Essay from The Massachusetts Review, Spring 2011

Printed by the Studley Press, Dalton, Massachusetts

There are stories here, stories to be narrated by each of Whitfield Lovell’s spare renderings of humanity.

There are stories here, stories to be narrated by each of Whitfield Lovell’s spare renderings of humanity.

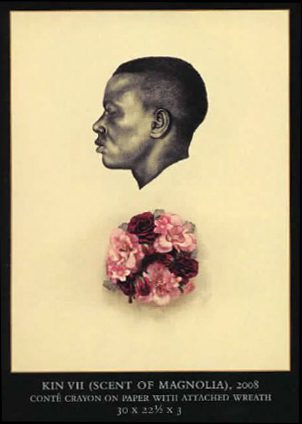

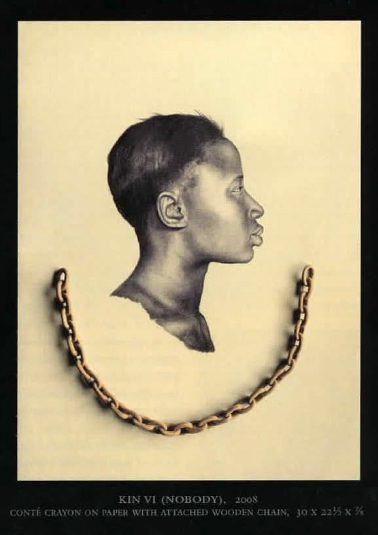

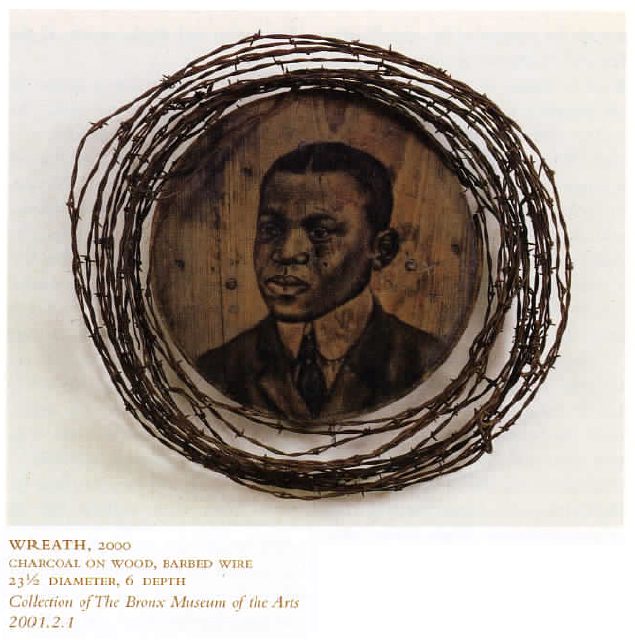

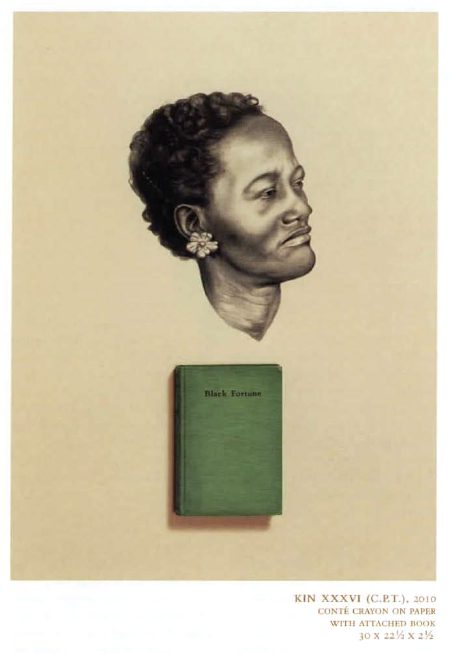

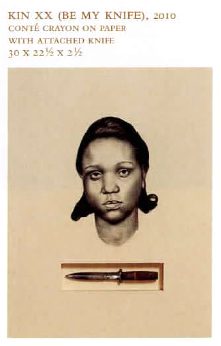

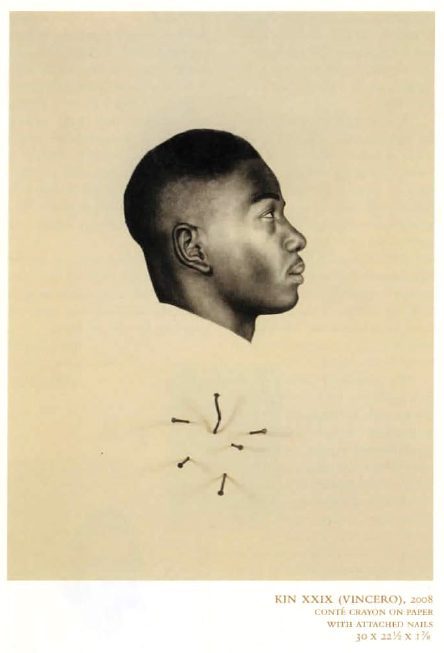

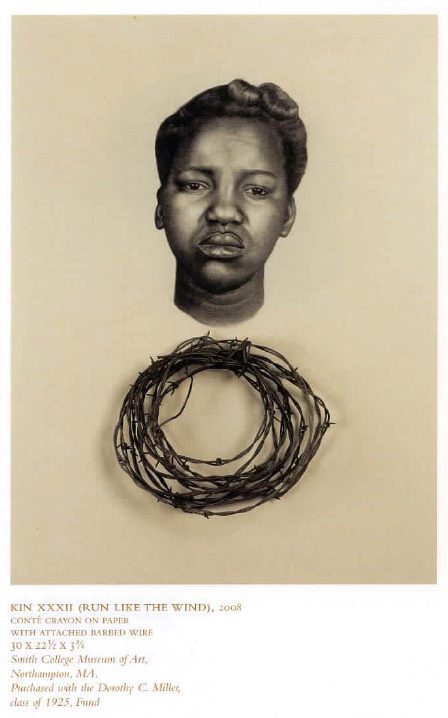

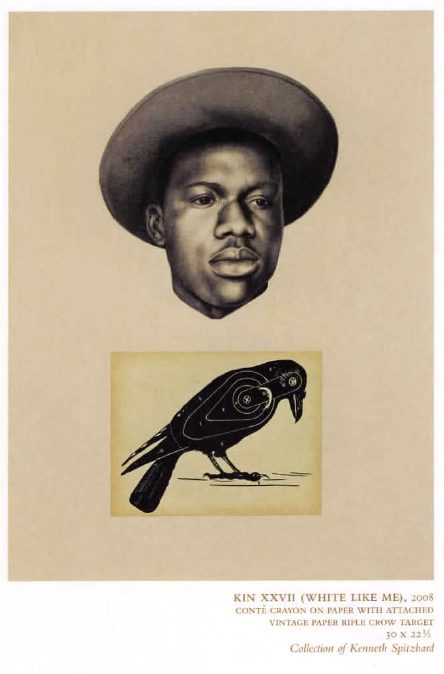

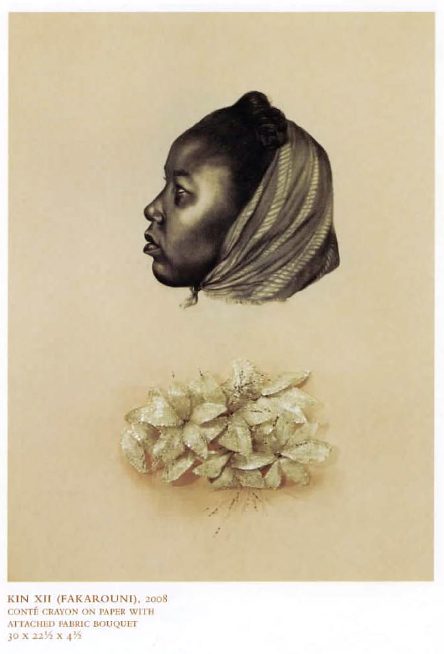

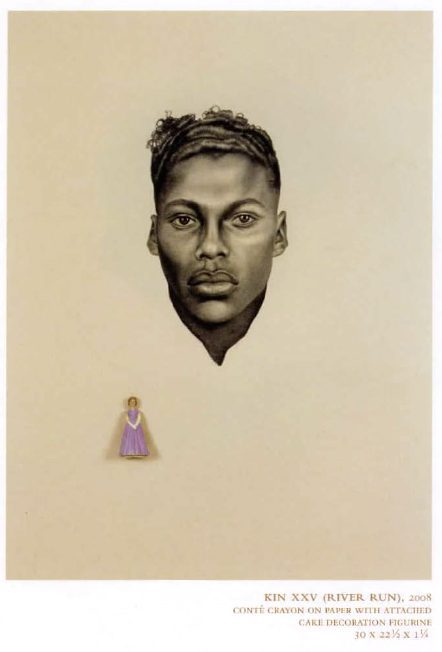

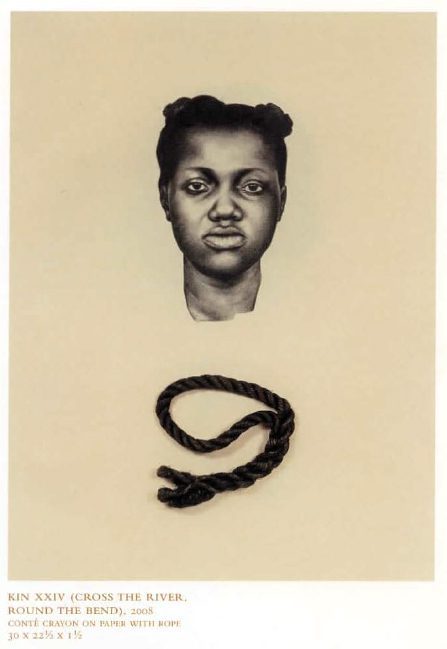

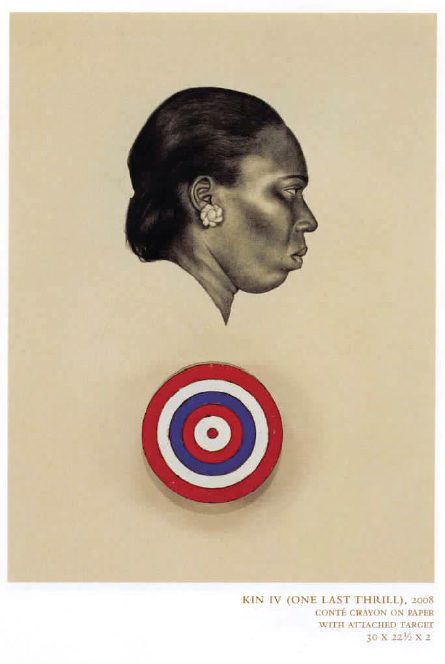

