by Jacquelyn Gleisner, via blog.art21.org

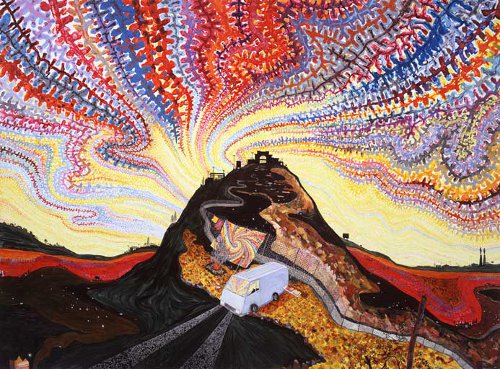

Lisa Sanditz. “Tie Dye in the Wilderness,” 2005. Oil on canvas. 57 x 77 in. Courtesy the artist.

The following interview took place via email on March 7, 2013.

Jacquelyn Gleisner: In recent years, your work has evolved from imaginative landscapes, high on a hippie/new age sensibility, to more recent depictions of factories and cityscapes. Brilliantly colored tie-dye skies have cleared and murky interior/urban landscapes have become more prominent in your paintings. Can you describe what prompted this shift?

Lisa Sanditz: None of the paintings are strictly imaginative. They are often exaggerated, pushing either a formal or narrative element, generally of a place I have visited or seen. The tie-dye painting for example, was my way of updating the epic technicolor skies of Hudson River School paintings, like Frederick Church’s Twilight in the Wilderness with a more modern psychedelic trope. I painted this after seeing an informal roadside tie-dye sales tent.

So the motivations have stayed the same, but the places I have visited have varied. In the industrial areas I visited in China in 2007 and 2009, the skies were often filled with heavy smog, which I thought of as a polluted extension of the fog often used in Chinese court paintings. Though skies were at times dim in China, the colors there were often saturated as well, with a booming consumer economy and a dizzying array of lights, shops and economic optimism.

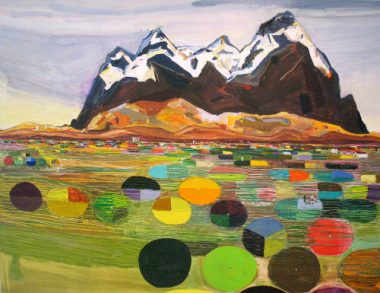

Lisa Sanditz. “Pizza Farms, ” 2011. Oil on canvas, 16 x 20 in. Courtesy the artist.

LS: The idea of branding as an artist has been around for hundreds of years, as you know. Artists had busy studios with many apprentices working diligently on the master’s pieces. Now, some artists work this way; others constantly shift directions. Both are viable.

I was particularly intrigued when visiting a factory where artists were painting copies of paintings from reproduction. I watched a young artist paint a reproduction of a Dali painting from a postcard, having never seen a Dali painting in life. It was quite impressive and a phenomenal collapsing of space and time. Wouldn’t Dali love that?

JG: You stated in a recent interview that you think the art world has changed since you shared a studio with a handful of other painters in Tribeca. How do you think things have changed? What new challenges do artists face?

LS: Actually, maybe I’ve changed more than it has. After September 11, I got a studio in Tribeca with friends from graduate school. Real estate was in a liminal time down there—and so was I. I was just finishing graduate school and having my first shows. My community of artists was broadening and still is. But now I spend most of my time upstate, working in my studio and teaching, so the art world for me is a quieter, more intimate one.

Ten years ago, it seemed there was a lot of money, and many people were selling everything off the walls. There is still a lot of money in the art world, despite a rancorous economy. For better or worse, it is still part of the conversation. There were trends in all disciplines of art making and those trends have been replaced by new ones. That cycle will continue.

Certainly, the Internet has connected and divided us. Ten years ago, we were just beginning to troll online. Shortly thereafter there seemed to be a bunch of blogs where people anonymously posted about work—brave and snarky statements comingled. They still exist, but Facebook’s dominance makes it a great billboard for events and fleeting thoughts, though the conversation is not as expansive there.

I show in commercial galleries and move within that world, but one thing I’d like to see change is the casual conversations that happen within it. Often at openings and events, the first question is, “When or where is your next show?” I’d like it to be, “What are you working on?” or “What are you reading?” or even “When did you last eat a great cheeseburger?”

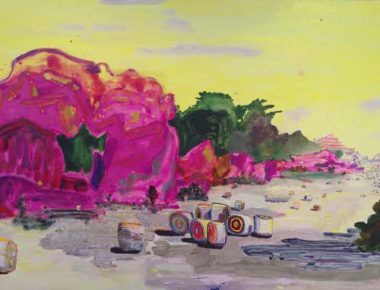

Lisa Sanditz. “Swamp Farm,” 2011. Acrylic and oil on canvas. 40 x 42 inch. Courtesy the artist.

JG: Things have changed yet you are still making highly expressive oil paintings. What do you think the artist’s role is in contemporary culture?

LS: Things keep changing, and there are new subjects to paint daily. A lot changed between Goya and Beckman and both were making highly expressive oil paintings. Wouldn’t we be deprived if neither did? There are many ways to communicate an event or a reaction to something private or public. Painting is the way that I can do it best. (And I don’t elevate myself to the artistic achievements of Goya or Beckman, with respect.)

Lisa Sanditz. “Hay Bales,” 2011. 30 x 40 in. Courtesy the artist.

What’s the artist’s role? Make art that gets you as the artist excited about the work. I get excited about it when the work is referencing ideas and situations outside of the art world.

JG: What’s next for you?

LS: Right now, I am making paintings about food and farming. I have also been working in ceramics since last summer. It’s a blast so far.

JG: Lastly, when’s the last time you had a really great cheeseburger?

LS: It’s been too long!