Amer Kobaslija captures Florida’s lush, strange atmosphere while examining the expressive potential of oil paint’s luminous, elastic, viscous goo.

by Edward M. Gómez for Hyperallergic

April 26, 2019

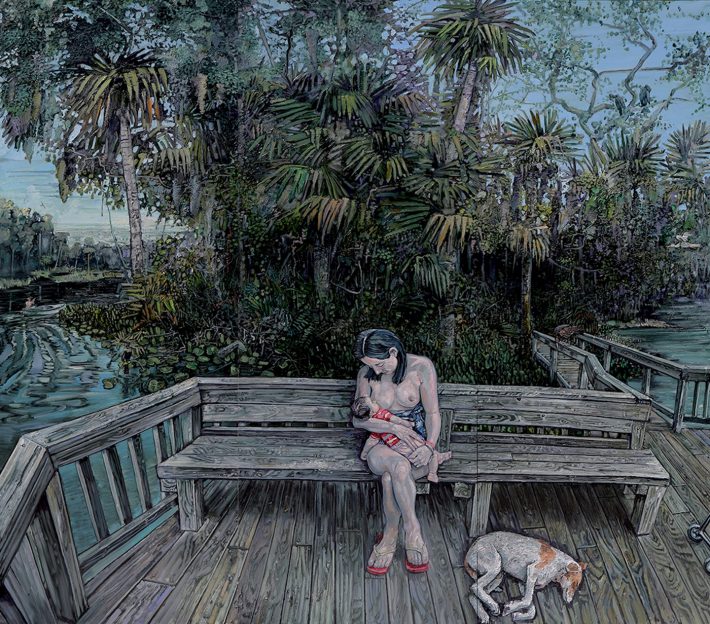

Amer Kobaslija, “Phoenix, Water’s Edge” (2018), oil on aluminum, 48 x 61 inches (© Amer Kobaslija, all photos courtesy George Adams Gallery, New York)

Real artists are always looking for something — either venturing out into the real world to bear witness to human behavior or to characterize places and events, or plumbing the depths of their imaginations in search of subjects and of innovative ways in which to address them.

The painter Amer Kobaslija, 44, has lived and worked in the United States since 1997, and last spring moved to Florida after having been based in New York for several years. For this Bosnian-born artist, the search for form and content often has meant trying to capture the atmospheres of his immediate surroundings — and, sometimes, those of places farther away — while also examining the expressive potential of oil paint’s luminous, elastic, viscous goo.

In recent years, Kobaslija has portrayed artists’ studios — his own and those of many others, including the rarely seen workspace in a village in western Switzerland of the modernist painter Balthus (1908–2001), whose full name was Balthasar Klossowski de Rola.

He further explored his interest in the notion of place in an ambitious series of pictures documenting the destruction and rebuilding of the Tōhoku region of northeastern Japan, which was hit hard by the earthquake and tsunami of March 2011. That project resulted in a series of about 150 paintings, which he executed over a period of several years.

