George Dureau. Ernest Beasley, n/d. Vintage silver gelatin print, 20 x 16 inches

By Terrington Calas

George Dureau Paintings, Drawings, and Photographs in Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA.

You enter the George Dureau exhibition expecting the celebrated interpreter of the human form, an artist who in his paintings, drawings and photography transforms the figure, even when physically compromised, into a thing of exalted beauty. You leave with that impression confirmed, but with another: an impression of timeless technical ingenuity that transcends mere talent, and, more important, a genuinely moving density of meaning.

Dureau is a figurative master. Our own. A legendary artist whose gifts we in New Orleans sometimes take for granted, or perhaps forget. And legend has a way of simplifying artists, abridging their achievements into one or two word slogans: timeless draughtsman, ground-breaking photographer. Dureau’s art is hardly so simple a matter. The handsome presentation now at the Arthur Roger Gallery is a reminder of a richness and complexity that is too seldom remarked.

The question of draftsmanship is an obvious first consideration. In keeping with his classical propensity, Dureau is always drawing. But, as with everything he does, the method is singular. Chiefly, he employs the Beaux Arts favorite, charcoal – frequently on canvas, with augmentations of oil wash, conspicuous erasures, and intermittent white heightening. One can see this in two untitled figure drawings from 1977, fantasy groups in which the artist appears as a satyr. The approach is distantly related to traditional grisaille, but with a modern restlessness suggestive of a work constantly in progress.

Dureau’s basic technique follows the Michelangelo-Rubens-Delacroix tradition, characterized by linear verve. It is the kind of drawing that relishes its subject, but at the same time asserts an autonomous presence. Dureau’s own line is peculiarly sinuous, searching; and it tends to romanticize the figure while enunciating it. In SelfPortrait with Camera, every curve is accentuated. And despite his familiar Manet-like streamlining of form, certain details are coddled: strands of hair that coil barely and idealistically, highlights on cheek and forehead that, somehow, both build and stylize shape.

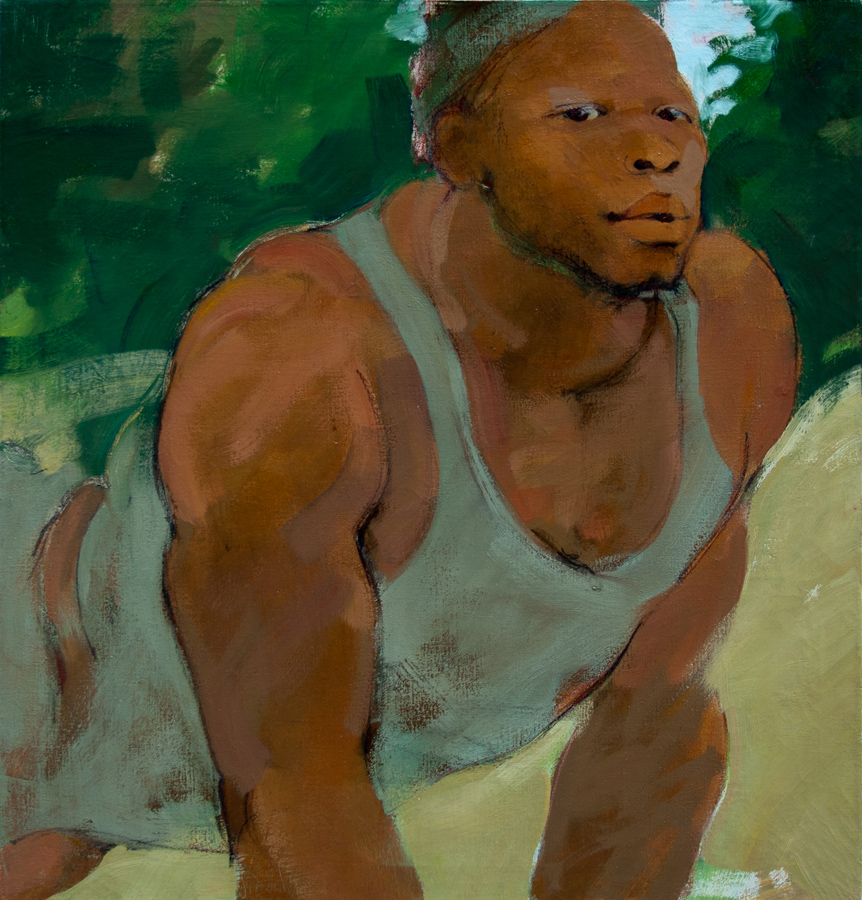

George Dureau. Elliot Lewis, 1972. Oil on canvas, 24 x 22 inches.

George Dureau. Self-portrait with Camera, 1979. Charcoal on canvas, 24 x 19.75 inches.

This romanticizing of the figure is manifest also in Dureau’s photographs. And to dramatic effect. His manipulation of chiaroscuro- at times approaching a tenebrist blackness- is a means of editing and refining. a composition. In most instances, you glimpse his models first as near-silhouettes: light against dark or dark against light. In Dureau’s hands, these value extremes coax a figure into an efficient, grace-immersed form. Contours are burnished, mid-tones minimized. As a consequence, his subjects -no matter their pedigree or physical condition-assume a certain stature. Many are eroticized; all are ennobled.The photographs are portraits. Dureau has often made a point of emphasizing this. Not mere documents, but portraits. And, despite their considerable polish, they are also essentially realist -or Realist, in proper allusion to the 19th century movement. He is after the penetration of humanness. And further: the amplifying of human dignity.

