by Terrington Calas

New Orleans Art Review, September/October 2000

This essay was published in Arts Quarterly on the occasion of Robert Gordy’s retrospective at the New Orleans Museum of Art. We re-print it here, in edited form, as commentary on the recent exhibition of a selection of Gordy’s early works.

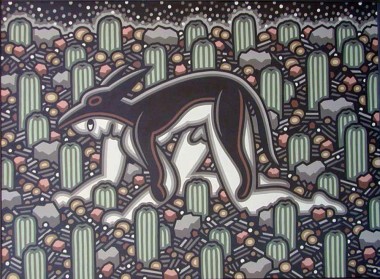

Robert Gordy. Desert Nights III, 1978. Acrylic on canvas, 53 x 72 inches

Robert Gordy is a quintessential visionary. A dreamer. An undauntable dweller in that violet-skied, chimerical world of aesthetic fantasy. Rarely has there been much attention given to this facet of his art; it seemed so latent over the years. But his 1981 survey, assembling twenty years of his paintings and drawings into a remarkable cohesive whole, tacitly proclaims that it is the principle facet and cannot be overlooked any longer.

For several years it had been something of a facile matter for observers to invoke, above all else, Gordy’s affinities with Cubist spatial structure. Yet in doing so they undermined meaning in his art in favor of pictorialization. The work’s own proficiency, as seen in countless one-man exhibitions, was the inspiration: those clean edged and stylized forms, those flawless color harmonies. They were so perfectly fashioned that too many of us skirted the challenging peek beneath their surface. After all, these pictures began to appear during the 1960’s reign of purist abstraction: “What you see is what you see.” But to look at Gordy’s leaping ladies and agitated mastiffs in that way was myopic, to say the least. The consequence was the erroneous impression that his art was purely formal, that it lacked content and – the ultimate trap – that, in keeping with late-modernist conventions, it hardly needed any. All of this rendered Gordy as a kind of southern Frank Stella gone figurative.

That, to my mind, he is not. And seeing his total oeuvre in a retrospective display verifies the opinion. A formalist, Stella-like Gordy would have made an art to be adored for its patent exquisiteness, for its cleverness, for its daring opacity. By contrast, what he did make from the outset was an art of psychological anxiety coupled with haunting, cryptic imagery and recurring sensuality. These are elements that reach back to early modernism, to that haven for artistic visionaries, to Symbolism. And so, while I can imagine few artists as stylistically individual as Gordy, it seems fitting to locate him in this tradition and to ponder his content (the meanings, the ideas) as a neo-symbolist content.

In 1979 a review in Artweek, on the occasion of two substantial Gordy shows in Texas, was impressed with how the work “dazzles the viewer with colorfully decorative intricacies,” how the figures “resemble notes on a sheet of music” and how – in River Bathers (1978) – “the black ground and jazzy landscape recall, despite Gordy’s protests, the stylization of art deco.” Of course, but what might that landscape suggest or, more directly, mean? Are we really intended to see only “decorative intricacies” and art deco stylizations? If that were so, Gordy’s art should swiftly be ushered to a wallpaper factory or, perhaps to the already weary New York repositories of the ariste-decorateurs, those MacConnells and Shapiros and Kushners.

Even the more insightful Hilton Kramer, in the New York Times, saw only part of Gordy’s achievement. He found the paintings appealing, but emphasized their “almost stenciled look” and the “impersonal architecture” that his forms effect. Kramer may likely have seen only a limited number of pictures, but upon any careful study they are hardly impersonal. He does, however, open one door, if only slightly to a further grasp of Gordy’s art. He notes that beyond “the patterning of its forms” is a “sensitivity of color-especially the grays, blacks, and earth colors, which are used with such subtlety.” “Sensitivity” of color, despite that term’s ambiguity, is essential to any art with symbolist tendencies. With Gordy it connotes color that is atmospheric, subjective, at times theatrical, often allusive of latent meaning and always sensuously beautiful. It is the color of Odilon Redon, of William Blake.

More significantly, perhaps, than symbolist color are the symbolist images which have figured conspicuously in Gordy’s iconography from the outset. They fairly sing through his orate surfaces.

Gordy’s exploration of pattern and surface beauty has been relentless, exhilarating. In the large major canvases, as well as in color ink drawings, he is revealed as a masterful heir of the French tradition of elegance and luxury in art – a tradition that, in modern times, saw Manet’s tables des cristaux et limons, Degas’ ballet and race-course pictures, Toulouse-Lautrec’s lush purples and art-nouveau sinuosity, Gauguin’s exoticism (both of color and imagery) and, above all, Matisse’s Luxe, calme, et volupte. Gordy embraces the tradition grandly. Yet despite the high decorative element in these works done prior to 1981 the urgent point is that Gordy’s neo-symbolism is undiminished.

In many of Robert Gordy’s works from this period anxiety and even pending violence are inevitably at hand; but there is another group of paintings, apparently affiliated with Matisse’s Luxe, calme, et volupte dictum: “an art of balance, of purity and serenity… an art which might be for every mental worker… like an appeasing influence, like a mental soother, something like a good armchair in which to rest from physical fatigue.” In a word, art as the supreme tonic.

For me, these two facets of Gordy’s work are distinct. In a sense, however, he weds them by using soothing decorative patterns to seduce us into a system of symbolist dramas that are anything but soothing. We are constantly tugged, in many of Gordy’s works from this period, both toward the meaning of their symbols and toward their inherent comeliness. Our interest is thus sustained. This atmosphere of tension between psychological disquiet and pictorial luxury creates a world removed from our own – a neo-symbolist world where a visionary’s dreams, no matter how unseemly, are realized.

In Gordy’s more Matissean pictures – those tableaux of sylvan landscapes populated by ideal nudes, palm trees and in some instances, geometrically stylized forms – the only conspicuous tensions occur between formal elements. Gordy’s mastery of design is used in the service of an overwhelming pastoral luxury. The ultimate Matissean dream. Gordy’s soft and rich colors help achieve this. So do his images restful or playful nudes, crisply contoured plants and architectural elements. All of these, moreover, are presented as visual metaphors, created suggestions of their identities. In this way they remain wholly Gordy’s images, reaching us in their grand meaning, yet residing in their own visionary universe.

All of Gordy’s paintings, of course, do not fit neatly into two groups. There are instances where the serenity of Luxe, calme, et volupte is absent, as well as any apparent psychological anxiety or where the anxiety seems purely sexual. Nonetheless, one overriding point can be submitted. It is the recurring use of the female nude. Time and again it serves as the emblem of a broad range of emotions: fear, malice, sensuality, utopian repose. The choice of the female is significant. Since it traditionally symbolizes the ideal form, it takes on a special intensity and effectiveness when subjected to the heights and depths of human psychology.

It is true also that Gordy’s neo-symbolist content is substantially effective even when, in certain color ink studies, the figure is not included. One splendid example is Study for to the North (1979). There are few works of such flawless pictorial design, which, at the same time, are so moving. By way of sheer compositional strategy and layers of color nuance, Gordy has created something close to an Arcadian paradise.

To be sure, his work is appreciably indebted to certain tenets of Cubism. A picture like this one, so systematically structured, would not be possible without it. And yet he is aware, as Braque and Picasso finally proved to themselves, that Cubism’s aesthetic lesson was far too limited, far too impersonal. It tended, in the words of Ortega y Gasset, “to dehumanize art, to see to it that the work of art is nothing but a work of art.”

In order to invigorate this formalism in his own work, Gordy looked to the symbolist-surrealist tradition. The outcome is the rich, multi-layered oeuvre we see in Robert Gordy’s work through 1981.