by Steel Stillman, via artinamericamagazine.com

The painter Wayne Gonzales messes with our expectations. He cracks open images we think we already know and injects them with subversive sensuality and doubt. Born in New Orleans in 1957, and growing up there in the ’60s, when rumors surrounding the JFK assassination hung thick in the air, Gonzales developed a sensitivity to secrets and coincidence. “Conspiracy” is not a word that Gonzales uses, but its etymology, in suggesting a kind of breathing together, evokes an atmosphere of nuanced interrelatedness that pervades his varied body of work.

The painter Wayne Gonzales messes with our expectations. He cracks open images we think we already know and injects them with subversive sensuality and doubt. Born in New Orleans in 1957, and growing up there in the ’60s, when rumors surrounding the JFK assassination hung thick in the air, Gonzales developed a sensitivity to secrets and coincidence. “Conspiracy” is not a word that Gonzales uses, but its etymology, in suggesting a kind of breathing together, evokes an atmosphere of nuanced interrelatedness that pervades his varied body of work.

Since his arrival in New York in the late 1980s, Gonzales has found inspiration in photographs and other documents that record the events of the past 50 years. His work is American not just in subject but in sensibility. Like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, Gonzales makes paintings that are both skeptical and romantic. Then he turns up the pressure, pushing the optical into the psychological: historical figures are individualized; corporate and political power is brought down to human scale; and viewers are invited to free-associate in an image-world that is both familiar and strange.

Though Gonzales protested against the Bush administration’s Iraq policy, he doesn’t describe himself as a political artist except to say that “all art is political.” In 2007 he collaborated with the poet Vincent Katz on a book project, Judge, in which a poem by Katz-a biting response to the Senate confirmation hearings of John Roberts for the Supreme Court-was juxtaposed with Gonzales’s images.

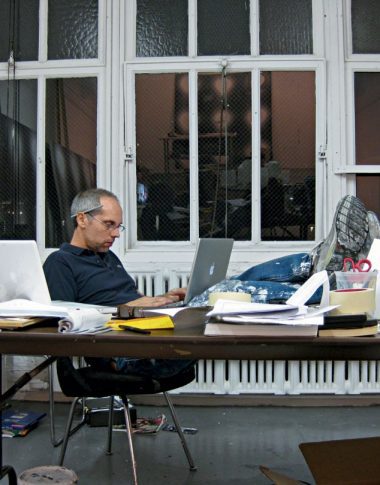

Since 1997 Gonzales has had more than 20 solo shows and has participated in dozens of group exhibitions throughout the U.S., Europe and Asia. He has taught at Hunter College and Cooper Union. Gonzales’s studio, high above Chelsea, used to have a great view of the Hudson River until a new condo tower blocked it; fortunately, he works best at night. The following conversation took place over the course of several days in early October as Gonzales prepared for a solo exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York. Another show of his work opens Mar. 18, 2010, at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London.

STEEL STILLMAN What was New Orleans like when you were growing up?

WAYNE GONZALES “New Orleans” meant the French Quarter to me, and I found it fascinating. The Quarter was like a continuous movie, full of nefarious and colorful characters. I loved it. Living in New Orleans also meant evacuating whenever a hurricane threatened-sometimes several times in the same year-so I grew up with a healthy sense of impending disaster.

SS What kind of work did your parents do?

WG My father was a beer salesman, and my mother was a payroll clerk at the New Orleans Museum of Art. The TV was on a lot at our house when I was a kid, but I didn’t like it and so

I would escape by making drawings.

SS What would you draw?

WG I had a James Bond 007 Electric Drawing Set, which included a plastic light table and a “portfolio of 007 adventures”-drawing templates of a comic-book Bond in various poses and an assortment of enemy agents. I would trace them to improvise my own characters. Recently I bought a set on eBay, and when it arrived, it was funny to see that my portraits of Jack Ruby and Oswald are direct descendants of the enemy agents.

SS I’ve read that you grew up on the street where Oswald was born.

