In the aftermath of the Japanese earthquake and tsunami, artists are creating works that document the event, give aid to the victims and express their own complex feelings.

This article originally appeared in the June issue of Art & Antiques Magazine as “Visualizing Disaster”.

More than a year after the massive earthquake and tsunami that hit the Tõhoku region of northeastern Japan, killing some 20,000 people and causing a nuclear radiation disaster, survivors are still struggling to make sense of what hit them and to rebuild their shattered lives.

The events of March 11, 2011, prompted reactions from artists in diverse fields both inside and outside Japan. Pop musicians, writers and filmmakers have staged events and created works with the express purpose of raising relief funds. Inevitably, visual artists responded to the events, not only in an effort to help the victims but also to express themselves creatively and to try to make sense of their own feelings in the wake of the disaster. Because of the nature of the subject matter, their responses are both publicly relevant and profoundly personal. Here are three of them.

A very direct, almost reportorial approach to the earthquake and its aftermath comes from an artist who is not Japanese. The painter Amer Kobaslija, who was born in Bosnia and fled his war-torn homeland for the United States in the 1990s, is married to a Japanese woman and has close ties to Japan through her family. He lives in New York and teaches art at a small college in Pennsylvania.

Kobaslija was startled when, on the day the disasters struck, he saw the television-news clips of the tsunami rolling inland from the coast, sweeping up houses, ships, shopping centers, office buildings, schools, farms, baseball fields and whole towns in an unstoppable super-tide of all-obliterating sludge. Recently, he recalled: “It was a different kind of devastation, but still it reminded me of the destruction from war that I had seen as a child. It was very disturbing, and I knew that people were suffering because of what had occurred.” Soon after March 11, accompanied by his father-in-law, Kobaslija made the first of several research trips to the Tõhoku region to take photographs, make sketches and observe firsthand the scope of the devastation. “The scene in the disaster zone after the earthquake and tsunami was post-apocalyptic,” he says. “As an artist, somehow I wanted to respond to this horrific event.”

Kobaslija’s reaction was instinctive. Right away he set out to paint what he had seen and, by focusing on the effects of the disasters in and around one small town, Kesennuma, to bear witness to a moment whose full impact will probably not be entirely understood for years to come. With a nod to the Japanese printmaker Hokusai, who created “One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji,” one of the 19th century’s most iconic series of images of Japan, Kobaslija has titled his still-evolving series of oil paintings made on sheets of copper or aluminum “One Hundred Views of Kesennuma.” A group of these new works was recently shown at George Adams Gallery in New York.

“My paintings offer a visible record of the effects of the disasters, but they’re not merely journalistic,” says Kobaslija. Indeed, insofar as most of his images are composites made from various photos and hand-drawn sketches, a certain interpretive function on the artist’s part has helped shape these pictures. They fall, however unexpectedly, into the category of landscapes, even though their subject matter is more phantasmagoric than idyllic and not what many viewers would expect to encounter as examples of this genre. They might also be regarded as a form of contemporary history painting, vividly recording for posterity an era-defining event. The painter says: “I’m trying to give you a sense of what it feels like to stand on a hill, looking out across a landscape of destruction. I want to commemorate what was lost but also say to the victims and survivors, ‘Your painful experience will not be forgotten.’ Art can serve a purpose, to help us remember.”

Technically, Kobaslija’s images are notable for the luminosity of their oil paint. It rests on each picture’s metal surface and calls attention, on close inspection, to the size, thickness and character of each brushstroke. Despite their many brushy passages that are as fluid as those of more free-wheeling, abstract expressionist tableaux, Kobaslija’s pictures offer a remarkable sense of wide-angle detail but are by no means photo-realist works. Instead, their technical tour de force is filtered through the painter’s understanding of what he witnessed in person, along with his own signature effects. For example, Kobaslija’s exaggerated, multiple perspectives have been evident in his art for many years; they turn up in the claustrophobic views of his various studios that he painted in the past. They are visible here again in rollicking land forms and elastic skies filled with billowing clouds of smoke.

“I could not believe my eyes when I saw the TV news and then, in person, when I saw the disaster zone,” recalls the Japanese-born artist Naoto Nakagawa, 68, who came to New York on a student’s research fellowship in the 1960s and settled there. Today, he shows his work at Feature, Inc., in Manhattan. His body of work to date has been diverse, including realistically rendered, complex still lifes featuring lawn mowers, bicycles, ice skates and unusual objects, and various series of paintings (in a range of different media, such as sumi ink) focusing on flowers, trees and nature. Recently, at his downtown studio, Nakagawa said, “I contributed to Japan-relief funds but I still felt powerless about helping the disaster victims. I wanted to do something more direct, more personal.”

