By John d’Addario via theadvocate.com

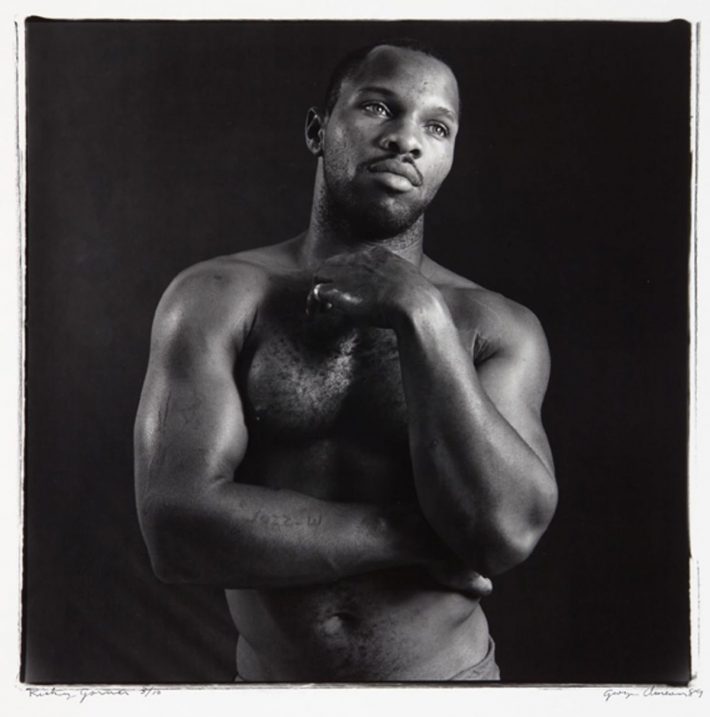

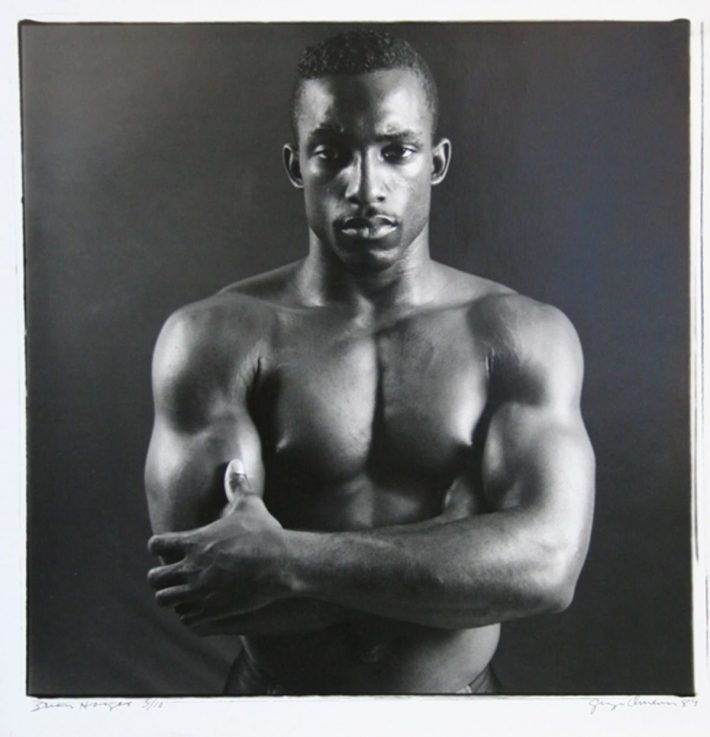

Brian Haynes, 1989 © George Dureau. Courtesy of the artist and Arthur Roger Gallery.

A new show at Arthur Roger Gallery provides an unprecedented opportunity to compare work by George Dureau and Robert Mapplethorpe, two of the most important figurative photographers of the 20th century.

In a just world, the two artists would enjoy equally significant reputations. But the general art historical line holds that the New Orleans-based Dureau’s photographs exist almost as a kind of footnote or sidebar to those of the more well-known Mapplethorpe, whose fame and notoriety have only increased since his death in 1989, while Dureau’s reputation has been mostly limited to local and specialized circles during the same period.

