The Arthur Roger Gallery is pleased to feature the artwork of recent NOCCA graduate Leonard Galmon. Please contact the gallery regarding availability of the following works.

Following is a recent article about the artist from The Times-Picayune.

“A 13-year-old mother, a murdered father and a scholarship to Yale,” The Times-Picayune

By Danielle Dreilinger via NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune

May 23, 2014

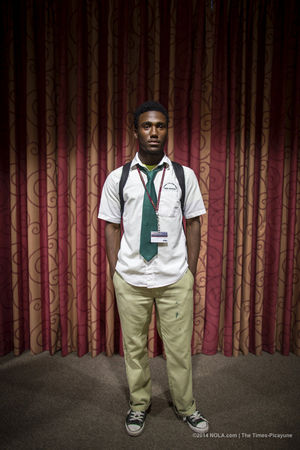

Leonard Galmon, a NOCCA and Cohen College Prep senior who grew up around the C.J. Peete housing projects, will be going to Yale next year. He was photographed near one of his pieces hanging on a hallway wall at the end-of-year art show at NOCCA on Thursday, May 8, 2014. (Photo by Chris Granger, Nola.com | The Times-Picayune)

Leonard Galmon’s favorite artwork from his senior year, his first and only year at New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, was on display this spring at the Contemporary Arts Center. The three-dimensional painting-collage shows a young man in a gray hoodie, his shoulders hunched, looking back at the viewer. On the ground behind him is a gun. The young man’s shadow stretches over it.

To the artist, it’s a simple exhortation: Walk away from trouble.

If Leonard, 17, had grown up in different circumstances, there are things that would have come to him as a matter of course. Enough food for the whole family, all month long. A good school. An art class with proper supplies. For most of his life, he had none of these things. What he had was a family that loved him, a library, a school, an art class. He made the most of them, until he at last saw a way to something more.

Leonard Galmon — artist, oldest of six children, son of a 13-year-old girl and a murdered drug dealer, veteran of one of the worst schools in New Orleans — is going to Yale.

Leonard Galmon, back center, a NOCCA and Cohen College Prep senior who grew up around the C.J. Peete housing projects, will be going to Yale next year. He walks with his best friend DeRondice Reese at the end-of-year art show at NOCCA on Thursday, May 8, 2014. (Photo by Chris Granger, Nola.com | The Times-Picayune)

When he wrote his college essay, “We were told to think about stability and instability.” Leonard said. “I got to thinking about my life. It hasn’t ever been stable.”

He doesn’t remember his father, Leonard Morgan. Though “he wasn’t exactly a model citizen,” as Leonard puts it — he sold drugs — he was liked by everyone except Leonard’s great-grandmother. She wanted to have him arrested when Morgan, 19, got her very young granddaughter, Wanda, pregnant. Like his son, Morgan was quiet but smiled a lot. He would watch the boy while Wanda was at high school. When Leonard was 4, his father was killed on the streets of the Magnolia public housing development, on a bright, sunny day with hundreds of people around.

When speaking of those days, Leonard unconsciously slips into the second person.

You always ran out of food stamps before the end of the month. Sometimes you came home to find the electricity turned off. Sometimes you bunked with friends and family. You never had any money of your own. If you found a $20 on the street, you brought it right home for the family.

As the oldest child, Leonard cooked and helped with homework, filling, in a child’s way, the role of the head of the household. “Life wasn’t easy, but I always knew at least one other kid, someone else, who had it worse,” he said. “I don’t want people feeling sorry for me.”

Occasionally he wondered whether stealing or dealing might make sense. The drug dealers were surrogate fathers in a way, maintainers of order and community. They’d tell your mom if you misbehaved and give you a dollar to get something at the store.

“Your parents always told you it was a bad thing — don’t do this, don’t do that — but sometimes your parents were the people doing these things,” Leonard said. “It felt very normal. Now, I know that’s not normal.”

His uncle, Alfred Galmon, remembers standing, one nephew in either arm — Leonard, 4, and Joseph, 2 — holding them up to see their father’s casket. Galmon knew he’d have to be their father figure now.

It didn’t work out that way. Galmon said he made mistakes for many years, chose the wrong route. Leonard said that for most of his life, his uncle wasn’t the best role model.

But he did teach Leonard how to draw.

Leonard Galmon, center, a NOCCA and Cohen College Prep senior who grew up around the C.J. Peete housing projects, will be going to Yale next year. He walks with his best friend DeRondice Reese, right, at the end-of-year art show at NOCCA on Thursday, May 8, 2014. (Photo by Chris Granger, Nola.com | The Times-Picayune)

For 9-year-old Leonard, Hurricane Katrina was an adventure: leaving their building when it started to shake, the sight of the building afterwards with its wall ripped off, the night they slept on the Claiborne Avenue bridge, the walk across to the West Bank pushing the youngest, a newborn, in a shopping basket.