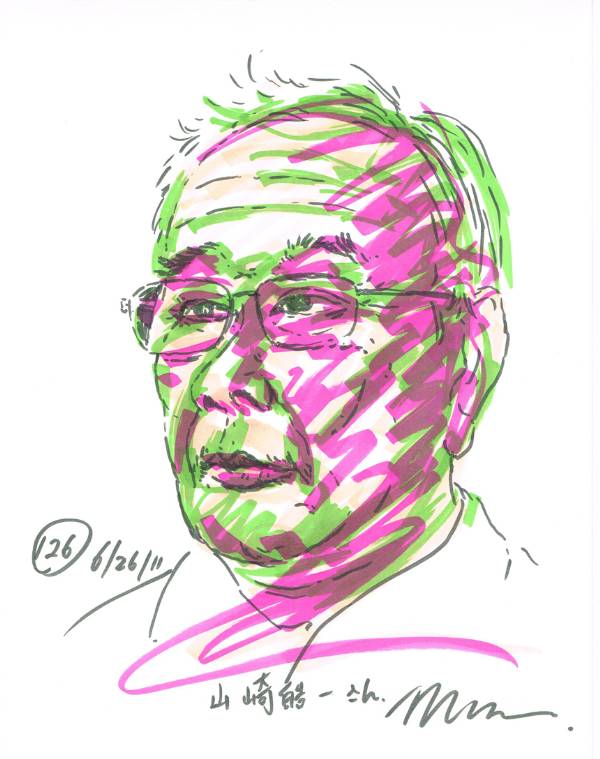

Two months after the earthquake and tsunami, he traveled with his teenage son to Japan and headed to Tõhoku. There, at an evacuation center in the town of Õtsuchi, in Iwate Prefecture, Nakagawa sat down and began drawing portraits of men, women and children in the shelter whom the disasters had left homeless. His goal is to make 1,000 such pictures. Nakagawa’s sitters posed for him while he quickly drew their likenesses using only brush-nibbed, felt-tip markers on thick sheets of white paper. Since then, the artist has made subsequent working visits to Japan. He has promised his sitters that he will give them their portraits in the future.

First, though, Nakagawa has been showing batches of images in what he is calling his “1,000 Portraits of Hope” series to well-known figures in business, politics and the arts in the U.S. and Japan, and inviting them to also sit for portraits. These pictures of individuals with some measure of celebrity will be auctioned off to raise money to help fund relief efforts in the disaster-affected region. Nakagawa says: “I’d like to see whatever funds this art project can raise go toward the construction of much-needed recreational facilities for the people who lost everything—sports clubs, cultural centers, movie theaters. Many of the homeless have spent many months in evacuation centers, living in anxiety. They’re scared and depressed.”

A selection of images from Nakagawa’s “1,000 Portraits of Hope” series was recently shown at the Sidney Mishkin Gallery at Baruch College in New York, alongside photographs of the disaster-hit region by Magdalena Solé, a New York-based, Argentine-born photographer. Through August 5, Nakagawa’s portraits and Solé’s photos are being featured, along with poems penned by displaced Tõhoku residents, and rescued and restored family photos, which had been damaged by the tsunami’s muddy assault, in “Voices from Japan: Despair and Hope from Disaster,” an exhibition at Manhattan’s Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine.

In Japan, Hiroyuki Doi produces abstract drawings made with felt-tip pens on Japanese washi paper. A retired master chef who specialized in European cuisine and worked at top hotel restaurants in Tokyo, Doi, 66, began making art after the death of his younger brother many years ago. Consisting of countless tiny circles amassed in free-form compositions resembling fluffy clouds, churning whirlpools or observatory-telescope photos of distant galaxies, Doi’s works have alluded, the artist has said, to such themes as “the transmigration of the soul, the cosmos, the coexistence of living creatures, human cells, human dialogue and peace.”

“I did not want to be defeated by the earthquake; it was such a difficult time for us Japanese people,” the Tokyo-based artist recalled during a recent visit to New York, where he shows his drawings at Ricco/Maresca. As a result, he explained, two months after the disasters struck, he began making what would turn out to be—at more than six feet in length—his largest work to date. Titled Hope for the Earth, the big drawing took Doi four months to create. Its sprawling composition, he says, symbolizes a mother’s enclosing womb, the forces of the universe protecting the Earth and even a nuclear reactor.

“This work is my way of expressing my condolences to all of the people who lost their lives in the disasters,” Doi says. “It commemorates all of their souls.” Unlike Kobaslija and Nakagawa’s essentially realistic images, Doi’s work uses the visual language of abstraction to honor the dead and express a sense of aspiration for the future. Doi has employed the ambiguity of abstraction to communicate a bundle of complex, free-floating emotions.

As if their physical-survival concerns were not enough, the displaced people in the disaster-affected region who came from the area contaminated by radiation from the damaged power plant could encounter another challenge. At a recent symposium at Columbia University in New York, which examined the mental health of Tõhoku’s displaced residents, Columbia radiation biophysics professor David Brenner noted that people from the area around the Fukushima Daiichi plant now face “radiation stigmatization.” To be identified as coming from that area, he said, “has become a mark of disgrace.”

In calling attention to the still-reverberating impacts of last year’s Japan disasters—or at least by suggesting, “Let’s not forget them”—Kobaslija, Nakagawa and Doi have used their art to commemorate the victims of the earthquake and tsunami, and to honor the indomitable spirit of the catastrophes’ survivors in the face of numerous hardships. “I threw myself completely into the creation of my drawing,” Doi said. Similarly, Kobaslija and Nakagawa have emphasized that their Japan-themed projects are not dabblers’ pursuits on the margins of their main art-making activities, but rather central, full-fledged bodies of work within their respective oeuvres.