Mapplethorpe, for example, was the subject of a high-profile documentary as recently as 2016 — while Dureau’s death in 2014 did not even merit an obituary in The New York Times.

For his own part, Dureau was generous in his consideration of his younger and more famous contemporary. In a revealing 1991 interview with writer Jack Fritscher, Dureau minimized his own direct influence on Mapplethorpe’s work.

“Robert certainly never came to me to learn anything,” Dureau said. “Robert’s absorbency factor was great. He wasn’t a plagiarist so much as a Great White Hunter out stalking ideas.”

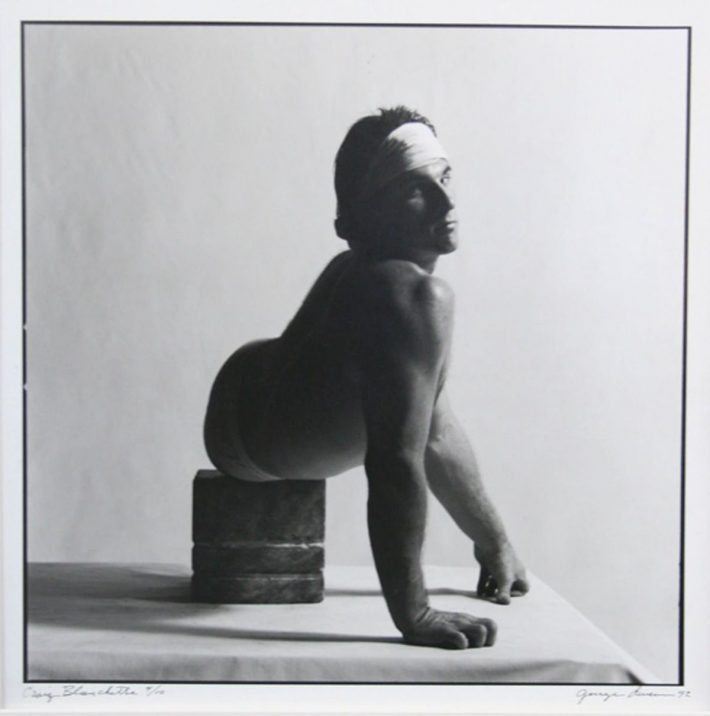

In that same interview, Dureau described his photographs as “family pictures,” capturing in a simple phrase the tenderness for his subjects that characterizes his portraits. By contrast, Mapplethorpe’s photographs are often marked by a more pronounced detachment and objectification.

The layout of the exhibition at Arthur Roger lets viewers observe those differences for themselves. The two artists literally face off against each other on opposite sides of the gallery, with individual photographs on each wall matched formally or compositionally with a counterpart on the other. It’s a clever way of inviting comparisons while giving each artist his own breathing room and a chance to have his work appreciated separately.