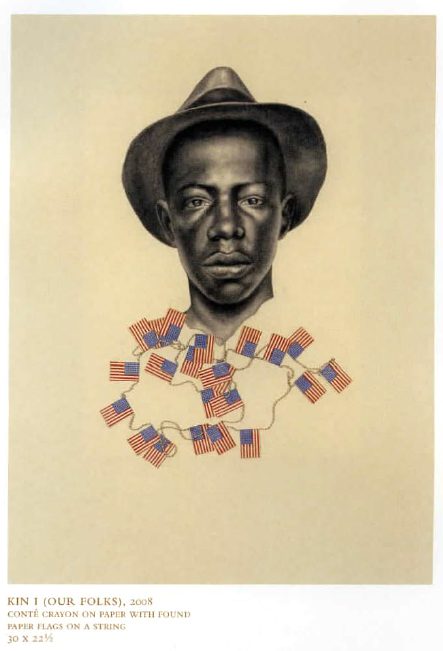

It is the use of juxtaposition that one might notice first – that each piece is composed of a charcoal or crayon drawing on a slate of wood or cream paper, and an artifact, a found object from everyday life (a figurine, a bit of rope, a chain, a knife, a fabric bouquet). The composition is clean, as if portrait and artifact are located near each other without abrasion or overlap.

The pairing of artifact and portrait doesn’t really create a sense of doubleness because the portrait is intended to be prominent. But there is tension there, a conversation between subject and object placed so carefully near each other. Proximity is contagion and the artifact insinuates itself on the portrait. Indeed the artifact becomes part of the subject’s body, marking the place where one might expect a shirt collar, apiece of jewelry, the outline of a chest. Localized and domesticated, the artifact’s randomness is exchanged for specificity, a result of the presence of these bold beautiful black faces.

The pairing of artifact and portrait doesn’t really create a sense of doubleness because the portrait is intended to be prominent. But there is tension there, a conversation between subject and object placed so carefully near each other. Proximity is contagion and the artifact insinuates itself on the portrait. Indeed the artifact becomes part of the subject’s body, marking the place where one might expect a shirt collar, apiece of jewelry, the outline of a chest. Localized and domesticated, the artifact’s randomness is exchanged for specificity, a result of the presence of these bold beautiful black faces.