Then it was a blessing. “I know Katrina was, like, a really bad thing. But it opened my eyes to a lot of stuff. I realized the world was much bigger than New Orleans,” he said.

In Houston, the young black ex-pat from New Orleans made his first non-black friend, a Hispanic boy. He began reading three or four books a week; the family called him Novelhead. He started to think about his future. “I became very optimistic. I believe people can do whatever they want. I always knew I was going to do something. I just never knew what.”

The promise of urban education is that a good school can change the trajectory of a child’s life. Professional educators, say reformers, can provide the crucial assistance for students who want to go far beyond what their parents accomplished, students whose parents desperately want them to go to college but sometimes haven’t been able to help with their homework for years. Reformers hope a good school can create a road map to reach dreams, like the ones Leonard was beginning to have.

Leonard came back to New Orleans and enrolled in one of the worst schools in the city.

—

To Leonard’s understanding, the family returned to town a few weeks after classes began for his freshman year. Many schools were full. Walter L. Cohen High still had room, however, and it was right down the street from their home. It also gave students only a 38 percent chance of graduating in four years. The only city school with a lower grade on the state’s report card had closed over the summer.

“It wasn’t a good school at all. My first day there was, like, a riot,” he said. Sometimes there was no permanent teacher, just a succession of substitutes. Sometimes he had to teach himself the material. There were no advanced classes. Cohen High got smaller each year as the state Recovery School District moved towards closing it, and remained an F school.

As if to add insult to injury, in 2012 a new charter school opened upstairs: Cohen College Prep. Its staff painted the dingy walls a clean, bright white and plastered them with college pennants.

Downstairs at Leonard’s school, Cohen High, some of the teachers were good. “Obviously I learned at the school because I didn’t just become smart this year,” Leonard said. But “I probably could have been way smarter if I had gone to a real high school. That school didn’t feel real. We played around a lot.”

Nonetheless, he stayed. Maybe he needed some stability after those unstable years and the Katrina disruption. He’d become shy. He stayed even though the family moved farther away to the 9th Ward, a one-hour, 45-minute commute.

He thought about applying to NOCCA at the end of freshman year, for writing, but found he’d missed the deadline. Instead of going to NOCCA for his sophomore year, he joined the Cohen High art class.

It took place in a cinderblock room cluttered with desks, with one window and one easel that the teacher brought from home. Only five or six kids wanted to take the class. There weren’t a lot of assignments. It wasn’t a very serious endeavor.

The teacher gave Leonard paint. He picked up a brush. The world unfolded before his eyes. His first painting was chosen for a Contemporary Arts Center youth exhibit.

During the summer after his sophomore year, he sat in his new room at home — the first he’d ever had to himself, after living seven people in a shotgun — and drew faces over and over.

—

All the upheaval in New Orleans public education since Katrina — the state takeover of 80 percent of the city’s schools, the extensive school closures that rend holes in a neighborhood and in people’s memories, the charters that come and go, the long bus rides — has a goal: a better future for the children. Leonard would certainly have graduated from Cohen and probably gone to some college or another. But the new system is supposed to provide more. It’s supposed to grasp the Leonards of the world like an arrow in a bow, to point them at their target, to pull back and let fly.

At the last possible moment, in junior year, Leonard identified his target. Cohen High “was comfortable. But college — I needed to go to college,” he said, and “I knew I would need a lot of help.” Of his three art-class friends, all seniors, one was going to Southern University in Baton Rouge, one possibly to Delgado Community College, the third to work.

Leonard decided to switch schools, twice over. He applied to NOCCA’s half-day art program for his senior year. And though some of his Cohen High classmates felt animosity toward Cohen College Prep, the charter they thought was squeezing them out, Leonard thought the newer school would split the difference: a strong college focus, but in the same building. He thought it would be a way to change without changing too much.

Everything changed.

Leonard Galmon, a NOCCA and Cohen College Prep senior who grew up around the C.J. Peete housing projects, will be going to Yale next year. He was photographed at a reception at the end-of-year art show at NOCCA on Thursday, May 8, 2014. (Photo by Chris Granger, Nola.com | The Times-Picayune)

The Cohen College Prep counselors had him apply to top schools, schools he’d never imagined: Wesleyan, Brown. Yale chose him, and he chose Yale. “That’s crazy. I was in denial — I couldn’t believe it at first,” he said. Above that, he was one of only 26 of 5,500 applicants to win a Ron Brown Scholarship, which provides extra money plus support to keep promising future black leaders on track.