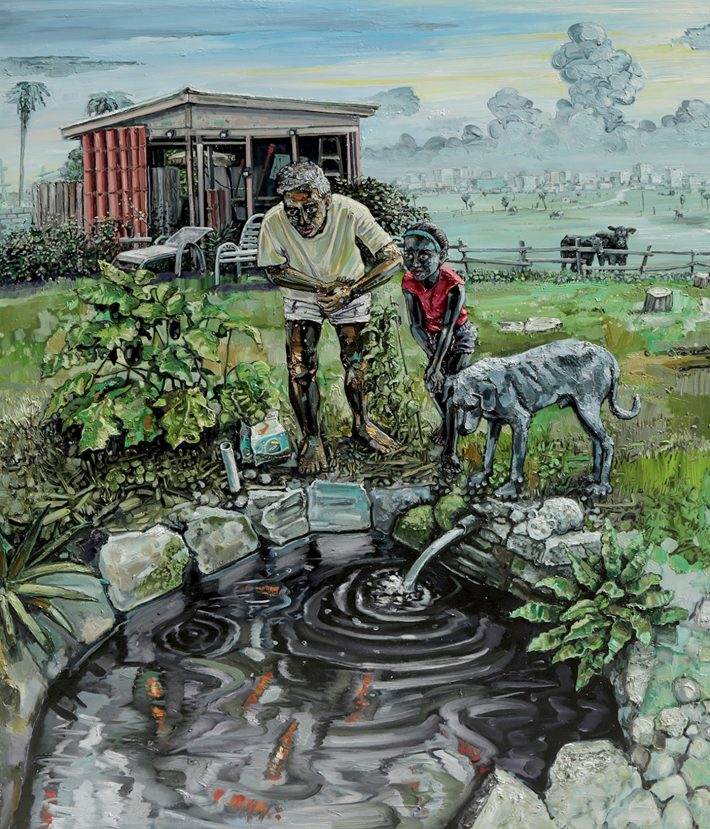

Amer Kobaslija, “Fish Feeders, Orange Park II” (2018), oil on aluminum, 70 x 60 inches (© Amer Kobaslija)

With a documentarian’s eye, a stylist’s deft handling of his materials, and a local’s appreciation for his subjects, Kobaslija again demonstrates that his art may be seen simultaneously as landscape painting, portraiture, and a form of contemporary history painting.

I had met and interviewed Kobaslija in the past at his former studio in New York. More recently, speaking by telephone from his home in Florida, where he now teaches painting in the School of Visual Arts and Design at the University of Central Florida, in Orlando, the artist told me about his newest works, noting, “They’re reflections on and of my surroundings; many of the characters in these paintings are friends or family members. These works implicitly reflect upon the society and the bizarre nature of the times in which we’re living. This is how I make sense of what’s happening out there — I internalize the world through painting.”

Even before leaving New York, Kobaslija had close ties to Florida. In the 1990s, he and his parents had settled there after fleeing their homeland, Bosnia, during the era of the Balkans’ sectarian wars. Prior to coming to the US, Kobaslija had studied in Germany at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where one of his main teachers was the American-Dutch video and multimedia artist Nan Hoover.

That humanistic approach is reflected in his new Florida paintings, just as it was in his series One Hundred Views of Kesennuma, which he began in 2011 following the natural disasters in Japan. Kobaslija’s wife is Japanese-born, and so he felt a sense of kinship with the stricken region, traveling numerous times to Tōhoku to make on-location sketches and, with the assistance of his wife or father-in-law as interpreters, gathering information about its affected communities.

In particular, he focused on the impact of the disasters on and around the coastal town of Kesennuma in the northeastern corner of Miyagi Prefecture, documenting in his paintings its eventual repair and rebirth, along with the gradual re-emergence of the natural environment. As the subject matter of Kobaslija’s Japan pictures changed over time, so, too, did his technical approach to making them; if thickly impastoed brushstrokes marked the earlier paintings in his series, with their images of billowing smoke rising from the smoldering remains of a once-active town, a relatively spare palette, applied with almost calligraphic strokes, typified some of his later depictions of nature’s determined regrowth following the big wipe-out.

Speaking about his new Florida paintings, Kobaslija could easily have been describing his Kesennuma series: “Their narratives develop over time — I know how to get there but I don’t want to know what will I find once I’m there. I understand the paintings through the act of making them, each piece individually or as a group, one in relation to the other.”