And the subject is clarified by the artifact. Look, for example, at Kin VII (Scent of Magnolia): Are these flowers from his room, a private and unusual explosion of color? The flowers he gave to a date or the ones be brought to a funeral? We might pick up the title’s reference to Billie Holiday’s thick voice on “Strange Fruit” (“scent of magnolia sweet and fresh / the sudden smell of burning flesh”) which might lead to a more ominous reading – his killed body marked by a wreath – but it is unsatisfying to be so singular and definitive with this image. Because of the flowers, he is more a subject than an emblem; we can wonder if he loved pink and purple tones without ignoring the possibility of racist violence. Whatever the story, the flowers are a surprise, they interrupt the dominant narratives that might be ascribed to the profile of a black man of that age.

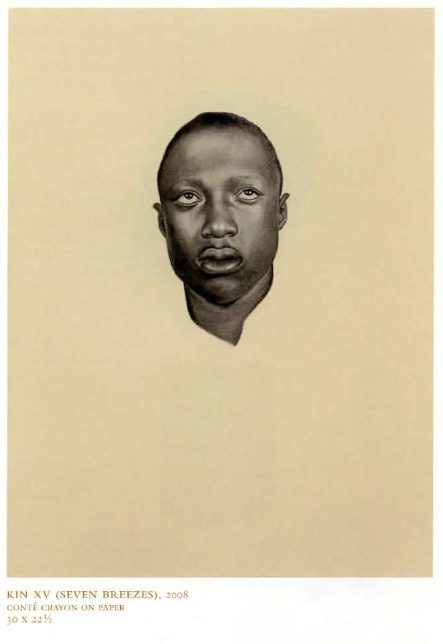

The foreboding is there in Lovell’s work – the chain, the barbed wire, the target, the rope – as it would be, often is, for a black person in the U.S., but it should not overwhelm the subject’s humanity. It is only part of their story. Lovell seems to aim tor a balance between the social or public meaning of a person (or object), and its intimacy, its human relevance. Where his earlier work created tableaux using full-bodied figures, the aesthetic of juxtaposition in these pieces is what evokes narrative, as if we are seeing the unfolding of a scene of human life, as if more and more of the image will manifest if you look long enough. (This is especially true of Lovell’s drawings that lack corresponding artifact, such as Kin [Seven Breezes].) The key is to let the unexpected be possible.

The power of the narrative turns on these bold beautiful black faces, which are stunning evidence of Lovell’s skill in drawing. The portraits were made from anonymous posed studio photographs found at flea markets or town archives (his earlier tableaux, for example, including shows like Whispers from the Walls and Sanctuary), as well as from identification photographs (his more recent work, especially Kin). In both cases, the portraits render their subjects in terrific clarity (the intensity in the eyes, the relaxedness around a mouth, the tautness of the curled hair). His use of shadow is astute, and the result is images of people who look like people – not symbols but people in the everyday, wary and resolute, alive. They look familiar to us even if it is rare to see black faces represented in such a studied, elegant way. Even with the images made from identification photographs, there is an intimacy, a sense of agency, as if the portrait reveals something particular about the ambition and ethic of the subject.

The power of the narrative turns on these bold beautiful black faces, which are stunning evidence of Lovell’s skill in drawing. The portraits were made from anonymous posed studio photographs found at flea markets or town archives (his earlier tableaux, for example, including shows like Whispers from the Walls and Sanctuary), as well as from identification photographs (his more recent work, especially Kin). In both cases, the portraits render their subjects in terrific clarity (the intensity in the eyes, the relaxedness around a mouth, the tautness of the curled hair). His use of shadow is astute, and the result is images of people who look like people – not symbols but people in the everyday, wary and resolute, alive. They look familiar to us even if it is rare to see black faces represented in such a studied, elegant way. Even with the images made from identification photographs, there is an intimacy, a sense of agency, as if the portrait reveals something particular about the ambition and ethic of the subject.

The artifacts, and their juxtaposition with the portraits, are a tribute to Lovell’s conceptual intelligence – that more than being a master of neoclassical portraiture, he is also gifted as a conceptual artist, able to work in a third dimension and to engage the principles of postmodernity (disparateness, disorder, multiplicity, ambivalence). But the clean of his juxtapositions seem to refuse the noisiness that is so often a part of modern art: these compositions are not put together violently, even if they sometimes suggest violence; they are not arranged harshly; even as what is harsh is part of the story they tell. There is an elegance here, a tone of delicacy, because after all, these are human lives and human lives are as delicate as they are anything else. Furthermore, the conceptual aspect of this work is not abstract. Instead, Lovell’s images rely on explicit concreteness – a portrait of a person who once lived on this earth, the presence of an object once used by a person who lived on this earth. These pieces are steeped in concreteness, as if to remind us that everyday life is full of fancy and whimsy and passion, desperation and displacement, all the elements of art.

