Lifelines

By D. Eric Bookhardt, GAMBIT WEEKLY

As years go, 2005 was a big one for acclaimed African-American sculptor John Scott. In May of that year, a retrospective exhibition of the then 65-year-old artist”s work was held at the New Orleans Museum of Art. It was a big success by all the measures that matter. It came down a couple of months later, in July, and then we all know what happened on the 29th of August, 2005, a date that will locally live in infamy along with the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor and the 9-11 attack on the World Trade Towers.

Scott had evacuated to Houston just before the storm, and learning over the following days that his home and studio were under water must have taken a toll. His lungs already suffered from pulmonary fibrosis, and as news from his beloved hometown went from bad to worse, so did his condition. So much so that in February of 2006, his doctors attempted a lung transplant. When his body rejected that first set of lungs, he received another. When this show was scheduled, his gallery dealer, Arthur Roger, hoped he would be well enough to at least come to the opening but, alas, he remains in his Houston hospital room to this day. While his body appears to have accepted the second set of lungs, the healing process has been excruciatingly slow, and so far he still requires oxygen and a ventilator machine.

So the nationally prominent sculptor, who as the longtime head of the Xavier art department has been a mentor to many, remains as suspended in time as our more hard-hit neighborhoods. In his absence, his work must speak for itself, and if we as a city tend to take our creative talent for granted, this expo provides an opportunity to take another look at Scott’s oeuvre in terms of its deeper meaning. The works on view are a fairly representative sample, but unlike much recent contemporary — dare I say generic — art, they are rooted in time, place and history. Like jazz patriarch Ellis Marsalis, Scott has been an eloquent spokesman for, and interpreter of, the street culture of this city, streets that he says will speak to us if only we take the time to listen.

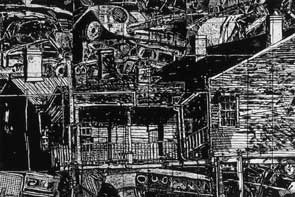

- John Scott’s large 2003 woodblock print, Blues Poem For The Urban Landscape, portrayed Katrina’s ravages two years before the storm.

They certainly spoke to him. This selection, almost a mini-retrospective in its own right, contains samples of his most emblematic efforts. Like the streets that inspired him, they are filled with color and motion. For instance, Circle Dance: Bunk Johnson”s Corner is a wall-mounted assemblage of circles and rods attached to an abstract form that might be either prosaic or Platonic, or both, depending on how it strikes you. Typical of his Circle Dance series, its suspended forms move with the breeze like a slow-motion ballet, but unlike much of his kinetic sculpture, this series features a weathered patina of the same pale oxide green that we see on old copper roofs. Related in form, but luminous with Scott’s characteristically electric colors, is Off the Edge: It Ain’t Olympus. Here the rods and circles connect to a structure suggestive of a house, another emblematic touch.

Rather than just containers for people, houses in Scott’s work have ritualistic quality as charged spaces where earthly and spiritual forces intersect — a quality amply demonstrated in large public commissions such as his Spirit House sculpture, strategically located at the intersection of DeSaix Street and St. Bernard Avenue.

If Scott sees the ancient, cracked streets of old New Orleans as places where magic spontaneously happens, he also knows that they are laden with baggage in the form of personal and social dysfunction. His Blues Poem for the Urban Landscape depicts them as a jumble of dilapidation with debris everywhere, cars on roofs and all the other anomalies we came to know so well after Katrina. But Scott created them in 2003, long before the storm, and what was surreal then became all too real all too soon thereafter. How did he know? The only plausible answer is that artists are sometimes prescient. For now, he remains confined to his hospital room, where the rest of us should beam our benedictions, prayers and best wishes for his timely and decisive recovery.