of his life. He modified and updated an ancient African bronze casting technique, teaching his students an alternative to more expensive, time-consuming methods. He created a series of enormous woodcut prints dedicated to Louis Armstrong, using a small chainsaw to “draw” the designs and an asphalt roller to print them.

Even after Hurricane Katrina forced him to evacuate to Houston without his tools, he continued working, created a series of watercolor flowers unlike anything his fans had seen before.

His eastern New Orleans studio was badly damaged by the storm and flood. In 2006, still in Houston, he underwent two double lung transplant surgeries made necessary by pulmonary fibrosis. While he was disabled, thieves twice broke into his storm-torn studio, stealing machinery and several sculptures — possibly to sell as scrap metal.

”The only home I know”

Though Mr. Scott had appeared to be making strides toward recovery, he eventually succumbed.

In a June 29 phone interview, he said he hoped to return to his hometown as soon as his health permitted.

“That’s the only home I know,” he said. “I want my bones to be buried there. I belong there. I need New Orleans more than New Orleans needs me.”

Survivors include his wife, Anna Rita Scott; a son, Ayo Scott; four daughters, Maria Scott-Osborne, Tyra Joseph, Lauren Kannady and Alanda Rhodes; and six granddaughters.

Funeral arrangements are incomplete.

. . . . . . .

Doug MacCash can be reached at dmaccash@timespicayune.com or (504) 826-3481.