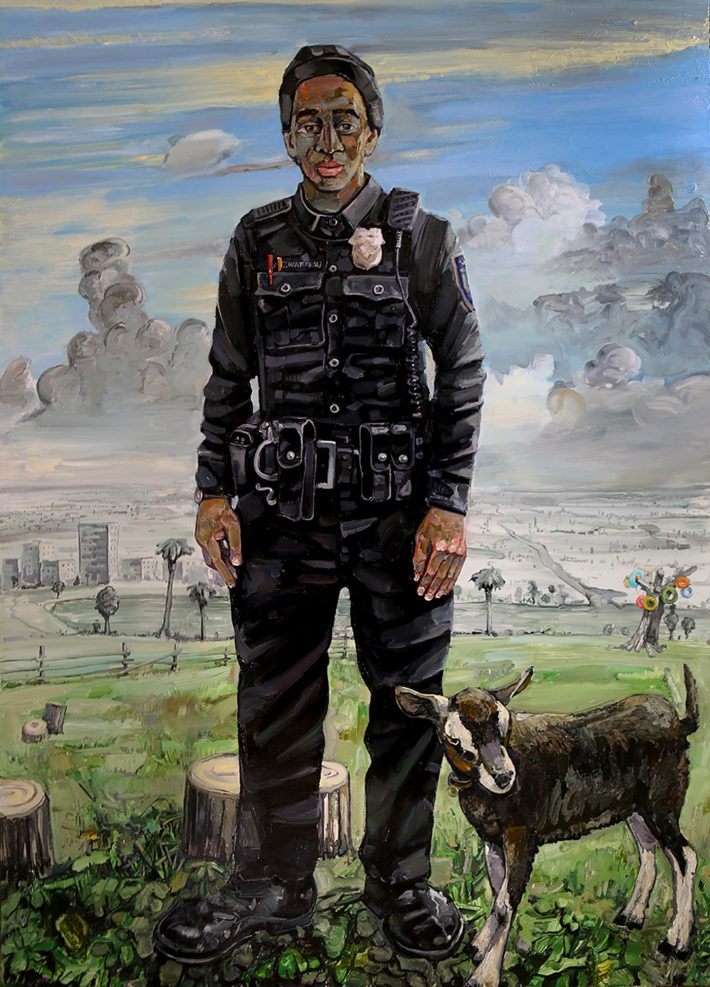

In “After Watteau II” (2018, oil on aluminum), for example, Kobaslija offers a portrait of a young police officer accompanied by a little goat; they stand on the outskirts of a city, which is visible in the distance on the left, while on the right, also in the distance, a tree is festooned with children’s colorful, inflatable swimming rings — a motif the artist returns to in a separate painting. Kobaslija’s policeman, with his big hands resting flat against his sides, gazes forward with a nonplussed look that seems to say, “This is me and here I am — at least for now.”

There is some irony in the picture’s title; despite its reference to the Rococo French painter’s “Pierrot” (c. 1718-19), a work famous for its theatrical air, “After Watteau II,” like all of the images in Kobaslija’s “Florida Diaries” series, is rather matter-of-fact. “This man’s face expresses a sense of decency and intelligence, but there is also a sense of alienation and a profound sadness in his eyes,” the artist noted.

That same tension between the quotidian and the grand or eloquent pulses through “River Patrol” (2018, oil on aluminum), another large work showing a uniformed policeman on horseback, his holster packed with a pistol and other gear. The tall buildings of a sprawling city are visible in the far distance, reminding viewers of the imposition of human civilization in a region whose natural phenomena, from the jaws of an alligator to the destructive force of hurricanes, are not easily tamed.

Literally and thematically, it is a picture of abundant fecundity, another one of Kobaslija’s quiet odes to whatever is enduring in the human spirit, in the guise of a portrait or a landscape. (In fact, often his landscapes turn out to be portraits of the natural world, with a discernible psychological edge. “What is the personality of this place?” they seem to ask, as though nature’s psyche were ripe for the probing.)

“Boy with Parrot” and “Phoenix, Water’s Edge” (both 2018, oil on aluminum) feature young children with their pets or plastic toys. More than the adults around them, they seem to be fully integrated into their surroundings. Their strange world of swamps, heat, bugs, and sinkholes — instinctively, they get it.