WG We were born on the same street-of course, we didn’t overlap-and my family moved to the suburbs when I was two. But my family had other connections to the JFK story. A friend of my parents was a key investigator for New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison who was investigating various conspiracy leads. And the local mob boss, a suspected conspirator who had a personal beef with the Kennedys, was related to my mother by marriage. My father worked in the Quarter, so when Garrison went public with his investigation, I already knew a lot of the names and places. My father was very street-smart and had noticed Oswald hanging around the Quarter. When I was nine or ten, I wasn’t as interested in who killed Kennedy as much as I was fascinated by the structure of the Garrison investigation, and how it related to my understanding of my hometown. Regarding the investigation, I realized that if you put a group of people together, you could make a certain kind of sense; but, if you replaced one person with somebody else, it would make sense in a very different way. I discovered on my own that history is a construction, and that there are always alternative versions.

SS When did you decide to become an artist?

WG I knew when I was a child that I wanted to be an artist, but didn’t know what that meant. As a young adult, I left college twice and worked as a commercial artist for a few years before going back to school to study fine art. When I graduated in 1985, I was 28. Then I tried graduate school in New Orleans for a year, but didn’t feel challenged enough. In 1988 I moved to New York.

SS What did you do when you got to New York?

WG I worked as a word processor at first and then got a job as a studio assistant for Peter Halley. Working for Peter was like going to graduate school but better. It was stimulating, and I met other artists, as well as writers, curators and dealers. I lived in a small loft on the Lower East Side, and after work I’d go home and paint all night.

SS What kind of art thoughts were you having?

WG The Warhol retrospective at MoMA in 1989 made a huge impression on me. Seeing large amounts of his work helped me to understand, in a way that I hadn’t before, how his use of the silkscreen could be painting. I began making silkscreens myself, working intuitively, using the screens as templates-mixing them up, moving them around, working serially, changing colors. They allowed me to take an image apart and reconstruct it in ways that wouldn’t have occurred to me otherwise.

SS So using silkscreens allowed you to work more abstractly?

WG I never had a conventional painter’s training or “hand,” so using a given image as a template allowed me to engage materials, space and ambiguity without having to worry about virtuosity.

WG I never had a conventional painter’s training or “hand,” so using a given image as a template allowed me to engage materials, space and ambiguity without having to worry about virtuosity.

And then, in the early ’90s, I began working on the computer in the same way, using an early version of Photoshop. I worked first in portraiture, distorting and scrambling generic faces and painting them on canvas using hand-cut stencils and a sprayer. Again I worked serially, using the same image on a number of canvases, but modifying it slightly from one to the next. Some of these were in a 1995 two-person show at Lauren Wittels Gallery in New York. [Gonzales married Wittels in 1997.]

SS Your first one-person show at Lauren’s two years later had a greater range of subject matter.

WG That work also came from drawings I had made on the computer. There were portraits, landscapes, buildings and abstractions. I had a vague notion that my first one-person show should look like a group show. That idea related to things I was reading about multinational corporations-about their way of gathering diverse businesses into a single corporate entity with the power to influence politics and culture. At the same time, I’d begun collecting material related to the JFK assassination, and that became my other organizational model. The show consisted of seven stylistically disparate paintings in varying degrees of representation and abstraction that I hoped would relate to each other in some larger abstract way.

SS What led you to take on the assassination more explicitly in the 2001 show at Paula Cooper?

WG I hadn’t planned to make work about the JFK material. But around 2000 my growing collection of assassination-related images had become more interesting than the other source material I’d collected for painting. At some point I began printing JFK images and painting over them with gouache. A million ideas came pouring out. I was making 20 or more drawings every couple of days and putting them in a box. I didn’t see it as art-making: it just felt like energy flowing.

Sometime later, I showed the drawings to the writer and curator Bob Nickas, and he asked if I would make a painting based on one of the drawings of Jack Ruby-a green one-for a show he was curating at Team Gallery. He said, “It’s got to be big!” So I bought huge stretchers and struggled to paint this big green picture of Jack Ruby. At the opening everyone standing next to it looked green.

Soon after, the artist Dan Walsh put me in a group show he was organizing at Paula’s, and I was invited to join the gallery. My first show was scheduled for the main space, which is essentially a 50-foot cube. I’d always thought of that space as larger than life, and it seemed important to address the scale of the architecture with my work. The JFK stuff seemed big enough to do that.