What drives him, it would seem, is an unaffected regard for the individual. You also sense an intuitive grasp of our common frailty and of the human crucible. A good example is the vintage print Ernest Beasley, an image of staggering power. The spatial structure of this piece is so flawlessly conceived that it grabs immediate notice. It is a masterpiece of tone-on-tone composing: a white shirt visually blending into a pale background, deep complexion blending into dark trousers. Fascinating bowed shapes and subtle gray striations are the result.

But, of course, what really matters here is the figure. This is not one of Dureau’s better-known nudes. He pictures a very stout man against a peeling clapboard wall, hands in pockets, leaning slightly to one side, and looking intently at the viewer. Intently and insistently, with an inexplicable expression. It could signify skepticism, or apprehension, perhaps a measure of contempt. It certainly is not vulnerability. Beasley’s eyes and the tum of his mouth refute the possibility. So does his pose. He is far from passive, and scarcely the victim that society might seek to make him. Dureau implies a certain heroism. What he has done, while evincing the man’s unmistakable heedfulness, is to render a fuller, more complex personality. Simultaneously, he discloses his own emotional affinity.

This personal regard runs through all of Dureau’s photographic work. And you feel no doubt of its validity. This is true in spite of his extraordinary formal control; and, notably, in spite of his range of subjects. The photographs constitute an abiding solace for us -an assurance that human compassion, even in our unquiet world, still exists.

Dureau is the least self-conscious of painters. He simply paints. Or, rather, that is how it often seems. He is famous for his charismatic touch: a racily fluent style of wide, slathering brush strokes and tonically unorthodox color. It is an approach that evokes bravura moments in painting as far-reaching as a suavely limned shirtsleeve by Manet to a de Kooning landscape. Lush pigment that has the look of just falling inevitably into place. The effect can be breathtaking. And no one does this better than Dureau.. And, not surprisingly, we tend to translate the apparent ease as painterly candor.

In fact, he is fully aware of his style, and savors it. He is aware of the rough-edged drag of certain brushstrokes. It is Dureau’s own version of traditional scumbling, an eye-grabbing riff he has used for decades. At Arthur Roger, this is notably evident in two early portraits, Ronnie Crawford and Elliot Lewis. You can see it in the way he depicts sand spilling across Crawford’s arm, and in the way he highlights the shoulder and chest with lashes of abrupt, semi-opaque, pale color.

Another recurring maneuver is pentimento, the deliberate favoring of “corrections”- over-painting that reveals traces of preliminary layers. This last is especially tough to pull off. And Dureau, again, makes it his own. In Elliot Lewis, a basically warm painting of golden ochre and venetian red, there are modest filterings of cobalt blue near the arm, around the hand. And, at key contours of the figure, he leaves charcoal edges unpainted.

Such piquant technical conceits lend an irresistible -and timeless-freshness to Dureau’s painting. The manner feels unbridled, reflexive, and at the same time, masterfully finessed. It conjures early modem painterliness, especially that of Manet -one of his heroes. It is the method of a consummate stylist. This is undeniable. But that is precisely half of his achievement as a painter.

George Dureau. Ronnie Crawford, 1977. Oil on canvas, 30 x 30 inches

What makes Dureau our finest figurative painter is his much is made conspicuous -only an occasional deft lash to indicate shading, only an occasional charcoal line to assure shape potent fusion of two aesthetic thrusts: pure style and a peering into the soul. Dazzling technique is certainly the initial pull, but your gaze is held by a measure of the same subjectivity that underlies his photography. Ultimately, Dureau’s is an art freighted with emotion.

In the paintings, it should be stressed, there is a discernably unique tenor-something apart from that in the photographs. It has to do with discretion. A pervasive discretion. Dureau’s best paintings resolutely resist drama. They are supremely subtle, both in form and content. Formally, Elliot Lewis is like a poem about chromatic tact. It situates two warm hues in utterly close harmony, both muted and both constrained to middle tones -virtually free of contrast. The same is true of Ronnie Crawford. The only contrast here is a question of color temperature – the cool green of the background foliage versus Crawford’s coppery skin.

Both paintings imply a sensibility devoted to fluent lyricism, and this urges a treatment where small variations can be relished. You note, for example, a vague shift from the peach-tone of Lewis’s tank top to his slightly deeper complexion, then on to the still deeper background. All of these are analogous. Yes. But they are different hues, and each is broken into patch-like patterns-delicate adjustments of Dureau’s “insouciant” brush. And not much is made conspicuous – only an occasional deft lash to indicate shading, only an occasional charcoal line to assure shape and grace. This is a case of reined-in richness, but richness nonetheless. The result of such legerdemain, of course, is something quietly rapturous, like a lesson in refined taste. But, in fact, this surface beauty also contributes directly to Dureau’s core meaning.

The significant thing is this: In these works, the close harmonies and hushed visual incident create the perfect site for an incisive study of portrait subjects. And this study seems as care fully pondered as the technique. With this approach, Dureau seeks out subtleties of human presence, not the outsized emotions. The small, but telling, things are revealed. His tempered setting permits and encourages a closer look-something that high-contrast photographs might impede. Ultimately, the painted portraits are not human dramas; they appear, rather, to be musings on personality. They are attempts at tracing a particular disposition or humor or attitude. The utterance of such qualities looks like a natural for Dureau. The faces and poses here confirm it: Elliot Lewis’s intense, straining eyes, the near arrogance of his propped arm; the playful tilt of Ronnie Crawford’s head and, most notably, his affable glance. You can imagine distinct personalities.

Dureau, the artist of sovereign technique, employs that technique to ramify and deepen a message. It has to do with humanness.