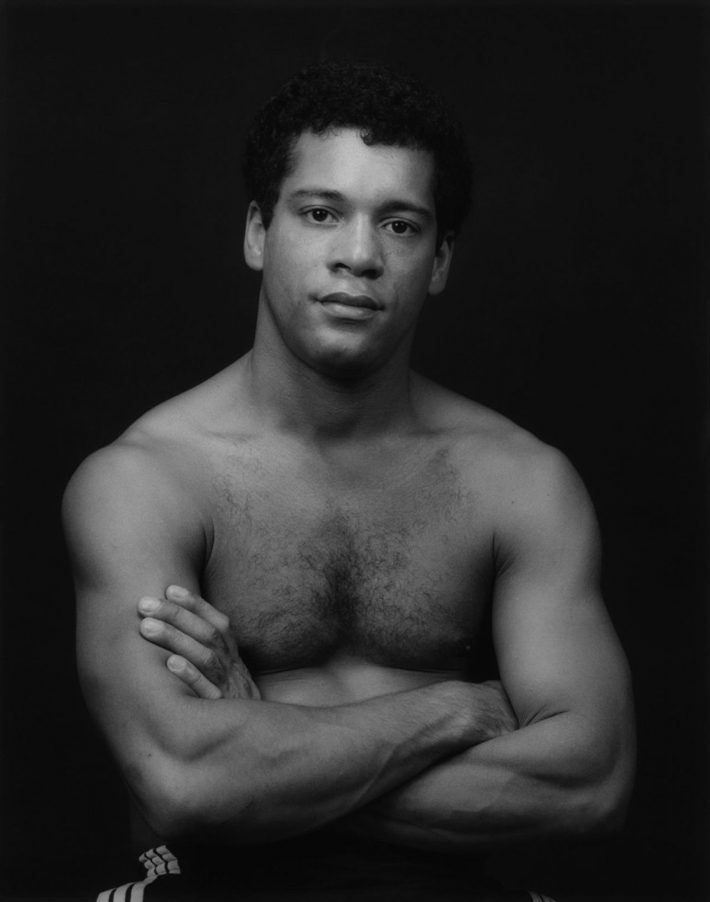

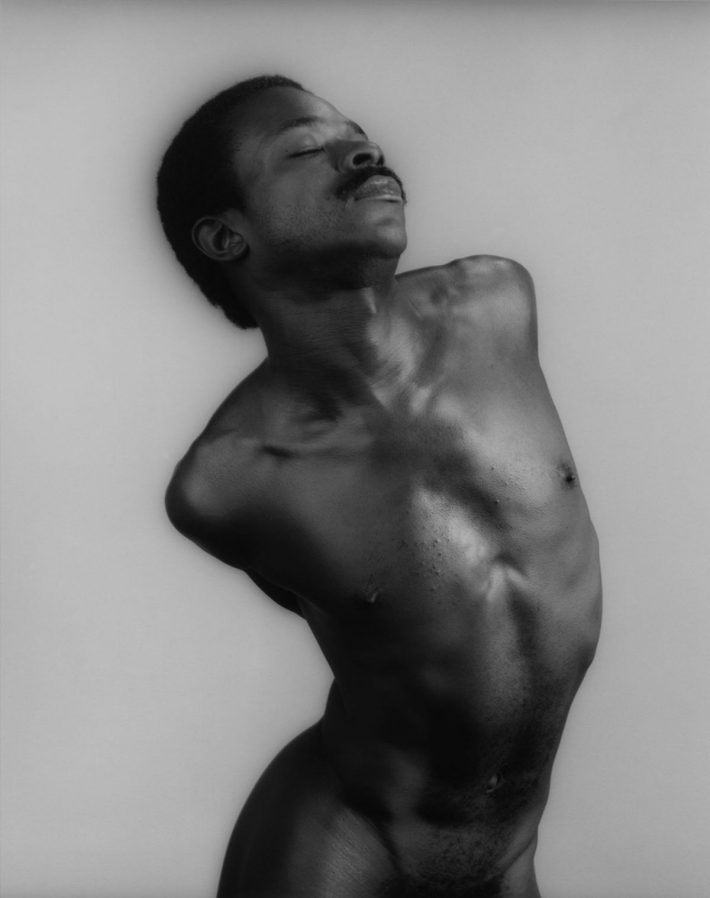

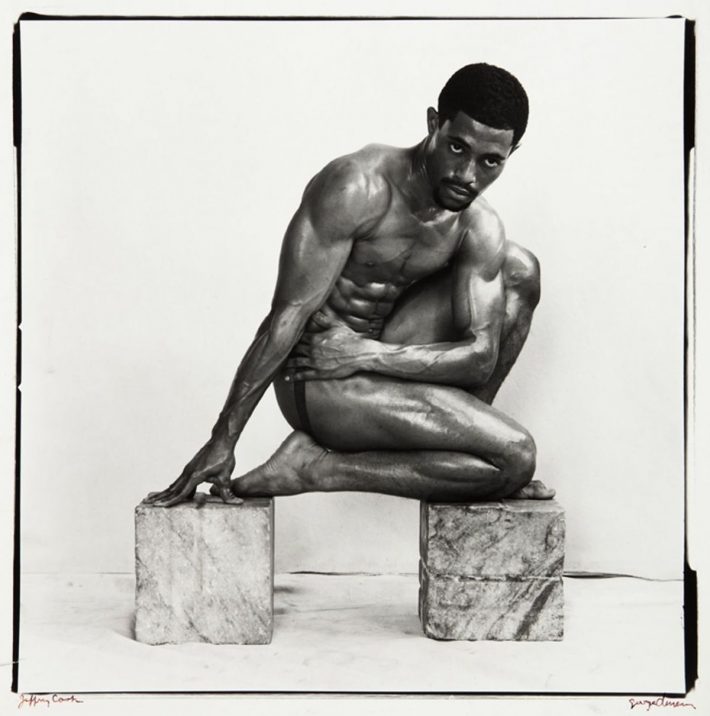

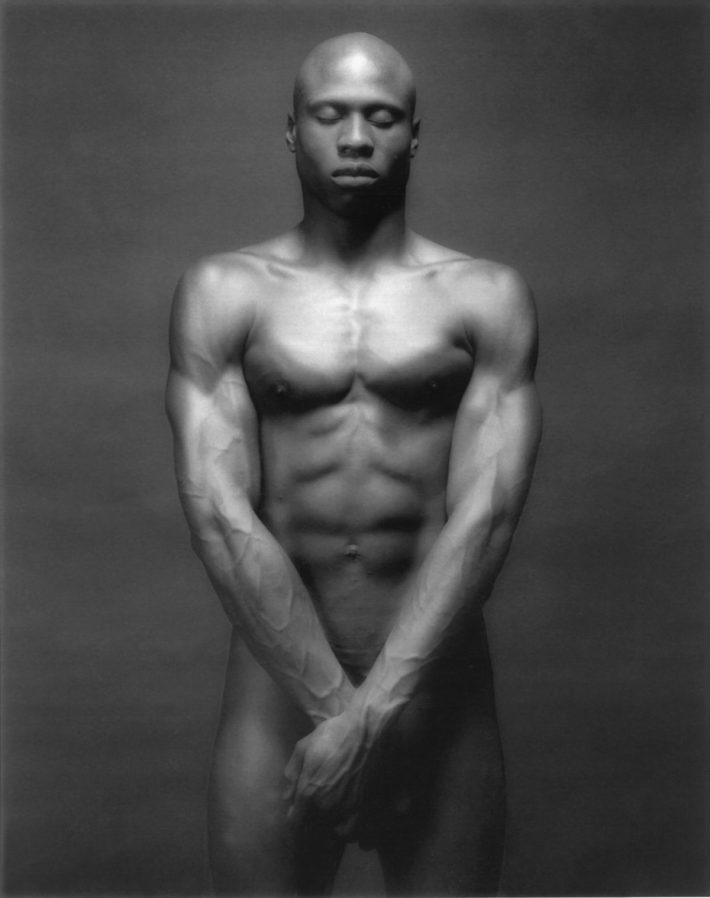

Even to those familiar with the two artists, the formal similarities in their work are initially more evident than the differences. Each photographs his subjects in black and white against monochromatic backgrounds. And of course the fact that both were white artists photographing mostly nude African-American men links Dureau and Mapplethorpe on a fundamental level. (While both artists photographed other subjects throughout their careers, the current show at Arthur Roger focuses exclusively on their portraits.)

But even from a distance — and even without knowing which artist is on which wall (for best effect, try not to look at the wall labels too closely when you enter the gallery) — the differences start to become apparent.

The lighting and contours in Dureau’s photographs are generally softer, for example, while Mapplethorpe’s use of high contrast creates sharper edges and more pronounced tonal differences.

A closer look reveals more differences. Most of Dureau’s models make eye contact with the photographer (and viewer); notably fewer of Mapplethorpe’s do. Mapplethorpe frequently crops his figures to concentrate (and sometimes fetishize) a particular body part; Dureau almost always depicts his models in their entirety.

And while Mapplethorpe’s photographs often feel like the artist is putting his models on display, Dureau’s give the impression that the artist is somehow caressing them. (Dureau put the difference more bluntly: “(Robert) makes his models look too available, whereas mine look like something dragged in off the street, which they were.”)

But in the center wall of the exhibition, which contains photographs by both artists, those differences become harder to identify. Instead, the show reveals itself to be less concerned with questions of how much Dureau might have influenced Mapplethorpe than showing how two artists worked in the same vernacular and formed a kind of dialogue through their images.