SS What was in that show?

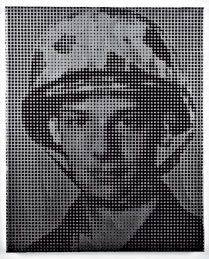

WG There were nine paintings, each based on a documented fact or theory-“evidence”-related to one of the investigations. Among them was a painting of Kennedy’s head exploding, based on a frame from the Zapruder film, a representation that is both factual and abstract. I cropped it as though it were a Warhol portrait of Jackie. That was juxtaposed with paintings of diagrams illustrating possible bullet trajectories. There was also a painting of the mysterious “three tramps,” who were seen only in photographs taken at the scene. There was a stripper in Jack Ruby’s nightclub and a pair of paintings of Oswald himself. Another painting was based on a photo of Oswald wearing a helmet as a young Marine. I replaced Oswald’s face with my own high school yearbook portrait.

SS History provides a readymade template for the JFK paintings, not just for you as the painter but for the viewer as well. Similarly, visual references-especially to Warhol-seemed like improvisations on the history of Pop art.

WG Pop art is, for me, partly about the dissemination of images-and once I started working on the computer I realized that I was more interested in the manipulation of images. For the JFK paintings I was responding subjectively to the technology that had produced their source images, and the methodology I used for each painting reflects that. My overall goal for the exhibition was to create a mood, a psychologically charged space between the paintings. But at some point as I worked on them, I realized that every painting related in some way to the visual strategies of Pop and, specifically, to Warhol. It bothered me a little at first, but then I embraced it and played it up.

SS The manipulation of Oswald’s eyes in the large peach-colored portrait seems to humanize him.

WG The idea to alter his eyes was a simple pun on the phrase “head shot,” a reference to an actor’s head shot but also to the bullet to Kennedy’s head. I made the painting really large so that the eyes would be at the same height as the viewer’s. At the risk of sounding corny, the eyes were also intended as a knowing gesture-Oswald was the only person we can be sure knew whether he’d done it or not.

SS And then you go further in the Marine paintings, blurring the boundary between yourself and Oswald, turning his image into a self-portrait.

WG The self-portraits came late in that body of work. I began to see Oswald as a stand-in for the artist and to identify with him, not so much as a person but as a construction, as someone whose history was fabricated by others, and as an individual in relation to larger events and interpretations.

SS After the JFK series, your sensitivity to hidden networks of power and influence picked up fresh signals in contemporary life. You even began using a computerized plotter to cut stencils, in your studio. Did current events take over?

WG It was taking me a month or more to make a painting, and I was getting frustrated. Under each finished painting there seemed to be as many as 10 other paintings, three or four of which might have worked just as well. And then 9/11 happened-it happened just before the JFK show opened-and suddenly life seemed too short to spend a month on one painting. Buying a plotter helped with that.

In New York, I live close enough to the [World Trade Center] site that I could smell it, and I had been used to seeing the towers. Consequently, my childhood memories of having to leave home in a boat resurfaced, and one day on Hudson Street I found myself visualizing all the buildings as rubble. With the JFK stuff and then the 2000 presidential election, I’d already been thinking about power in relation to the individual. With 9/11 and the impending invasion of Iraq, those thoughts became more urgent.

In response, I started making paintings of the White House and of an aerial view of the Pentagon looking like a ruin. I began to think of images as maps, constructed in layers that were modeled on the four-color process, but reconceived as monochromes. I deliberately left the resolution coarse so that the image was accessible from across a room but vanished as you approached. It was a simple metaphor for how little access I felt we had to truth during the Bush administration. Meanwhile I had the catalogue Picasso and the War Years: 1937-1945 lying around the studio and was thinking about how somber his palette became during that period.

SS The real estate paintings that you began making in 2004 show luxurious houses and condominiums and resort hotels in dramatic landscape settings.

WG With the real estate paintings, access to power became access to resources-a real estate boom was raging while I worked on them-and to nature. For years I’d wanted to do a landscape painting, but didn’t know how to approach it. I felt too invested in culture. But once I put a house in front of a mountain, it worked.