Leonard isn’t really sure why all these good things came to him. Sure, he had the highest ACT score of any student in either Cohen High or Cohen College Prep: a 28 out of 36 maximum, putting him in the 90th percentile. “I worked hard. I never feel like I work as hard as other people, though,” he said. “I’ve never considered myself an over-achiever.”

Sitting on the floor of a storage closet at NOCCA, he paged through some of the pieces he made this year. His descriptions are peppered with the word “first”: his first screenprint, his first time painting in oils, his first sculpture, first photography class, first woodcut. The first day of class, he swallowed hard and pinned up his work to be critiqued, certain he wasn’t very good.

There’s a picture he made this spring of his neighborhood, a piece he singed around the edges, juxtaposing disaster and recovery. He regrets he didn’t make it as elaborate as he envisioned, but at the time he had to visit Yale and Tufts. There are still lifes from the levee where he went on a class field trip.

There are assignments he took literally, like the one to make a self-portrait of himself without a head. In that work, Leonard sits in his favorite armchair, wearing his favorite black Converse high-top sneakers, surrounded by stacks of his favorite books (lots of Stephen King) plus some books he hasn’t read yet but wants to — and no head. Several classmates had more creative interpretations of the assignment, he said.

Now he’s trying to convey messages with his work. Was it successful, the piece on layers of transparent plastic, with a United States flag and a politician smirking and extending his hand? Even with the hoodie-and-gun piece, one viewer thought the man had shot someone and dropped the gun.

If they don’t work, that’s OK. “I can always appreciate that I tried it. I can learn from my mistakes,” Leonard said. “I don’t know what I can or can’t do.”

His NOCCA classmates motivated him. Some of them have found their creative voice, he said, but he hasn’t. When he compares his work to theirs, “I’m good, but I’m not the best. I like that. I like still having a way to go.”

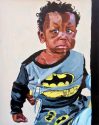

But there is a throughline Leonard doesn’t see in his work: the extraordinary faces, the skin mottled in red paint, greens, blues, unlikely elements carefully put together to seem not only natural but inevitable.

He said he already knew how to make art. He just needed to be shown how. All he needed were the ideas, the techniques, the tools, opportunity, guidance.

Leonard Galmon, center, a NOCCA and Cohen College Prep senior who grew up around the C.J. Peete housing projects, will be going to Yale next year. He talks with the visual arts chair, Mary Jane Parker, at the end-of-year art show at NOCCA on Thursday, May 8, 2014. Parker was telling Galmon that an administrator at NOCCA wanted to buy a piece of his art. One of Galmon’s pieces is to the far right on the wall. (Photo by Chris Granger, Nola.com | The Times-Picayune)

At the NOCCA year-end art show, almost everyone shows off their own pictures to their family. Leonard pointed out his new friends’ work. He moved easily in the halls, in the beautiful, professional environment — soaring ceilings, skylights, windows, printing equipment, tall sturdy easels — and the multiracial crowd, many members wearing uniforms from the region’s most elite public and private schools. It was easier to make friends at NOCCA, Leonard said, because he could always go up and start a conversation with anyone about art.

Leonard’s artwork is filled with his siblings. They sometimes fall asleep in his room. In one piece, a younger boy hunches over his Christmas scooter, scowling. His sister sleeps, sucking her thumb. His youngest sibling’s stuffed tiger sits on a chair. Timothy daydreams under a tree. Joseph walks away from a gun.

His family knows he’s going somewhere they can’t really imagine. “I’m 38, and I’ve never been around nobody who went to no Yale,” said Galmon, the uncle, shaking his head. “Never thought I’d see that … Yale. That four-letter word means a lot.”

He’s walking away. But they don’t see it as Leonard leaving them behind. He’s their surrogate dad, their role model, their pride.

“As long as I’m standing, I’m going to push him, because his success is my success, too,” Galmon said. He wishes Leonard’s father “were still here to see this. This would have been the ultimate happiness for him.”

Leonard thinks about his father a lot. As he takes his next steps to Connecticut, to art and to whatever comes beyond the target, his father’s story is never far, always there to consider at a quiet moment.

He said, “I’m just wondering about what kind of man I will be.“

![Leonard Galmon Untitled 1, 2014 Acrylic on paper 18 x 24 inches 23 1/2 x 29 inches (framed) [SOLD]](https://arthurrogergallery.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Untitled_1-167x125.jpg)

![Leonard Galmon Untitled 3, 2014 Acrylic on paper 24 x 18 inches 29 x 23 1/2 inches (framed) [SOLD]](https://arthurrogergallery.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Untitled_3-95x125.jpg)

![Leonard Galmon Untitled 6, 2014 Acrylic on paper 24 x 18 inches 29 x 23 1/2 inches (framed) [SOLD]](https://arthurrogergallery.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Untitled_6-95x125.jpg)