Quiet is the prevailing quality of this work, not silence but quiet. The word “quiet” here is intended as a metaphor for the interior, for the full range of one’s inner life – one’s desires, ambitions, hungers, vulnerabilities, fears. The interior is hard to describe and even harder to represent, but it is potent in its ineffability and is essential to being human. The interior is full of motion and energy, is expressive and dynamic, which is why silence is not an appropriate synonym – silence is too loaded a term, too readily associated with the absence of motion or sound. Quiet is ravishing and wild.

Quiet is also antithetical to how we think about black culture, and by extension, black people. So much of the discourse of racial blackness imagines black people as public subjects with identities formed and articulated and resisted in public. (In fact, the notion of resistance, so important to black life, is tethered also to this notion of publicness.) Such blackness is dramatic, symbolic, never for its self, its own vagary, always representative and engaged with how it is imagined publicly. These characterizations are the legacy of racism and they become the common way we understand and represent blackness, a lingua franca.

The idea of quiet, then, can shift attention to what is interior. This shift can feel like a kind of heresy if the interior is thought of as apolitical or inexpressive, which it is not: one’s inner life is raucous and full of expression, if we can remember to distinguish the term “expressive” from the notion of public. Indeed the interior could be understood as the source of human action – that anything we do is shaped by the range of desires and capacities of our inner life.

This is the agency in Lovell’s pieces, the way that what is implied is a full range of human life: that we don’t know the subjects just by looking at them or noticing the artifacts. That their lives are wide open and possible, and they are more than familiar characterizations of victimization by or triumph over racism. For sure, the threat and violence of racism is one story, as is the grace and necessity of the fight. But what else is there to black humanity, these pieces seem to ask? The question is an invitation to imagine inner lives of the broadest terrain.

This is the agency in Lovell’s pieces, the way that what is implied is a full range of human life: that we don’t know the subjects just by looking at them or noticing the artifacts. That their lives are wide open and possible, and they are more than familiar characterizations of victimization by or triumph over racism. For sure, the threat and violence of racism is one story, as is the grace and necessity of the fight. But what else is there to black humanity, these pieces seem to ask? The question is an invitation to imagine inner lives of the broadest terrain.

What sustains this invitation is the spare quality of the composition, and the aesthetic of juxtaposition. Lovell’s work is pure visual poetry: slim images enjambed and aligned, meaning left open. Who is that woman, that man? What was she thinking then, and what was the taste she liked the most? Did she like words, or prefer the lilt of a soft piano? These questions are only askable if we remember these people are human beings, and whatever partial answers we might have for them are not supplied by thinking through the lens of publicness. They, these people, have interior lives that are largely inaccessible to us. Many critics have noted that Lovell’s pieces are haunting, which makes sense given how exposed and vulnerable these subjects are (exposed and vulnerable not just to violence but to life itself). But maybe they are also ghostly in the way that Avery Gordon uses the term – that ghosts are bodies of wild agency, not fully comprehensible to our social and political language.

What sustains this invitation is the spare quality of the composition, and the aesthetic of juxtaposition. Lovell’s work is pure visual poetry: slim images enjambed and aligned, meaning left open. Who is that woman, that man? What was she thinking then, and what was the taste she liked the most? Did she like words, or prefer the lilt of a soft piano? These questions are only askable if we remember these people are human beings, and whatever partial answers we might have for them are not supplied by thinking through the lens of publicness. They, these people, have interior lives that are largely inaccessible to us. Many critics have noted that Lovell’s pieces are haunting, which makes sense given how exposed and vulnerable these subjects are (exposed and vulnerable not just to violence but to life itself). But maybe they are also ghostly in the way that Avery Gordon uses the term – that ghosts are bodies of wild agency, not fully comprehensible to our social and political language.

It is a remarkable thing for a black artist working with black subjects (and in a visual medium) to restore humanity without being apolitical. It is remarkable, also, to make the argument that Lovell makes so well with his work – that what is black is at once particular and universal, familiar and unknowable.

Oh, the dignity here, the absence of spectacle, the clean of the poses. The grace and moral clarity. Oh, these images that are more than we know, more than we ever can know.

Kevin Quashie

Afro-American Studies

Smith College

All images appear courtesy of the artist & DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY except where otherwise noted