SS These paintings combined banality with something sinister. The fact that one painting was of a resort in Berchtesgaden, near Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest retreat, reinforced that impression.

WG A friend had given me that image pretty late in the process, because what I was doing triggered those associations for him. But when I began the series, I’d been thinking about real estate development in relation to a spatial problem I wanted to solve using color theory. In smaller studies, the green and yellow palette seemed strong but not overwhelming. But when the paintings got large, the color became more abrasive, more a part of the content. We were installing them for a show in New York, and everybody there was talking about how toxic it all looked, when two young Japanese gallery interns came in and said, “Oh! Spring! How beautiful!”

SS How did the crowd paintings come about?

WG After doing the real estate pictures, I wanted to paint something by hand, so I began experimenting with a crowd image that I’d first painted with stencils several years earlier, when I’d been going to antiwar protests. I took the image apart the way I had with the real estate paintings, and projected and hand-painted the parts independently. From afar the crowd cohered as an image, but up close the faces began to decompose into pure gesture. The marks became stand-ins for physical contact, and the whole mood seemed interestingly opposed to the White House pictures. From there, I explored how crowd images are event-specific, and how that perception changes if I erase all evidence of their context.

SS Though the source images for the crowd paintings are rarely of political events-many are from sporting events, one is from an air show, and the most recent ones show people at the beach-they nonetheless conjure a range of associations: from feelings of vulnerability, excitement and anticipation, to thoughts about democracy and the role of surveillance in contemporary society. And in representing audiences that sometimes look in our direction, these images relate directly to us.

WG They played off my feelings of alienation at the time of the Iraq war protests. I was thinking specifically about how empowered and emboldened one can feel in a crowd, and then feel depleted upon leaving. And I was intrigued by how scale was being used ideologically. During the protests, estimating the size of the crowds, over- or underestimating depending on which side you were on, became a point of contention.

SS What is the source for the most recent light paintings?

WG They are based on a photograph of the sun that I shot from a plane sometime in the late ’90s. The idea of taking this one image and repeating it to make a grid of spotlightlike suns came a bit later. Partly, it was in response to New York being turned into a movie set-to the creepy feeling of turning a corner at night, running into a TV or film shoot and having it suddenly be day, thanks to a bank of floodlights. The first “light” paintings were done in 2004, but it seemed a good idea to revisit the subject now. I’ve been doing figurative paintings for the last few years, and my palette keeps getting darker. So, I’ve started thinking about light.

SS Though they suggest stadium lights, they also evoke something post-apocalyptic; there’s a lot of darkness in them.

WG I’m looking for an ethereal mood more than anything else. I want them not so much to shine on you as to draw you in.

SS Beginning with the White House and Pentagon paintings-and increasingly with the subsequent real estate, crowd and light paintings-your various series feel connected.

WG I see them all as parts of the same whole. In the way they are constructed, the real estate paintings build on the White House paintings and the crowds build on the real estate paintings. But then I’ve exhibited the crowd and the light paintings with the White Houses, too. I like to investigate things in depth and then move on, but sometimes I find myself circling back. For the past few years, most of my source material has come from the Internet. Being able to access and download hundreds of images in one sitting has meant that many different things can become active at the same time. I can’t always tell where these images will lead, if anywhere, and some may only make sense later.

SS Because your work is full of identifiable imagery, it can be tempting to read it in narrative terms, to start connecting dots.

WG My sense of narrative is non-linear and abstract, and has to do with simultaneity. When I step back and take a long view, I can see an overall clarity of purpose and how things might interrelate. However, my work develops out of intensely subjective impulses, and when I am working I am definitely not trying to “make sense.” The goal is to turn those impulses into a blank screen for the viewer.

SS Do you remember where you were when Kennedy was shot?

WG I was in first grade. We were sitting at our desks preparing to take a test when the live newscast came over the loudspeaker. I don’t remember what my reaction to the event was, but I remember that the bell rang, and as we were leaving the classroom, I passed by the teacher’s desk and noticed her copy of the test sheet, and it was completely black. She had compulsively doodled over the whole thing.