Laurence Ross looks at Tim Hailand’s exhibition at Arthur Roger Gallery, which blends contemporary portraits with historical patterned fabrics.

via pelicanbomb.com

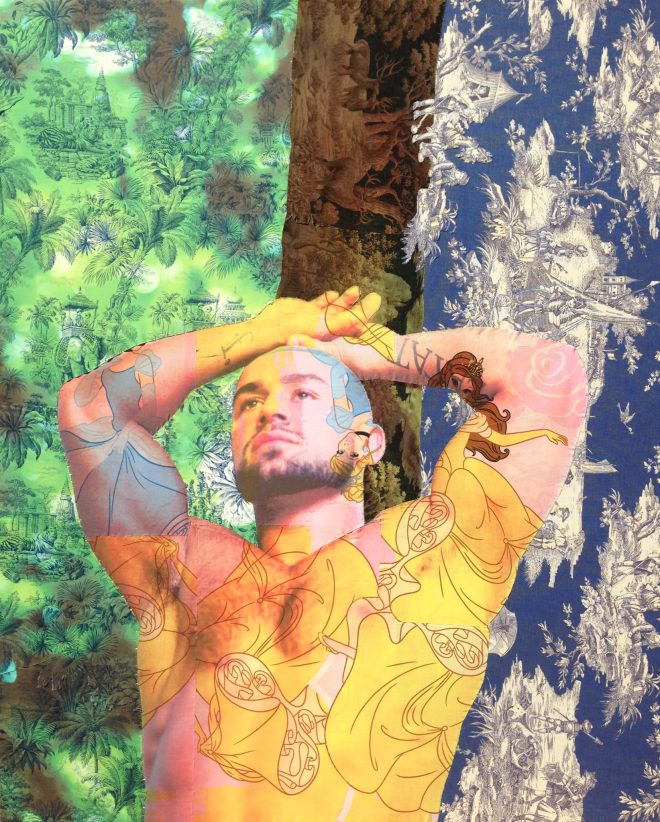

Tim Hailand, François Sagat Tuileries Tree Paris (on Disney Princess, blue tiger, and History of Air toile), 2016. Unique archival inkjet prints on patterned fabrics, gold thread. Courtesy the artist and Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans.

The term Toile de Jouy refers to a particular style of patterned textile, typically a neutral background overlaid with woodcut-style bucolic scenes of Rococo romance. Think of men and women lounging in billowed, ruffled sleeves, children playing in pantaloons, a musician playing the flute, or a farm animal at work. Roughly translated, Toile de Jouy means “canvas of joy.”

Considering these designs were often made into upholstery or wallpaper, the average contemporary viewer may be hard-pressed to feel joy; to be thrilled by a seat cushion or a parlor wall would be a rare ecstasy. However, artist Tim Hailand seems to be after something more complex than simple joy in his exhibition “Sister I’m a Poet,” currently on view at Arthur Roger Gallery. Using Toile de Jouy as inspiration and oftentimes as an artistic medium, Hailand prints photographic portraits on a wide range of textiles, some pieces using a single pattern while others use a number of fabrics stitched together with gold thread.

The first piece in the exhibit, titled Michel in Monet’s Greenhouse Giverny (on distressed Japanese garden toile), 2014, is a portrait of a young man printed on a Japanese garden toile. Though my mind quickly flits to ukiyo-e [floating world] woodcuts—and then to blue-stamped plateware—the patterns of this toile and the photographic overlay create a cognitive dissonance. The foliage doesn’t quite align, causing a rift in the overall coherence of the final image. The wide-leafed fronds of Monet’s greenhouse and the branches of a Japanese maple merge to create an entirely new scene. The figure of Michel is partially camouflaged, obscured. Perhaps, more accurately, layered. While the figure of Michel is unknown, the identity Hailand communicates with the piece is a complex one: a subject who has found himself betwixt two landscapes.