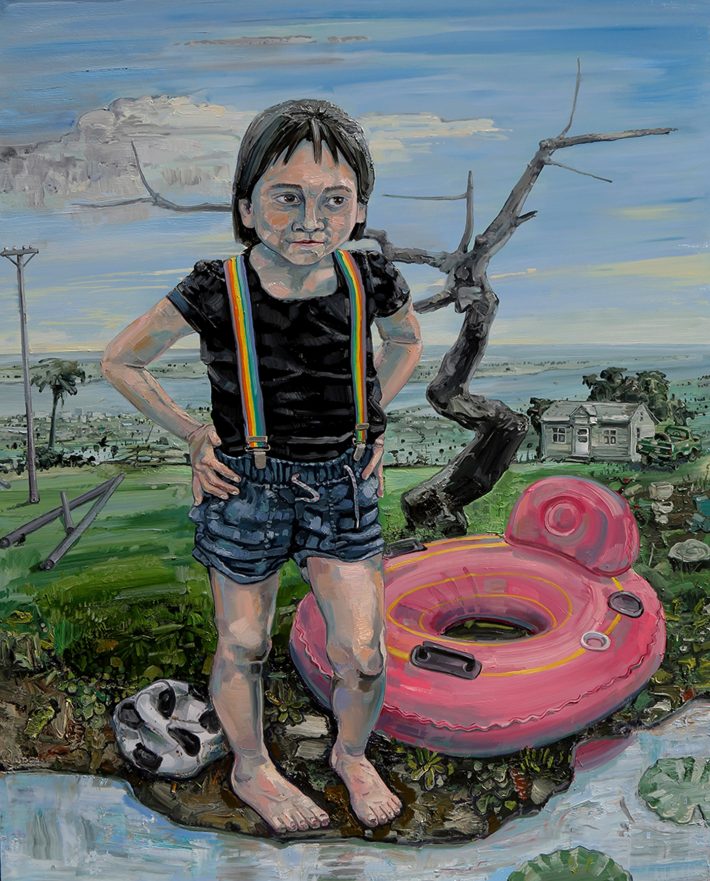

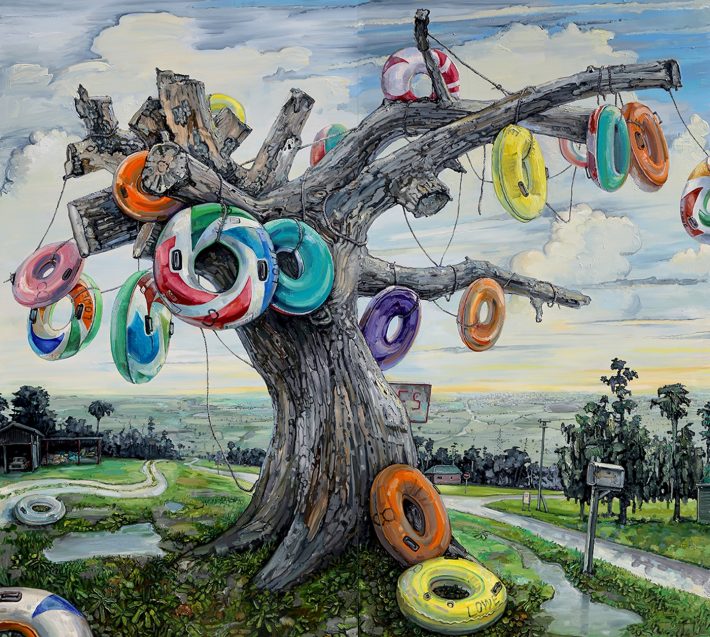

In Kobaslija’s pictures, such children are as much creatures of their peculiar habitat as they are its knowing custodians. In “Lowe’s Tubes, Ichetucknee” (2019, oil on aluminum), the artist pays tribute to their cheeky energy and to the surreal encounters between nature and human interlopers that catch his attention at every turn.

Amer Kobaslija, “Lowe’s Tubes, Ichetucknee” (2019), oil on aluminum, 96 x 108 inches (© Amer Kobaslija)

“I’ve always been interested in painting representationally,” Kobaslija said. “The visible world fascinates me — the way things appear. There is something extraordinary about the everyday or the banal that makes me want to look more closely, as if whatever might lie beneath the surface — the spirit of a place — may be revealed through the process of prolonged looking.”

As his new paintings suggest, Kobaslija has been looking at what’s essential in his subjects more attentively and pensively than ever, an exercise that may have turned out to be its own, most satisfying reward.

Amer Kobaslija: Florida Diaries continues at George Adams Gallery (531 West 26th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through June 1.