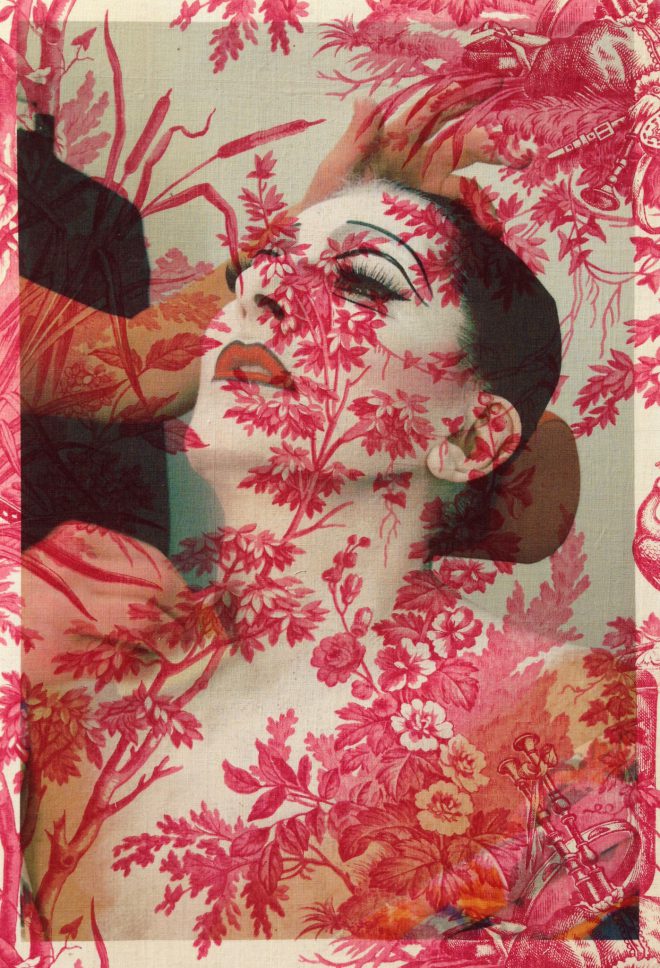

The inspiration for using toile as the backdrop for his photography came from Hailand’s 2012 residency in Giverny in Normandy, France. Though home to the gardens of Claude Monet, Hailand spent much of his time inside due to spring rains, in a bedroom decorated in red Toile de Jouy. Learning this after seeing “Sister I’m a Poet,” I am not surprised. The figures, many of whom seemed trapped behind a screen, are reminiscent of the nameless protagonist of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s most famous short story, “The Yellow Wallpaper,” from 1892. (In the story, a woman who is deemed “hysterical” is brought to the countryside to “recover” and ends up spending her days locked in a bedroom until the wallpaper drives her mad, ultimately causing her to see a mirror image of herself trying to escape from the patterns of the textile.) Considered one of the earliest pieces of American feminist literature, “The Yellow Wallpaper” is a cautionary tale of what might happen to a mind left under-stimulated and uninspired.

Tim Hailand, Marina Abramović Make-Up Basel (on vintage red peacock toile), 2016. Unique archival inkjet print on patterned fabric. Courtesy the artist and Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans.

In Hailand’s Demi Moore Hair and Tree Stump Los Angeles (on navy and beige floral toile), 2015, Moore’s eyes peer out at us from behind a heavy screen of navy and beige floral toile. Though the dark black of Moore’s hair is captivating, her naked skin looks bound by the bombastic Rococo flora. Amidst this topsy-turvy overgrowth, there is a romantic pair of lovers: a woman tossing out a coy ankle while her suitor plays a song on a bagpipe. The figures in the patterned fabric are enjoying the repose of courtship, and, left with just the images of the toile, we might also feel perfectly comfortable and therefore entirely bored. However, Moore is staring straight back at the viewer, her own photographic aura tinting the beige toile green, and coloring this piece as a portrait of envy. But is this the image of a woman envious of the couple’s romance of which she is not truly a part? Or is she, rather, envious of the viewer’s freedom from that grandiloquent Rococo landscape?

Hailand finds inspiration in textiles apart from the world of toile as well: fabrics printed with Easter bunnies, Dutch cows, or Disney princesses. In Wax Statue of Joan of Arc Rouen (on red and blue paisley print, Disney Princess, and Liberty prints), 2016, Joan and the silhouettes of other helmeted figures ascend ladders through layers of falling flowers. The figure of Joan of Arc contains a print of Disney princesses, confined within her shape. Here we see gender, strength, heroism, and identity at war. Though the arrow in her shoulder and the printed princess inside her breastplate suggest breaking out of a given identity is one serious struggle, Joan of Arc simultaneously seems to have escaped the confines of the tower or country house in which these other women of popular lore are kept. She is the hero climbing up the ladder, not Prince Charming, suggesting that our saving grace may come to us in unexpected ways.

We cannot choose our inspiration; we cannot choose what catches our eye. Ideas come in many guises, and we must be available—and open—to receive and recognize when we are being offered a new thought. Hailand seems to have seized the opportunity to advance his photography amidst what others may find a prison, to evolve his practice, to choose to reclaim a sense of joy in the quotidian. Of course, finding joy in the quotidian is anything but ordinary.